At the end of an interview with Jonathan Rosen conducted in 1994, V.S. Naipual says, "Do you think I've wasted a bit of myself talking to you?" Rosen hedges, saying that’s not how he’d put it. Naipaul says, “You’ll cherish it?” It is nasty and ungracious. It is also true. And this—the willingness to say something awful and true—is the reason why I want to hear Naipaul describe the world. He is more honest than most of us dare to be.

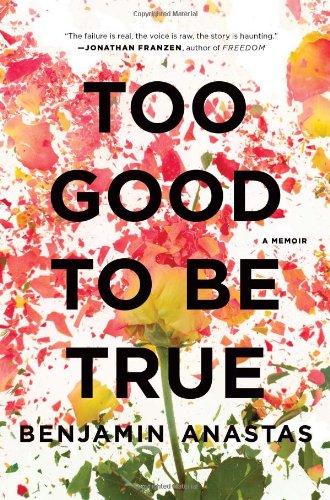

In Benjamin Anastas’s Too Good to Be True—a memoir that should be required reading for all creative writing MFA candidates and, come to think of it, anybody who is engaged to be married—the author tells the story of his failure. The word is used by Anastas himself, and while I wouldn’t use it to describe his work, it does capture the raw honesty that powers this book and renders it a success.

In 1998, when Anastas was twenty-nine years old, Dial published his first novel, An Underachiever’s Diary. (This was when Dial was run by the peerless Susan Kamil.) Diary was not a runaway success, but it was touched by a certain magic. People began to recognize Anastas on the streets of New York, where he lives. But this was not necessarily a sign of good things to come. FSG published the author’s second novel, The Faithful Account of a Pastor’s Disappearance, in 2001. He writes, “There are secrets in publishing that no one ever tells you when you are young. Most books die at their first printing. That’s the biggest one… I wrote a book. The world yawned.”

Anastas married and wrote his third novel in Italy, refusing to submit to his writer’s block. He wrote through it, and the resulting book did not do well at the Frankfurt Book Fair—it sold to a minor Austrian publisher for an amount too small to mention. No U.S. publisher bought it. We can guess that he took the offer from the Austrian publishing house because he desperately needed the money: money troubles are a constant demon in this book. Anastas tells us that he has borrowed money from friends and family and even—God knows how—from an attorney he met at a bar.

The night Anastas got the news about his third novel, he slept with a beautiful woman from an Italian publishing company. Soon after, his wife had her own affair, and—pregnant with Anastas’s son—left Anastas for another writer.

This is the backdrop for his sad memoir. Too Good to Be True is written from the perspective of the present day, as Anastas sits in an apartment in Brooklyn with his office door locked. He’s decided to stop writing on computers—the ability to delete and rewrite affords him too much opportunity to enamel the life out of his own work. He’s writing in notebooks. He says he no longer has the patience to put a veneer of fiction over the situation. He is forty-two, his girlfriend Eliza is thirty-eight and wants a stable life. Bill-collectors call Anastas at midnight and interrupt him reading Thomas Merton to her in bed. “Who would call at this hour?” she asks him (he knows better than to answer). He is seeing a psychic healer. He prays. He collects change and hauls it to the Coinstar before the weekend visits with his son: these visits, and Eliza, are the only light in his increasingly dark, frightening life.

Anastas had a normal childhood. By that, I mean that it was one of rococo lunacy. His mother and father were hippies. His father had a bushy beard and a tan so dark a stranger in a passing car flashed him the Black Power fist. He drove a VW bug with no A/C, a single functioning seatbelt (the driver’s), and a maximum highway driving speed of 53 miles an hour. When a sedan passed him on the freeway he said, “There go Mr. and Mrs. America.” Young Anastas, hair uncut, wearing sandals and hand-made clothes embroidered with starfish and rainbows, pressed his face to the window and said, “Where?” It was his father’s running joke to moon friends; he would bend over, pull his underwear down, and spread his cheeks in the A&P parking lot.

Anastas’s mother was depressive. When her depression became insuperable and another trip to the mental hospital might cause the state to take her children away, she checked herself and her children into an experimental treatment program called “Freedom to Be.” The goal of Freedom to Be—which was modeled after drug-treatment facilities—was to dismantle the so-called personalities of its patients, allowing them to be who they really were, whatever that was. Care-givers watched Anastas and his siblings play. They formed impressions. Young Anastas, it was noted, pretended to be more virtuous than he really was. He played the good little boy, the hero. So they put a sign around his neck that said, “Too Good to be True.” I mean, literally.

Anastas’s hopes lie with Eliza and his son. Eliza leaves him because she wants curtains instead of blinds, and a bed frame, not a mattress on iron casters. Anastas doesn’t have enough money to support a marriage, or even its beginning—an engagement ring (portentously, Eliza had chosen a black diamond). Their break-up is a painful scene. She asks Anastas what his financial situation is. He says, “I’m broke.” She says, “That part I know.” He goes to the shoulder bag in the hall where he keeps his collection notices, unpaid bills, and threats. He puts them on the counter. “Wait, there’s more.” He gets the “parking tickets, bills from doctors and hospitals,” and unopened phone bills from his sock drawer and puts those on the pile, too.

What distinguishes this memoir is Anastas’s willingness to expose his anger. The earnest men and women at Freedom to Be who watched the boy stack blocks and color pictures will be pleased. Anastas is angry with his first wife, and he is angry with the man for whom she left him. He does not kow-tow to the convention of casting oneself as the villain. He gives us something fresher: the contents of the shoulder bag’s inner pocket. I mean he gives us his side of the story, rather than an account that would make a Columbia English professor check the margin and scrawl, “Balanced.” Is it possible I have empathized with the wrong team—with the earnest hippies and their ideas? With Anastas’s scorching recollections? Maybe so, but just as I like it when Naipaul belittles his interviewer, I like it when Anastas puts his anger and worst impulses on the page. It has the ring of truth.

Amie Barodale is a student at the Iowa Writers Workshop and won the Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize in 2012.