Japanese Noh theater would seem to be an odd subject for William T. Vollmann, were it not for the fact that nothing human is alien to him. Indeed, he is one of the very few writers among us about whom the latter statement can be made without irony. His appetite for all human behavior is so truly omnivorous that the book’s subtitle—Beauty, Understatement and Femininity in Japanese Noh Theater, with some thoughts on Muses (especially Helga Testorf), Transgender Women, Kabuki Goddesses, Porn Queens, Poets, Housewives, Makeup Artists, Geishas, Valkyries and Venus Figurines—is not an exaggeration.

Vollmann, who since 1987 has published approximately twenty volumes (some more massive than this one), has a well-established practice of exhausting his subjects through voluminous research, and also of identifying with his subjects by repeating the experiences being portrayed—even in the most difficult and unlikely cases. He is the author of several impressive historical novels (The Ice Shirt, Fathers and Crows, The Rifles, Argall, and the National Book Award winner Europe Central) involving experiences that, absent a fully functioning time machine, would seem impossible to repeat, but still he tries, sincerely and energetically. To improve his understanding of the doomed Franklin Expedition, on which his novel The Rifles is based, he spent two weeks camping alone in profoundly sub-zero temperatures at the Magnetic North Pole, and practically everything else he has written has required similar experimentation on his own person. The amount of book-learning required for his projects means that his armchair time must be considerable, yet at the same time he is a highly intrepid world traveler, who has flirted intensely with the most addictive drugs so far invented, embraced the most hazardous sexual adventures available to him, been wounded in the war zones of the Balkans, and courted violence in all its forms for his encyclopedia on that subject, Rising Up and Rising Down.

By comparison to all that, Noh theater seems rather a delicate topic, and yet it might really be as challenging to penetrate the inner world of Noh as to survive winter conditions at the North Pole. Vollmann, nothing if not persistent, succeeds very well in working his way backstage. His interviews with several present-day Noh performers and carvers of masks are buttressed by readings of Japanese novelists like Yukio Mishima, who reworked several Noh plays in his fiction, and of the fourteenth century performer and playwright Zeami, whose aesthetic treatise on Noh still governs the genre today. Vollmann, protesting that his understanding of Noh is shallow, disclaims that his work is a handbook on the subject. However, in view of the probability that his average reader will know next to nothing about it at all, he does provide a very effective introduction to Noh, both as performance and as text. Especially for outsiders to Japanese culture, Noh theatre is a difficult taste to acquire; enthusiasts of Vollmann’s previous work may be more interested in why he is so determined to acquire it.

In one sense, to write a deep study of beauty and grace balances Vollmann’s vast body of work about violence; in another, the mannered, conservative world of Noh players and geishas fits well at the opposite end of the spectrum from his long-term involvement in the culture of street prostitutes all over the world. The essence of the feminine is part of what attracts him, but in this new book that idea rubs up against “the possible genderlessness of the soul, whose most appropriate reification might be that ancient Hungarian figurine whose shape was of an erection with testicles but whose glans was a woman’s face and whose long neck bore hard-nippled little breasts almost halfway down; the scrotum was a woman’s buttocks.”

If the soul should be genderless, then femininity must be performance: an idea to which all phases of this wide-ranging book returns. Vollmann, whose haplessly blunt interview technique is unexpectedly disarming, approaches three women (American, Japanese, Serbian) with three questions: “What is your soul? Who are you as a person? Who or what are you as a female body?” The strikingly candid replies indicate that all three women feel that “the soul is not gendered,” so femininity must be put on, like a mask.

Femininity is enacted by Noh players, typically older men who impersonate beautiful young girls on stage. An awareness of the illusion, Vollmann explains, is part of the aesthetic value of Noh; beyond the borders of feminine costume and the complex code of the female mask, the elderly masculine throat and feet are always evident. Geishas and ordinary prostitutes perform femininity, at differing levels of elaboration, while ordinary women do the same to please their lovers and themselves. “When I was with my boyfriend,” says Vollmann’s Serbian interviewee, “I would feel very female. . . . It felt nice to be with him as a body.” Transvestites and transgendered women perform femininity through conscious and constantly challenging choice, while biological women have to perform it like it or not—and sometimes they don’t, as one of the most telling interview fragments reveals: “You constantly repair yourself, and you have no time to be in the moment. When you’re young you don’t understand what little power you have, which means that you don’t have it; and once you start getting older you spend your time worrying.”

There’s a reciprocity of illusion between the performer of the feminine and the audience. “What is a woman to me?” Vollmann asks himself, “the answer must be: A projection.” This idea functions very well encapsulated in the world of Noh: “Forgetting the impossibility it must lead to, I kiss the mask, whose loveliness distracts me from perceiving the essential bareness of the situation upon which my attachment has been projected.”

One of the ways in which Vollmann changed the game plan for American fiction was to rework the devices of self-referentiality and authorial intrusion which, in 1960s metafiction, were deployed as excessively self-conscious gimmicks. Where a sixties metafictionist would strut into the text for a star turn around his own cleverness, Vollmann flings himself into his own work like a human sacrifice. This tactic is startling in his early fiction, both in the historical novels where he defies logic by finding plausible ways to insinuate himself into scenes often hundreds of years in the past, and in works of more modern setting, like The Rainbow Stories, where Vollmann’s presence as a character in about half the narratives creates a fusion of fiction and post-New-Journalistic reportage. In several of his more recent works (like Poor People, and the gargantuan Imperial), fictional elements drop out completely. These books are near-pure documentary, with real anthropological and sociological weight, though Vollmann remains prominent in the foreground, reporting on his own reporting as he goes along.

