A COMEDY OF REMARRIAGE: THE PLOT SO FAR

The relationship between novels and movies is such a seemingly tired subject that one can be forgiven for yawning at its mention. This soporific quality derives in part from the many high school and college English courses that dutifully explore film adaptations of novels as a means of killing two birds with one stone and luring a visually besotted generation back to reading. Then there are the countless film-studies courses that approach it from their end. At professional conferences, armies of academics present papers singling out the filmic treatment of x or y novel. Usually, the comparison is made to the detriment of the movie, which is seen as crasser and cruder—recalling the New Yorker cartoon Alfred Hitchcock recounted to François Truffaut that showed two goats eating film cans, one remarking to the other, “Personally, I liked the book better.” Film is treated as the dumb blonde of media. Sometimes, however, the older medium, with its elitist pretensions, is viewed as corrupting the more innocent, populist folk art. Let us see whether we can bring some fresh air to this stale topic.

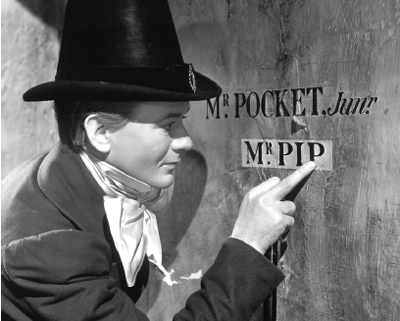

First, it may be necessary to question the received wisdom. One such premise is that it is easier to make a fine film out of a mediocre novel than out of a superior one, because the adapter will feel less reverent toward the source material. (In reality, a screenwriter who has had to adapt a weak novel can tell you that inheriting a lousy plot and thin characters does not make the job any easier.) A short list, barely scratching the surface, of beautiful films made from superior novels includes Mouchette (1967), Diary of a Country Priest (1951), The Leopard (1963), The Life of Oharu (1952), Pather Panchali (1955), Greed (1924), Day of Wrath (1943), Floating Clouds (1955), Little Women (1933, 1994), Wise Blood (1979), How Green Was My Valley (1941), Memories of Underdevelopment (1968), The Scarlet Letter (1927), Double Indemnity (1944), Nana (1926), The House of Mirth (1918, 2000), The Heiress (1949), Les Enfants terribles (1950), Mr. and Mrs. Bridge (1990), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Key (1958), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), Contempt (1963) . . . Even superlative novels that had seemed unfilmable, because of heft, canonical status, or interiority—I am thinking of Great Expectations, The Trial, Remembrance of Things Past,Wuthering Heights, War and Peace, Don Quixote, Madame Bovary—have yielded creditable versions, which at least partly succeed.

Another received truth is that the way to make a vivid adaptation is to cut loose from the novel as soon as possible. Some screenwriters boast that they read the novel once, then never go back to it, and there are directors (such as John Ford with The Grapes of Wrath [1940]) who say they never read the novel at all. There may be some egoprotecting here: Jean-Luc Godard was being a bit disingenuous in dismissing his source for Contempt, Alberto Moravia’s A Ghost at Noon, as a mediocre novel to read on a train, thereby downplaying the psychological dynamics he had borrowed from the author. But for every instance in which a rough, indifferent attitude (or the pretense of one) toward the source material resulted in a successful film, there are plenty of others in which the screenwriter and/or director took the original very seriously, such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos, who used the pages of Graciliano Ramos’s novel as the shooting script for his beautiful Barren Lives (1963).

