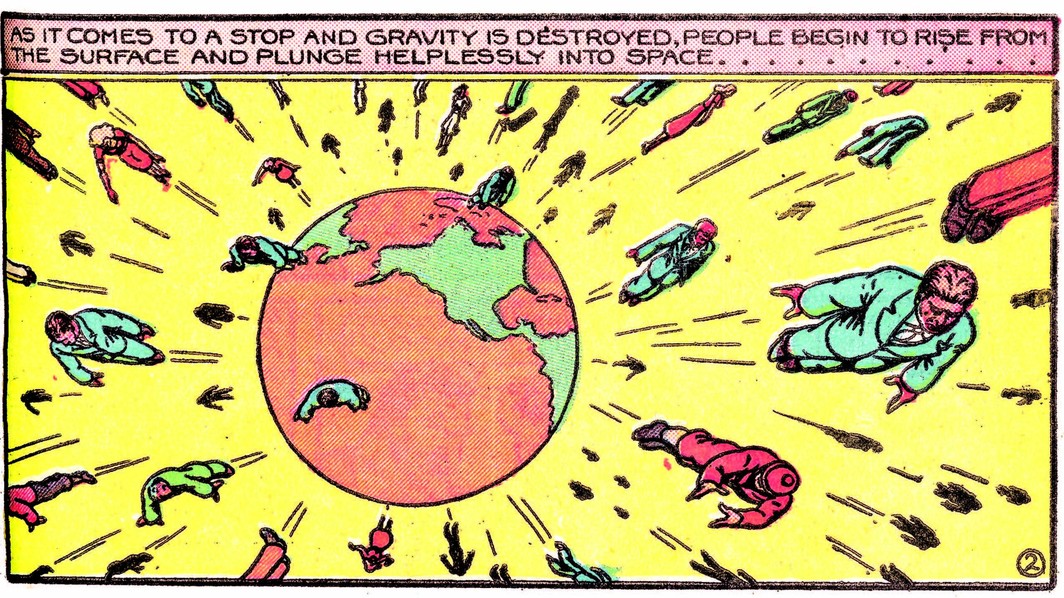

There is a man in a blue suit and a green and red skullcap piloting a red plane across a yellow sky. Crossing a lush jungle valley, he spots thousands of “gigantic royal panthers” and instantly declares: “I CAN USE THEM IN MY PLAN TO WRECK CIVILIZATION!” Though the colorful and crudely drawn adventure comics gathered in I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! read like the fevered imaginings of Henry Darger’s bully older brother, they are, in fact, the garish and terrifying work of Fletcher Hanks.

An obscure artist who briefly earned paychecks churning out pulps for titles like Fantastic Comics between 1939 and 1941, Hanks used a variety of pseudonyms to publish tales that starred Fantomah, “mystery woman of the jungle,” and Stardust, the “super wizard.” Little else is known about this nearly forgotten cartoonist, and he might well have been lost to the ages if not for the obsession of the comics artists and fans who have kept the memory of many such marginal figures alive (see Dan Nadel’s Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries, 1900–1969 for an excellent overview of this alternate lineage of American comics history, as well as a Hanks tale not in the present volume). Among them is cartoonist Paul Karasik. While associate editor of RAW in the early ’80s, Karasik was introduced to Hanks’s work, and it was instantly “jackhammered” into his brain. Over a period of years, he managed to track down the fifteen stories that make up this collection.