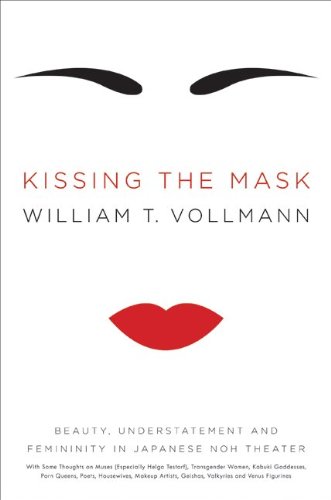

Vollmann has often illustrated his work with quick sketches like those nineteenth-century natural philosophers used to make, and more recently he has become a noteworthy photographer (the Imperial project, for example, has a separate volume of photos). Kissing the Mask is generously illustrated both with sketches (this time in a faintly Japanese style) and photos, of which the most memorable are the portraits of international beauties (labeled as such) that appear at the end of the volume. Vollmann has a gift for recognizing beauty where others would not (a lover with this capacity might be more successful than Casanova). About half the portraits meet conventional standards of attractiveness; the rest become beautiful because Vollmann finds them so.

There are also some peculiarly poignant images of the author made over into a woman by specialists in transgender cosmetology. The risks involved in this transformation may seem smaller than (say) driving over the mine fields of Bosnia, but Vollmann’s willingness to offer himself wholly and recklessly has always been touching, whether the danger is violent death or simply looking silly. Moreover, his apparent haplessness translates into true humility, a rare virtue well-understood by Japanese and one which probably helped him make his way behind the scenes of Noh.

Vollmann’s performance of femininity would probably not strike most people as beautiful. What these images and descriptions do suggest is that beauty itself (whatever that is) means less than the aspiration to it. “But who is this lady? Her eyes seem somehow a darker blue than mine. Is she fake? Her soft red-purple lips smile back at me. I toss my head and her hair changes to gold. . . . For an instant, and with joy, I believe in her, all the while experiencing aware, the knowledge that this impossibility cannot be sustained.”

Vollmann spends a good many pages on the life and work of Yukio Mishima, whose theatrical suicide has an affinity with some of Vollmann’s more extravagant gestures. However, Vollmann seems more or less immune to the vanity that drove so much of Mishima’s extra-literary behavior, and over the course of this book his own sensibility grows closer to “that master of aware,” Yasanuri Kawabata, on whom he comments more briefly. “It was such a beautiful voice,” Kawabata wrote, “that it struck one as sad,” and Vollmann comments on this “most characteristic sentence in his oeuvre,” that “the sadness, for him at least, comes from transience.” So too, perhaps, does the beauty.

“What is grace?” Vollmann begins to ask. The center of interest slips from beauty as concretized in the permanence of a carved Noh mask to the transient moment when beauty is performed: the fragile instant when the old man brings the young girl. Zeami has an image for it: “Piling up snow in a silver bowl.” Or in Vollmann’s Japanese-flavored words: “The silhouette of a carp slides by and vanishes behind or under the green-gold reflection of that pine tree. Just then the wind blows, and the reflection breaks up into myriad prismatic ovals of light green and white, pine needles duplicated, replicated, distorted . . . Grace is under the water, or reflected on the water. I can see it; why can’t I touch it?”

Though his style can be extremely subtle, understatement has not been one of Vollmann’s hallmarks. On the contrary, his exuberantly loquacious early works did a lot to explode the narrow world of 1980s minimalist fiction—somewhat in the manner of Samson in the temple. For him to react to his own sensibility in strictly understated Japanese terms may be a more radical transformation than his effort to turn himself into a woman.

“The greatest Noh narratives have to do with separation and desire;” and in this idea Vollmann finds his ground for personal engagement, when, toward the end of the book, he maps his own experience of lost love onto the aesthetic of Noh:

Once upon a time a certain woman loved me, and my faith in our mutual attachment resembled my belief in the immortality of that ecstatic moment when the actor in the Noh mask glides out of nothingness, moving more slowly than a geisha. . . . One morning she arose and went away. Once I comprehended that she was emancipating herself from me I entreated her to open her heart, but she had become enlightened, which must be why it is that my memory of her face has now become like my vision of the Noh actor’s mask turning slowly in the wind, shite of a ghost, lovely mask of a woman offering himself to be looked at.

The Zen Buddhist subtext of Noh insists on the folly of all attachments, but to understand that idea is not the same as to live it. Once Vollmann has lived it, through his own suffering of lost love, his abstract statement becomes more cutting. “No matter how attachment incarnates itself, says Noh, the finite will continue hatefully toward infinitude; the soul will be unable to die. Like erotic attachment, the love between parent and child must also be dissected by death or separation, and then what? Every human bond is a trap.”

It’s a grim conclusion for someone like Vollmann, whose affection for every imaginable form of human being is so powerful. Yet within the operating conditions of Noh (and Vollmann manages to pull artifacts as widely dispersed as Norse Sagas and Andrew Wyeth’s Helga portraits into the Noh context), it also seems inevitable. Such is the tragedy of love: So long as gender is performance, there is no way to reach through the shell and grasp the person or the soul of the other. “But this is not what I wish to believe,” Vollmann writes. “I want to kiss the mask, and when I put my lips against its wooden emptiness, I want to feel a woman’s tongue in my mouth.” What Noh tells him—beautifully, inexorably—is that no one can do that.

Madison Smartt Bell is a novelist and critic, whose 1995 book, All Souls’ Rising, was a finalist for the National Book Award. His latest novel is Devil’s Dream (Pantheon, 2009).