(Quentin Tarantino, 1997)

READY FOR THEIR CLOSE-UPS: HYPERNATURALISTS

The most famous example of a filmmaker refusing to acknowledge any dividing line between novels and movies or to relinquish devotion to his source material is Erich von Stroheim. The tragedy of Greed—that his nine-and-ahalf- hour version of Frank Norris’s McTeague was whittled down by the studio to roughly two hours and its original negative destroyed—has become the central, cautionary myth regarding adaptations, like Icarus flying too near the sun or some medieval alchemist perishing in an attempt to convert lead into gold. But we could just as easily view Greed (even in its butchered form) as an exemplary model of adaptation. It is generally assumed that Stroheim went about trying to film the novel paragraph by paragraph—and indeed, there are many direct correspondences of that kind—but the truth is somewhat more complicated, as Jonathan Rosenbaum usefully notes in James Naremore’s collection Film Adaptation (2000): “In fact, Stroheim got so far inside the spirit and texture of the original that, like any good Method actor, he was able to generate his own material out of it: almost the first fifth of the published script of Greed, nearly sixty pages, describes incidents invented by Stroheim that occur prior to the action at the beginning of the novel.”

Anyone who has seen Greed—either in its 1924 studio release or in Rick Schmidlin’s fascinating 1999 four-hour restoration, which incorporates recently discovered production stills and dialogue cards—can attest to its thick texture of background objects, signs, faces, and clothing, all of which generate a poignantly convincing material atmosphere, brick by brick. Anyone who reads Norris’s novel will notice his similar fondness for amassing physical detail. Norris’s mentor in naturalist fiction was Émile Zola, who also loved to pile up the detail and to roam, like a tracking camera, over his chosen milieux. (See, for instance, the marvelous department-store descriptions in The Ladies’ Delight.) If Flaubert, as has frequently been observed, could be said to have anticipated crosscutting in the agricultural-fair sequence in Madame Bovary, Zola was even more important to the movies as avatar and inspiration. More than sixty adaptations of Zola novels have been made since 1902, when Ferdinand Zecca adapted L’Assommoir. But Zola’s usefulness to directors has been more than just as source. First, his descriptions convey the constant flow of life, such as has also been conveyed in documentaries and city symphonies from Lumière on, and which is the right and the privilege of the camera eye. Second, Zola’s penchant for deterministic fatalism channels that flow and gives it a narrative point. Jean Renoir, grand master of conveying a cinematic river of life that seems to spill out beyond the frame and lap around his fatalistic protagonists (Toni [1935], The Human Beast [1938]), acknowledged his debt to Zola not only by adapting several of his novels but by stating outright: “I believe that the so-called realist film is a child of the naturalist school.” And: “One usually takes Zola as a purely realist author . . . but what interests me in Zola is his poetry.”

This filmic discovery of the poetic resources in naturalistic realism, which derived from Zola, was so important to ’30s French auteurs such as Renoir, Marcel Carné, Julien Duvivier, Jacques Feyder, Pierre Chenal, and Jean Grémillon that their works were even grouped under the name poetic realism. Dudley Andrew, in his splendid study of this school, Mists of Regret: Culture and Sensibility in Classic French Film (1995), is quick to point out the debt that classic French cinema owes to novelists of the ’30s (think Simenon) when he speaks of “the evasive quality of ‘atmosphere’ that stands as an intermediate term between literature and cinema. Although atmosphere at one time may have belonged more properly to the poetic and the painterly arts rather than to the novel, which was considered the medium of social analysis and intrigue, in the 1930s atmosphere had descended like a cloud on the narrative arts of novel and film.”

AN EXPECTED TWIST: AVANT-GARDE STYLIZATION

The bane of many filmed novels is the episodic, that hurrying-along effort to cram in so many scenes from the book that high points get flattened and details blur. One strategy to circumvent that pitfall has been a highly stylized, austere, antinaturalistic approach. In Not Reconciled (1965), the first of many rigorous features by the duo Jean- Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Heinrich Böll’s Billiards at Half-Past Nine was used as the inspiration for a film about how a bourgeois German family copes with the period before, during, and after the Nazi regime. Rather than pack in as many sensational incidents as possible to capture a story spanning several decades, the filmmakers slow down their fifty-five minutes by patiently recapturing unhurried moments of being (such as a man smoking a cigarette on a stairwell or sitting down to his customary breakfast at a hotel), which achieves the Bazinian ideal of ontological reality. The result is a masterly contemplation of the way daily life goes on in the midst of historical upheaval. The Straub-Huillet team also adapted Kafka’s Amerika (as Class Relations [1984]) and Elio Vittorini’s Conversations in Sicily (as Sicily! [1999]) and made two features from Cesare Pavese’s Dialogues with Leucò (From the Clouds to the Resistance [1979] and These Encounters of Theirs [2006]), in both cases filming Pavese’s elaborate dialogues word for word.