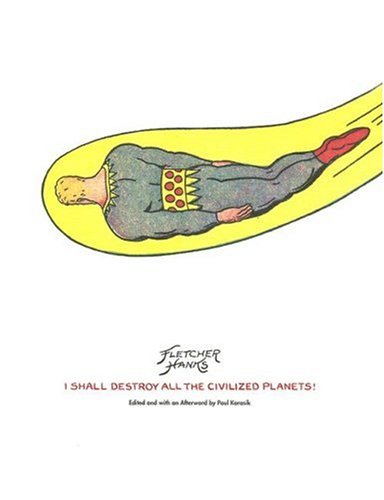

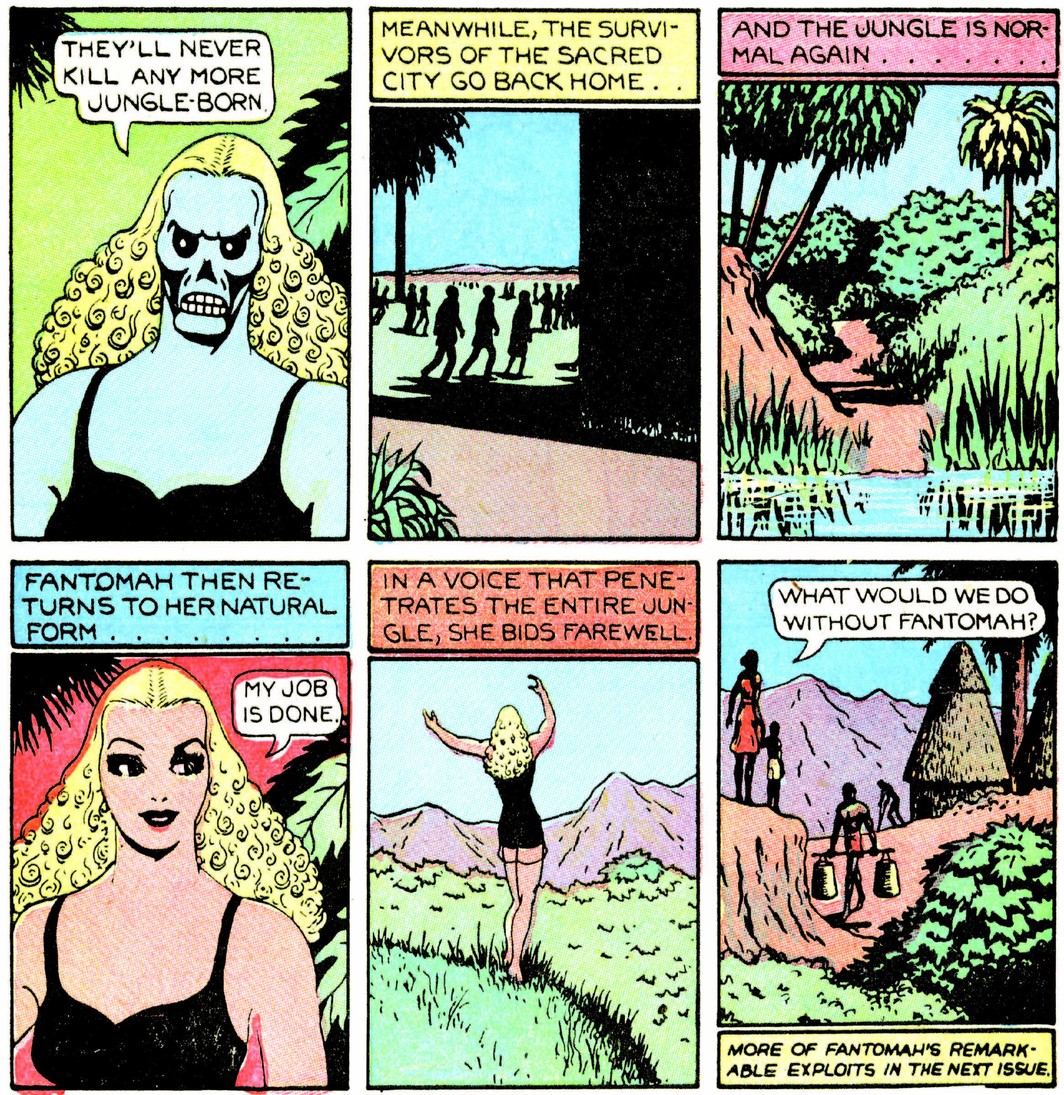

To open a Hanks comic is to be instantly thrown off balance. His drawing style is crude and distorted, an unrefined blend of the grotesquery and pulp surrealism of Basil Wolverton, Mad cover artist and creator of the Stardust-like sci-fi strip Spacehawk, and the blunt line and misshapen villains of Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy (not to mention Gould’s moralistic severity). Although Hanks’s ability to draw anatomy is feeble—his characters all seem to suffer from acromegaly— and his compositions are often unwieldy and random, he occasionally pulls off a stunning, beguiling image. When fighting evil, Fantomah, a kind of Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, with telepathic powers, transforms her petite, Tallulah Bankhead–like face into a menacing skull—still framed by lovely golden locks. Hanks makes idiosyncratic use of cartooning conventions like motion lines, star shapes, and various shimmering emanations and is particularly fond of groups of figures— gangsters, G-men, skeletons, gigantic royal panthers—floating limply in the air. These Rapture-like images are positively uncanny. His mostly flat primary and secondary hues, though typical of his era’s coloring, are intense and here beautifully reproduced, and the lettering is done in huge, bulky capitals that perfectly suit his ham-fisted narration and dialogue: “COME ON, YOU MUGS! GET READY! WE'RE GOING TO RELEASE OUR ANTI-SOLAR RAY!”; “SOMEBODY FROM ANOTHER PLANET IS USING A STRANGE AND POWERFUL RAY AGAINST VENUS!”

