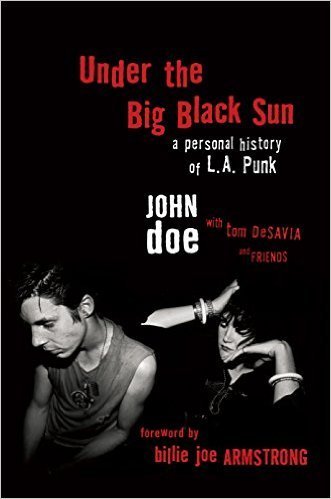

In Los Angeles in the middle of the 1970s several hundred diverse misfits came together and began to collaborate. Some were high school glam-rock enthusiasts, like Belinda Carlisle, Jane Wiedlin, or the boys who became Pat Smear and Darby Crash. Others were older, having traveled farther. From Baltimore came John Doe, from Florida came Exene Cervenka; in California they met and fell in love. Together, and against the world, these few hundred sparked an experiment called LA punk rock—an impulse, some might say, a happening, an underground movement, a rebellion, a cultural revolution. Mention of it now usually stirs memories of mohican haircuts and hardcore music, stage-diving and slam-dancing, but those didn’t come until later. There was an initial punk endeavor in the city that was far different. The charismatic Tomata du Plenty at the front of The Screamers. The wonderfully harebrained choreography of Devo, newly arrived from Ohio. Photographers, cartoonists, poets, painters, and performance artists participated fully, supporting and contributing to a movement that was all about risk, immediacy, rule-breaking, and anti-materialism. Despite how that sounds, the scene was a welcoming one, more Brando and Bettie Page than what was going on in New York and London at the time. This is the moment with which John Doe’s new book Under the Big Black Sun concerns itself, shining a light on a legendary but largely unexamined corner of the West Coast counterculture.

This LA moment ran from 1976 through 1981, and Doe, a founder of the band X, saw much of it firsthand. Under the Big Black Sun—which Doe wrote with Tom DeSavia and includes contributions by a number of others musicians—gathers together a few of the musical and critical celebrities, allotting them each a chapter or, in the case of John Doe, several chapters. Here nostalgic fans of LA punk will learn amazing things: how The Go-Gos and The Germs grew out of the same rehearsal space, how the stories of Charles Bukowski inspired not only the lyrics but the lifestyle of X (the cigarettes, tattoos, and booze), how friends became bandmates, parties went on for weeks, everyone was high and no one had any money, and some people died, and some became famous, how the scene was pansexual, gay-friendly. There was a Saturday night radio show on KROQ and another very early in the morning on KPFK. There was a magazine called Slash that everybody wrote for and everybody read. Shows were frequent, advertising was word-of-mouth, and the music industry took little note.

One difficulty with heralding LA’s early punk scene has traditionally been the lack of evidence. Few if any of the surviving recordings can convey the audacity or vitality of what was said to be happening in the city during the late-’70s. The compilations and 45s from then sound as if they were mastered on sheetrock. Meanwhile, New York had Patti Smith, The Ramones, Talking Heads, Television, Blondie; London had The Clash, The Damned, and the Sex Pistols. Each of these young acts produced an immortal disc before the whole of Los Angeles managed its first, X’s debut, Los Angeles, produced (in a lovely passing of the torch) by ex-Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek. And yet, as people who got the chance to witness bands such as The Zeros, The Screamers, or The Bags will tell you, LA’s scene during its pre-1980 invisible years was unsurpassed.

Alas, this book is not convincing on this point. Many of the major players from then describe what they recall of those days, but in the end it’s too much about drugs, drinking, and dress. There are too few reproductions of photos or drawings or reviews, nor are there any attempts to reconcile conflicting chronologies or to establish an authoritative account. While this makes Under the Big Black Sun appear appropriately collaborative and anarchic, the book’s meandering, and its refusal to provide much in the way of penetrating cultural analysis, does little to justify or distinguish LA’s punk moment. The value of this book lies not in its arguments but in the details and data that will nourish future biographers and delight the production designers of the inevitable biopics.

Thankfully one can now survey the pages of Slash Magazine, to be published as a book later this spring by Hat & Beard Press (Slash: A History of the Legendary LA Punk Magazine), to confirm reports of ephemeral LA inventiveness that went otherwise undocumented. Among the smudged newsprint of Slash are the comics of Gary Panter, the rants of Richard Meltzer, the photographs of Melanie Nissen, and interviews with forgotten pop anarchists of the period.

It began in May 1977 this way: “So there will be no objective reviewing in these pages and definitely no unnecessary dwelling upon the bastards who’ve been boring the living shit out of us for years with their concept albums, their cosmic discoveries and their pseudo-philosophical inanities.” The coeditor of Slash was Claude Bessy, in whose writing one heard the full voice of the LA punk experiment, outraged and brilliant, writing as if his life depended on it. Perhaps it did. Bessy died some years back and with him went the explanations and justifications, the overarching philosophies and aesthetics which, though lacking in Under the Big Black Sun, seem necessary to appreciate what was then unique about southern California.

It went fast.

In late 1980, a number of things happened at once. Claude Bessy left the country and Slash magazine folded, leaving readers with the most provocative communiqué a dying periodical could ever muster. “Just because we won’t be on your back for some time does not mean you ought to take it easy, get all passive drinking beer on the back porch letting the surrounding mellowness get to you. The time is crucial, you don’t have that much longer.”

X found acclaim with a great debut, lead singer Darby Crash of The Germs killed himself, and the documentary film about LA punk The Decline of Western Civilization was released.

True to its name, the film signaled the end of an era.

After The Decline… everything was different. The music’s popularity exploded, its character radically changed. In one of the later chapter of Under the Big Black Sun, Henry Rollins (of Black Flag) reports how he arrived from Washington DC to find a nihilistic LA scene passionate about destruction and aggressively amoral. It had completely lost its sense of humor, its sense of purpose. Heroin was big. So was rape.

Another of the book’s contributors, Mike Watt (of The Minutemen), writes how the very movement that’d encouraged weirdos like himself and Minutemen singer d. boon was soon overtaken by judgmental jarheads and shaven-headed jocks who worked to turn each gig into a mob as imagined by Nathanael West and didn’t seem satisfied until the police got their helicopters involved.

This is the pathetic vision of punk that remains, the fashion cliche that LA punk became after Darby’s death, after young white suburban males flocked by the thousands to the city, drawn by local TV news stories of “ultraviolence.”

Under the Big Black Sun goes some distance in attempting to undermine that cliche, to shade that vision with nuance and personality, but it doesn’t go nearly far (or deep) enough.

Camden Joy lives in New Jersey. His collection Lost Joy was recently republished by Verse Chorus Press.