Manoel de Oliveira, in Doomed Love (1979), filmed the famous nineteenth-century Portuguese novel of the same name by Camilo Castelo Branco, more or less in its entirety, by having a narrator speak voluminous voice-over texts when the actors are quiet. This method imposes an intentionally static rhythm, as the actors are obliged to stand around while the voice-over unfurls, though sometimes the camera goes its own way, tracking to a window, for example. The somber delivery of long, formal speeches by nonprofessional actors violates film adaptation’s received wisdom, which states that a novel’s dialogue must be recast and abbreviated so as to sound as natural as possible coming from the actors’ mouths. Yet somehow the results are mesmerizing. Oliveira explained that he found himself “making a film from a romantic work—but this work operates on two distinct levels. One is superficial, anecdotal, sentimental, and very explicit; the other is much more profound. I didn’t wish to remain with the first level. . . . Since I was adapting a work of literature to an audiovisual medium—a work of great beauty, moreover—I thought it would be legitimate to concentrate on the text, the words, and then let the images have a more serene form.” Oliveira subsequently refined his filmed-novel technique with Francisca (1981), based on Agustina Bessa-Luis’s novel, and Valley of Abraham (1993), loosely based on Madame Bovary. All of these experiments stubbornly resist that article of faith Avoid at all costs “the literary”; and in the process, they challenge that quasireligious dogma of film studies The visual must take precedence over the verbal.

SLOW DISSOLVE: THE STIGMA OF THE LITERARY

Being story-hungry, the cinema looked from its first, silent days to novels and plays for raw material. At the same time, defenders of this young, insecure medium were eager to assert that it had its own unique qualities, thereby putting forward a program of “pure cinema” and, in so doing, distancing it from the older media. The original sin, so to speak, was for film to ape the theater. Gilbert Seldes argued in 1929 that “not one single essential of the movies has ever been favorably affected by the stage; the stage has contributed nothing lasting to the movies; there isn’t a single item of cinema technique which requires the experience of the stage; and every good thing in the movies has been accomplished either in profound indifference to the stage, or against the experience of the stage.” The advent of talkies made the theatrical menace more palpable, by opening the floodgates to stage adaptations, and there were many highbrow writers on film, such as Rudolf Arnheim, who thought that sound spelled the death of cinema as an art form.

As it turns out, they were wrong. Talk, lots of talk, even combined with a theatrically inflected mise-enscène, led to many extraordinary movies, from Marcel Pagnol, Sasha Guitry, George Cukor, Jean Cocteau, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, and Orson Welles (who confessed he was always more interested in words than in images) down to Erich Rohmer, John Cassavetes, Woody Allen, and Alain Resnais, with his recent “film-theatre.” My point here is that a fear of language tainting the screen’s noble essence expanded from the theater as the principal villain to the literary per se, including novels, short stories, and a harderto- define gestalt. When James Agee, in praising Vittorio De Sica’s Neorealist Shoeshine (1946) to the skies, qualified his enthusiasm by saying, “Such feeling for form as there is, is more literary than cinematic,” it is not entirely clear to me what he meant by calling the director’s approach literary, but the tone of reproach is unmistakable.

