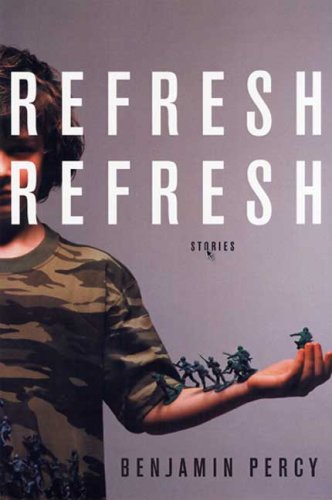

Death pervades the ten stories in Benjamin Percy’s second collection, Refresh, Refresh. These are gory, bloody, violent tales, yet they are narrated with such tenderness that they hang heavy with sadness. Percy sketches the lives of his protagonists, who live in Oregon’s rural high desert, in muted tones. Tumalo, Bend, La Pine, Redmond: The towns are as indistinguishable and unremarkable as their inhabitants—a melancholy region peopled with weary, mournful men who must cope with loss and loneliness.

The compelling title story, winner of the Plimpton and Pushcart prizes, is the acme of Percy’s style. Its tense, muscular account of two boys in a town emptied of its fathers, all marine reservists shipped off to Iraq, offers only the first of the book’s many renderings of quiet, painful desperation (as well as the first of many oblique yet disquieting references to the occupation). On leaving for war, the “Coors-drinking” men gave their families “the bravest, most hopeful smiles you can imagine, and vanished. Just like that.” As one of the boys hits “refresh, refresh” on his computer, hoping to receive an e-mail from his father, he realizes that these “disappeared” men “haunted us. . . . We began to look like them. Our fathers, who had been taken from us, were everywhere, at every turn, imprisoning us.” This voluminous emptiness saturates each of the stories. In “The Caves in Oregon,” the emotional void that develops between a husband and wife after she miscarries is embodied by the caverns that run beneath their house. Once, their exploration of the dark basalt chambers would produce in them “a happy sort of terror.” Now, “the longer they walk, the closer the walls seem to get, the narrower the passage.”

The hierarchy of the animal kingdom is everywhere at work, from nature shows on television, “where big animals tear apart little animals,” to the landscape’s brutal treatment of human intercessors. Percy’s addition in many stories of slow-boiling suspense can transform a tale of poignant suffering into one of shocking horror. “Meltdown” describes a man’s lonely travels within a radioactively contaminated Pacific Northwest. In a near-future dystopia less disturbing for its homicidal biker gangs than for its small groups of Hispanics who risk a slow, invisible death “because they feel they have nowhere else to go,” nature and civilization merge surreally: “Coyotes slink through the aisles of Safeway. Elk engage in rut-combat in Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square. . . . In the fields and in the streets are semis and tanks and planes, rust-cratered and woolly with grass.”

As a whole, however, the collection is uneven. The stories in its latter half meander, trailing off rather than closing satisfactorily. Percy occasionally reuses metaphors and clever turns of phrase in different stories. Likewise, though his characters are intentionally of a piece, their voices are unmodulated, and the language he employs in telling their stories is repetitive and, by book’s end, almost formulaic. Yet Percy’s storytelling can be brave and lean, and at his best he offers a bracing glimpse of unheroic men.