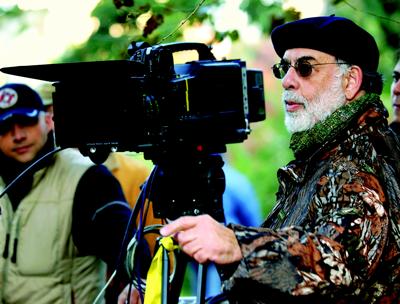

TRUE, FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA’S YOUTH WITHOUT YOUTH is the legendary director’s first film since an adaptation of John Grisham’s The Rainmaker in 1997, but one would have to reach back even further to find an appropriate comparison in his oeuvre. A remarkably challenging and absorbing film that Coppola paid for himself, Youth Without Youth is a return to the intensely personal work that characterized his early career. (Its portrait of technology and alienation echoes much of 1974’s The Conversation.) So it may come as a shock that Youth Without Youth is also a rather faithful adaptation of Romanian philosopher Mircea Eliade’s 1976 novella. In relating the story of Dominic Matei, an aging, depressed scholar who is struck by lightning one evening in 1938 and magically perfected into a perpetually youthful immortal able to absorb languages and knowledge at will, Eliade concocted a striking parable for the twentieth century’s dangerous love affair with technology. Coppola goes him one better, taking Eliade’s affecting portrait of progress versus passion and turning it into an epic about human consciousness, the duality of man, and the attempt to reconcile the affairs of the heart with those of the mind. The result is not only Coppola’s most personal film in decades but also one of his most complex and haunting.

BOOKFORUM: A lot of people were surprised when it was announced that you were filming a somewhat obscure Romanian novel. How did you decide to adapt Youth Without Youth?

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: Originally, for another project, I had been thinking about the twin challenge of cinematic language, which is the expression and manipulation of time while finding ways to try and tap into our unique human consciousness. It’s hard to explain it, but we all kind of know what it is: that little thing in your head that seems to be you, through which you see all your experience and feel your emotion. A lot of filmmakers in the past, even the great Sergei Eisenstein, had thought about the representation of human consciousness. He wrote about it in the second of his books [Film Form (1949)], I think. A friend of mine who was an Orientalist and a scholar pointed me to some quotes from Mircea Eliade, whom I didn’t know much about. I read some of these references, which ultimately led me to this novella. And it was a hell of a thing. It surprised me at every turn: Just when I’d think I got the story, it would turn a new page. It starts off with this lightning strike. And then he’s rejuvenated. And suddenly he’s talking to his double. And then the Nazis are after him. And he meets this woman who seems to be the reincarnated figure of an ancient Indian nun. I kept thinking, “What next?” I felt it could be made into a film that could be enjoyed on first viewing as a surprising story, but then you could see it again and find things to ruminate on more, about our perception of reality. Given my age and where I was at the time, I found myself with the opportunity to just go off and make it and not even tell anyone that I was making it.

BF: Watching the film, I sensed its style changing as it progressed.

FFC: I hope I followed in the author’s footsteps. I wanted to tell a story that just took lots of turns. Pretty much everything came from the novella itself or what I experienced reading it. And like a work of literature, I want the film to be able to work on these different levels. Plus, just the daily group process of making a film will surely change much of your plans about where you want to take something. On a film set, working together, you stimulate one another—I like to say collaboration is the sex of creativity. Just working with these other people that are exploring the same thing together with you, sparks fly, and different stylistic ideas come up.

BF: At the same time, there’s actually quite a lot of internal rumination in the novella. How did you go about making that cinematic?

FFC: The first step was that I was intrigued by these ruminations—I didn’t want to lose them. Eliade was a very bookish man who had devoted his life to learning. I hoped that following along in this, a little of that might rub off on me. But I had to bring the ideas forward so that it wasn’t just a guy talking about stuff. I had to find ways to make it available to the audience in an intriguing and original way.

BF: I noticed that the figure of Dominic Matei’s double was given more prevalence in the film.