Two forms of snobbery and prestige are involved here: the cinematic and the literary. Novels originally brought cultural cachet to movies. Classics and established novels of the day have always enjoyed the marketing advantage of being presold, familiar names, and the number of novels adapted for higher-budgeted, Oscar-friendly pictures (from Gone with the Wind [1939] to Memoirs of a Geisha [2005]) is much greater than for lower-budgeted ones. It was this built-in prestige attached to novels that raised the hackles of those Cahiers du cinéma critics in the ’50s, who would go on to constitute the New Wave. Truffaut’s attack on the French cinema’s “tradition of quality,” by which he meant lush, creamy films such as Christian- Jaque’s Charterhouse of Parma (1948) and Claude Autant- Lara’s The Red and the Black (1954), was also a veiled critique of the whole practice of drawing films from respected novels, which seemed insufficiently risky or personal. Of course, this hostility was suspended when, for instance, an auteur they admired, Robert Bresson, adapted Georges Bernanos. And Truffaut went on to reverse himself in his own directorial career by making many loving pictures drawn from novels, such as Jules and Jim (1962) and Two English Girls (1971). But some of the bad odor surrounding literary adaptations has remained. Even now, there are auteurs such as Otar Iosseliani who go on record that they will never engage in such a “stinking practice” as filming a novel: To be a true auteur, in their eyes, is to write and film an original screenplay.

In line with this antiliterary sentiment is a mistrust of two other devices frequently used in adaptations: voiceover and flashback. Screenwriting teachers tag these as forms of cheating and caving in to uncinematic practice. (This in spite of the many visually virtuosic films, from Citizen Kane [1941] to Goodfellas [1990] to Kill Bill [2003], that employ one or both techniques.) Sarah Kozloff, in her excellent book Invisible Storytellers (1988), analyzes the prejudice: “Obviously it is this emotional legacy of aversion to sound in general that provides the bedrock for all complaints against a particular use of the sound-track— voice-over narration. If one believes that all true film art lies in the images, then verbal narration is automatically illegitimate.” Kozloff also connects this aversion with another prejudice, this one derived from Henry James’s practice and so dear to writing workshops: Show, don’t tell. She writes: “Granted that voiceover narration adds a certain slant, or even definite bias, to a film—why is this bad?”

When an adaptation is criticized for being literary, it may also be a matter of sets, costumes, and overall smugness. In filmbuff circles, we learn to scoff at PBS’s Masterpiece Theatre and Merchant Ivory adaptations of classic novels as stuffy— meaning, visually uninventive. There is often something drearily mechanical about the way each scene from a Trollope or Brönte novel gets broken down into establishing shot, two-shot, and sneering or teary reaction shot, the adaption “genre” as coercive in its emotional signals as soap opera. On the other hand, Merchant Ivory made some subtle, astringent film adaptations, such as Mr. and Mrs. Bridge (1990) and A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries (1998), and British television rises above its own cozy-adaptation formula occasionally, as in Bleak House (1985) and Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky (2005).

It may seem like a jump to go from film to television, but these days so many projects start in one medium and end in the other that the distinction becomes almost academic. Generally, one looks to television more and more for the transposition of a novelistic mind-set to film or videotape. I realized this with a shock when, some years ago, I saw a miniseries, From Here to Eternity (1979), with Natalie Wood, that came much closer to the feeling of the James Jones novel, thanks to its relaxed unfolding over several nights, than had the overheated, Oscar-winning movie version directed by Fred Zinneman in 1953. Edgar Reitz’s remarkable 1984 Heimat series, made for German TV, has all the qualities of a great thousand-page novel, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s monumental Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980) is another model in this regard. For that matter, any television series with a developing story, be it The Sopranos or Gilmore Girls, allows more scope for the novelistically shaded, progress-and-regress evolution of its characters than a feature film, where the main character is expected to be “transformed” in one way only, usually positive. Television drama allows the writer to slip the noose of the three-act structure, and all the Robert McKee/Syd Field prescriptions for plot points, and to invite a more leisurely, discursive, novelistic sense of time.