The template of a Hanks comic is boilerplate: Bad guys plan destruction, hero finds out and foils plot after some fisticuffs, hero punishes villains. However, an unusual number of the villains—whether gangsters, nihilist millionaires, or alien fiends—are not after money or power; instead, they want nothing less than the complete destruction of civilization (the book’s title aptly expresses the goal of these evildoers). Another common feature of the stories is the distillation of the typical superhero narrative. Half of an eightpage tale is given over to the meat of the story, in which the world—often New York City— is pummeled by bombs, tidal waves, and “flaming claws.” The hero is always wise to the plot on page 1 but somehow fails to save the day until page 4, and the villain is invariably defeated in just a few panels. The remaining four pages allow Stardust or Fantomah to unveil a surreal, brutal punishment: One villain is fed to a gold octopus after being flipped upside down along with his private island (it looks even weirder than it sounds); the blue-suited nihilist millionaire is turned into a caveman and left among the gigantic royal panthers he exploited; a group of gangsters is abandoned on a highgravity planet to stare helplessly immobile at piles of gold until darkness comes, “A BLACK NIGHT THAT WILL LAST FOR CENTURIES!” The understatement of the book is delivered by a jewel thief transformed into a hideous green lizardman, who sighs, "CRIME DOESN'T SEEM TO PAY!”

The cover of this handsome volume is clever and elegantly spare, though the endpapers suffer from Chip Kidd–itis (the blow up of Benday dots and newsprint texture is getting rather tired as a design element). The book consists almost solely of the stories, which generally alternate between Stardust’s and Fantomah’s (Big Red McLane and Buzz Crandall star in one story apiece), and this simplicity is refreshing in comparison with recent reprints that are overstuffed with essays, scrapbook photos, and examples of the artists’ “fine” art. The page numbers even mimic the stencil-like pagination of the source material. The book’s authenticity could have been heightened only by the use of newsprint or its archival facsimile. Those coarse, yellowing pages—never fully white even when hot off the press—are an essential component of old comics.

I Shall Destroy All the Civilized Planets! packs a final sucker punch in the form of an excellent afterword written as a comic by Karasik, who, in 1994, adapted Paul Auster’s City of Glass into a graphic novel with artist David Mazzucchelli (this essential work was reissued by Picador in 2004). Karasik’s style lies in stark contrast to that of Hanks. He draws in murky, sketched-out ink washes with scratchy panel borders as he relates his search for Hanks’s son, Fletcher Jr. The revelations the son shares about his father are devastating: Hanks, it turns out, was not a decorated air force pilot as Karasik had thought but rather a wife-beating drunk who abandoned his family in 1930 (stealing his ten-year-old son’s savings on the way out). He froze to death on a New York City park bench sometime in the ’70s. Karasik effectively incorporates images from Hanks’s work into his retelling of Fletcher Jr.’s tale, even inserting a panel that shows Stardust about to freeze a man alive (“IN YOUR FROZEN CONDITION–YOU'LL LIVE FOREVER TO THINK ABOUT YOUR CRIMES!”).

The cliché that the villains are the most interesting characters in stories does not apply here; in Hanks’s comics, they are generally as uninspired and indistinguishable as the heroes. Instead, both heroes and villains exist as a pretext for unleashing id-driven fury and destruction on the page. Stardust and Fantomah only deem it necessary to come to the rescue after allowing thousands of New Yorkers and “jungle-born” to perish, and when they do finally mete out justice, their vindictive and perverse punishments seem only to further the malicious glee that drives these fascinating, lurid, and creepy comics.

Matt Madden is the author of 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style (Chamberlain Bros., 2005).