FFC: Absolutely. The double was just that—an opportunity for me to externalize thoughts Dominic was having in his head. In the novella, the double basically appears in only one scene. I decided to keep him going longer, so I could use that device to express certain things. Also, I felt it gave the story a certain unity. If this is a Faust tale, then the double is Mephistopheles. So I seized upon him and kept finding other ways that I could keep him in the story. I did the same with the Nazi girl in Room 6. She was in only one scene early in the novella, but I kept her going—again for the purpose of having the means to externalize things that are, as you say, just internal ruminations.

BF: Did you read Eliade’s other work in preparing to make this film?

FFC: Well, they say that Eliade was a man who didn’t have a thought he didn’t publish [laughs]. So there’s a ton of work. I did read some of it. I can’t say all of it, ’cause I don’t think anybody could read all of it within a couple of years. But I read his stories, and I was struck by the similarity between him and Borges, who was a tremendous influence on him. They enjoyed these parable tales. That also comes from Sanskrit and Indian myth, which often takes the form of little parables that deal with the unreliability of time.

BF: Were there any parts of the story that stumped you—that you tried to incorporate into the film but couldn’t?

FFC: Well, for sure the section where Dominic goes to Dublin. I did shoot some of it. But a lot of people feel that section is more Eliade trying to get his arms around Finnegans Wake, and ultimately I wasn’t capable of pulling it in. I tried to. There are still parts of it in the film. I used sections of dialogue from it, such as the line that what we do with time expresses the supreme ambiguity of the human condition.

BF: Youth Without Youth also feels of a piece with much of your work, in that like so many of your films it tackles the tension between technology and progress on the one hand and the affairs of the heart on the other.

FFC: One of the beauties of being considered an artist is that you can do a film and then realize later that there’s a reason why you did it. And I’ve read enough to know that there are many authors who didn’t quite realize why they were drawn to certain works. I work hard, but I also work freely from my heart. So it’s only natural that prejudices or ideas or elements that are in me are going to come out. I leave it to others to connect the dots. But it’s true, I’ve always been fascinated by science and technology. I was a boy scientist as a child. I’ve always had a belief in technology and was good at it. I would build inventions when I was fourteen. That’s what attracted me to the cinema, in part, which is after all based on a machine.

Eliade was a man who had lived through World War I and World War II, and he was living in the cold war. A man who had lived through all that must have been sure that there was going to be a nuclear showdown. He talks about it in the story. He says there’s going to be a nuclear disaster around 2010. He goes on in a terrifying way to say that the few people left around will be affected by the electromagnetic pulse and will become superior persons. The double says that, and Dominic is outraged: “How can you say that? How can you be so cold as to say that?”

BF: It’s also very much a story of exile, very specific to Eliade’s own condition as a Romanian émigré. I was surprised and intrigued to see that this aspect of the story came through in the film very clearly.

FFC: Not to go into my own psychology too much, but I grew up in a family that moved every six months. I went to twenty-two schools before I got into college. I was always the lonely new kid. And that kind of impression when you’re really young you never can quite shake. Why did I make a movie like The Conversation, a film that features a lonely older guy who lives by himself and eavesdrops on people? There’s got to be some aspect of that in me. So I found myself very comfortable with the character of Dominic Matei, living alone on the run in different boarding houses, feeling like a kind of mutant. When people make personal films, all sorts of interesting connections will happen. It’s like an actor. An actor can’t do his work without using himself as an instrument. And a filmmaker who wants to be a personal filmmaker has to do the same thing.

BF: You’ve adapted a number of books over the years. Do you have a similar process for each work?

FFC: I like to fall in love with something about the project and then become immersed in it and swim around in it. One of the most wonderful things about being a filmmaker is doing the research. When I made The Godfather, I got a number of books to learn about the Five Families and how they came about and about the families before that. Knowledge is a string that keeps going back and back and back. For Youth Without Youth, aside from reading what I could from Eliade, I went to Bucharest and tried to learn the history of Romania. I read the entire history of the royal family and of the political movements that came out at the time of the Iron Guard—which was kind of an early form of fascism, only infused with religion as well. I’ve always felt that when you’re making a movie, you’re essentially asking a question. And when you’re done, the film you have is the answer.

BF: What is the question you’re asking in Youth Without Youth?

FFC: What is the nature of human consciousness? How did it come about? What I learned was that it was [our] extremely fascinating mental and emotional makeup colliding with language. I think that is the root of our consciousness.