Some filmmakers persistently exhibit a novelistic temperament. Luchino Visconti, after adapting Giovanni Verga, James M. Cain, Thomas Mann, and Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, had plans before he died to film Mann’s Buddenbrooks as well as Proust. Stanley Kubrick seemed always to require a novel to get his cinematic juices flowing. Not only did Mikio Naruse turn again and again to Fumiko Hayashi and Yasunari Kawabata for source material, but even his original screenplays continued to deemphasize the dramatic in favor of novelistic atmosphere and the patient accumulation of behavioral patterns. Of course, the influence flows the other way, too: Hardly a major novelist in the last hundred years has not been profoundly influenced by the movies.

(Fred Zinnemann, 1953)

THE PLOT THICKENS: INFIDELITIES

George Bluestone’s Novels into Film, which first appeared in 1957, is the ur-text of film-adaptation studies and the source of many of its received truths. Though dated (it is drawn from American movies between 1935 and 1950, when the Production Code still exerted a puritanical influence), it does raise key questions, and I have to admire the thoroughness with which Bluestone draws the parameters of a then-new field. He summarizes the difference between the production of novels and films as follows: “The reputable novel, generally speaking, has been supported by a small, literate audience, has been produced by an individual writer, and has remained relatively free of rigid censorship. The film, on the other hand, has been supported by a mass audience, produced co-operatively under industrial conditions, and restricted by a self-imposed Production Code.”

Bluestone’s method is to “assess the key additions, deletions, and alterations revealed in the film and center on certain significant implications which seemed to follow from the remnants of, and deviations from, the novel.” This plodding, backand- forth comparative approach has at least the merit of clarity, and it leads him to some conclusions that are still valid, up to a point: that movies privilege plot at the expense of character; that they play down anticlerical, sexually experimental, and politically activist elements to ensure the largest audience; and that they gravitate toward happy, triumphal, redemptive endings. Bluestone quotes a study showing that 40 percent of the film adaptations sampled were altered to give them a romantic, happy ending. I doubt the figure would be that high today, but studio executives remain in thrall to the falsely redemptive. Still, since Bluestone many film scholars have argued that a happy ending tacked on as the last minute of a feature does not negate all the feelings of anxiety and pessimism that preceded it. The happy ending is a convention that audiences know to take with a grain of salt.

Bluestone comes down hard on Vincente Minnelli’s Madame Bovary (1949) for its overly moralizing frame story of Flaubert’s trial. Today, our greater interest in auteurs might incline us to give more leeway to Minnelli (or Renoir, also lambasted for his Madame Bovary [1933]) and find intriguing a director’s separate treatment of the Flaubert novel. There are also dividends in the way of individual performances: Both Anna Karenina adaptations made with Greta Garbo, of 1927 and 1935, dropped the Kitty-Levin story, as Bluestone charges, but Garbo brings something new to our understanding of Tolstoy’s heroine, a weary, angelic forbearance, perhaps, just as Jennifer Jones’s ardent, dreamy, self-righteous Emma Bovary (the actress still dewy from her triumph in The Song of Bernadette [1943]) captures a piece of that moral sleepwalker’s ambiguous character in the Minnelli film. In short, it is possible for an adaptation to “betray” its source plot-wise and at the same time contain elements that augment our appreciation of the original.

Why even speak of betrayal when we can view these deviations as alternate paths that the novel might have taken, alternate lives it might have lived? The novelist pauses indecisively to consider whether to deal the heroine a happy or unhappy fate and chooses in the end a miserable one, but the alternative joyful, romantic one is like a shadow buried in the body of the text; the film adaptation helpfully uncovers it. The same holds for vulgarity. As a sometime novelist, I have often fantasized that one of my novels would be adapted to the screen and made much tawdrier, in ways that my refined good taste had regretfully prevented me from indulging.

We cannot avoid raising the whole issue of faithfulness when novels are made into films: Is it a foolish expectation or a valid one? Over twenty years ago, Dudley Andrew called for a moratorium on criticism that narrowly applies “the discourse of fidelity.” An entirely sensible position. And yet, after we have mouthed for the millionth time those platitudes about how each film needs to function as an autonomous artwork, about how fidelity to the spirit rather than to the letter is important, about the inevitability and even necessity of change from one medium to another, about the film adaptation being perforce no more than a digest appropriating some of the characters and plotlines for its own ends, might there still not be something unstoppably human in our hope that beloved novels be rendered faithfully on-screen, or at least not distorted beyond recognition? I am of two minds here.

On the one hand, I think it silly to regard the novel as a frail, endangered species that must be protected from the brutal movie producer’s hunting knife. I agree with André Bazin when he questions the sacrosanct, historically recent notion of “the untouchability of a work of art.” Every screenplay, after all, is an adaptation of something or other, a pastiche of experience and quotation. If a film delights audiences, maybe that should be the end of the matter. There are many stimulating movie adaptations that use novels merely as a point of departure, radically updating the plot, such as I Walked with a Zombie (1943; taken from Jane Eyre), Apocalypse Now (1979; from Heart of Darkness), Clueless (1995; from Emma), Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story (2005; from The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman), and Pola X (1999; from Pierre).

On the other hand, the problem of fidelity seems more acute when the film adaptation presents itself as faithfully following the book. In such cases, I admit, I am personally appalled by certain adaptations. What bothers me about the 1963 movie version of Tom Jones (one of my favorite novels) is not that Tony Richardson tried to find modern analogues for Fielding’s parodic humor but that his silent-comedy speed-up shtick is cheap and patronizing. Jane Campion’s The Portrait of a Lady (1996) drifts so far from the spirit of its model that I cannot help agreeing with Cynthia Ozick that it “perverts” James, even as I tell myself that it is perfectly valid for Campion, an auteur in her own right, to make the story more relevant by turning it into a Generation X erotic thriller. In sum, I do not think we can ever wholly discard concerns about fidelity, but we need a more sophisticated approach.

The recent collection of essays Film Adaptation attempts just that. The good part is that the various film scholars and critics are open and receptive to experimental, nonindustry product, and they challenge the old literary-cinematic dichotomy; the discouraging part is that they tend to do this by putting everything through the theoretical strainer of Barthes, Foucault, Derrida, Bakhtin, and Genette. Adaptation studies are freed from the onus of fidelity, only to be chained to the wagons of dialogism and intertextuality. Fassbinder is quoted as saying that his film adaptations constitute “an unequivocal and single-minded questioning of the piece of literature and its language.” In other words, a film adaptation should be the filmmaker’s critique of the novel. So we have evolved from the notion of the filmmaker as the barbarian at the gates of literature to that of the filmmaker as the postmodernist critic deconstructing it. I suppose it’s an improvement.

Film adaptations are like biographies, in that even if the writer starts out sympathetic toward the subject, a time may come when deference turns to hostility, by having to live in such close, subservient contact with another intelligence. Welles’s 1962 version of The Trial is both a superb spatial recasting of the novel and an insouciant repudiation of a kind of spiritual anguish with which the filmmaker seems to have been fundamentally at odds from the beginning.

The judgments we make of film adaptations must always be placed in historical context and in the light of changing fashions. Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, which seemed revolutionary when it appeared because of its sympathy for the common man, now looks rhetorically inflated, almost like a piece of socialist realism, with its camera shots tilting to the clouded sky. (Also, there are so many better Fords that we don’t need to protect this one.) Roger Vadim’s Dangerous Liaisons (1959), which transposed Laclos’s classic to contemporary France, seemed the height of raciness when it first appeared; now it is memorable mostly for its Thelonious Monk score. Greed and Doomed Love still have the freshness of their lunatic integrity. Recently, I saw The Painted Veil (2006), a movie directed by John Curran from a W. Somerset Maugham novel. It is a competent and affecting picture, with a terrific performance by Naomi Watts as the beautiful, shallow, adulterous wife of an idealistic doctor, who is transformed by her husband’s death. Many film critics tempered their praise by calling it “old-fashioned,” and indeed it is, not only because the adultery-in-the-colonial-tropics story and the theme of sacrifice seem fussy for today’s audiences but also because the craftsmanship of the adaptation is so unobtrusively intelligent. The Painted Veil is criticized as old-fashioned for making human sense of a now-dusty Maugham novel that was just the rage in the ’20s and ’30s.

A PROPOSAL: MOVIES CAN THINK

When someone like Bluestone states that “the cinema exhibits a stubborn antipathy to novels” (a claim I resist), I think that what lies at the bottom of this assertion is the idea that movies cannot think. “Or rather,” writes Bluestone, “the film, having only arrangements of space to work with, cannot render thought, for the moment thought is externalized it is no longer thought.” Leaving aside the exception of the essay film, which assuredly and overtly does think, I have to say that when I am in thrall to a sublime film masterpiece, such as Max Ophüls’s 1953 The Earrings of Madame de . . . or Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1952 Ugetsu (both, by the way, literary adaptations), I experience it as a continuous flow of consciousness—observant, melancholy, detached, worldly, commenting . . . in essence, thought. Perhaps I am being simpleminded here, and missing some subtle nuance. Bluestone argues that film “can show us characters thinking, feeling, and speaking, but it cannot show us their thoughts and feelings. A film is not thought; it is perceived.” His confident assurance that film “is incapable of depicting consciousness” is partly based on the idea that metaphors cannot be rendered on-screen, because the camera turns all phenomena into fact. I consider this an overly literalist understanding of the way metaphor operates. Similarly, I would take exception to the French aesthetician Etienne Souriau when he argues that films are incapable of inhabiting one character’s point of view, the way novels can, and that they therefore lack interiority. Film is capable of much more subjective interiority than these thinkers will allow. Even Siegfried Kracauer, who in Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (1960) peddles the old malarkey about language being the enemy of the cinematic, allows that “inwardness” is possible in films, concluding: “In general, the differences between the formal properties of film and novel are only differences in degrees.”

But Bluestone would have it that they are fundamentally at odds, impossible to cross-pollinate, like “apples and oranges.” He writes: “What is peculiarly filmic and what is peculiarly novelistic cannot be converted without destroying an integral part of each. That is why Proust and Joyce would seem as absurd on film as Chaplin would in print.” I don’t know about Joyce (although John Huston’s The Dead [1987] is a pretty good film) or Chaplin (who wrote a decent autobiography), but Proust has been well served in recent years. I am thinking of producer Paolo Branco’s commissioning of various auteurs to adapt different volumes of Proust, which led to Raoul Ruiz’s amazing Time Regained (1999) and Chantal Akerman’s superb The Captive (2000). What Ruiz does is take soundings of the Proust novel and reorganize them into a symphonic whole. He also boldly challenges the Bluestone assertion that “the novel has three tenses; the film has only one” by transporting a seated Marcel, as a spectator, into his own re-created memories. Proust mixes up past and present, dream self and real self, and this is what Ruiz does, too, with his thoughtful cross sections or samplings of Proust’s text.

I have been arguing that novels and films have more in common than is generally asserted. Perhaps they are like one of those screwball-comedy couples, analyzed in Stanley Cavell’s Pursuits of Happiness: The Hollywood Comedy of Remarriage (1981), who marry, divorce, and then, understanding that despite past infidelities they are better off together, submit to the comedy of remarriage. Kracauer’s maxim is suggestive: “Like film, the novel aspires to endlessness.” Once we understand that there is no limit to the intellectual or artistic complexity of which films are capable, we will be in a better position to appreciate the past and potential symbioses between the novel and the cinema.

Phillip Lopate edited the Library of America's anthology American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents Until Now (2006).