I honestly believe that 1/2 the people who

read about the Mitfords are motivated to do

so by a kind of fierce jealousy which drives

them where they do not want to go.

—Diana Mitford to Deborah Mitford,

May 13, 1985

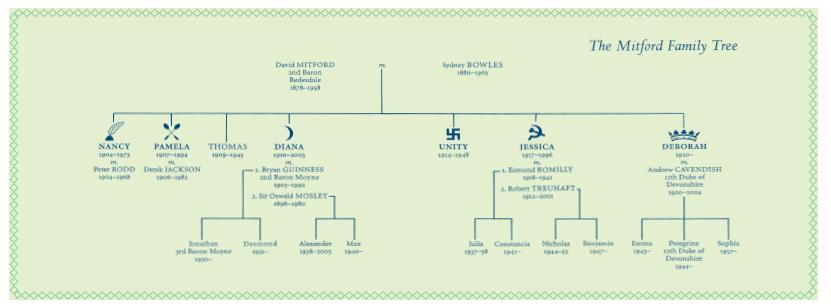

Several years ago, Charlotte Mosley found herself at lunch with her mother-in-law, Diana Mosley (née Mitford). Grumbling about the latest request by an outsider to illuminate yet another aspect of Mitford life, Diana looked at her youngest son, Max, and her daughter-in-law and said: “Why don’t one of you do something for a change?” Perhaps forgetting that Jonathan Guinness (Diana’s first son) had already published a family history (The House of Mitford) or that Diana and three of her sisters had each totaled a few thousand pages of autobiography (fiction and fact commingling uncomfortably in novels, volumes of letters, and memoirs), as well as the various biographies, family histories, and photo albums lining bookstore shelves across the globe, Mosley took up the challenge. She had known five of the six sisters (three very well) and had already published two volumes of Nancy’s letters and essays. The next step, naturally, was to sift through the twelve thousand surviving letters (over four million words) between the six sisters, not so much archived as stashed chaotically at the digs of the youngest, Deborah Cavendish, at Chatsworth.

As Mosley tells it, the whole endeavor lasted more than four years. “It took a year just to classify the letters. When I began, most of them were unsorted, still crammed into shoeboxes, stuffed into old brown envelopes or squashed into dusty plastic bags.” By the time she was done photocopying and filing the letters (some of which are ten to twelve pages long), they still took up twelve feet of bookshelf space. The volume, which weighs in at a manageable eight-hundred-plus pages and could easily supplement a healthy workout, comprises only 5 percent of their (often daily) correspondence. It begins with a letter from the second-oldest (and least writerly) Mitford, Pamela (age 18), to Diana (15) in the summer of 1925 and ends with a fax sent by Deborah to the dying Diana in Paris in late 2002.

Although the sisters wrote furiously and compulsively throughout their lives (Nancy and Jessica even from their deathbeds), they did not show the same concern for their letters’ preservation until later on. As a result, there are few surviving letters by Pamela to any of her sisters (none at all, in fact, to Unity), and while Jessica began making carbon copies of her correspondence in the 1950s (her archives are kept separate from her sisters’, at the University of Ohio), she destroyed all but one letter to Diana after a never-resolved break with her once-beloved sister over their extreme ideological differences. It was Nancy, the eldest and possibly most self-conscious, who implored Diana in 1963: “Throw nothing away. Handy tells me letters from Evelyn [Waugh] are worth £1 each now—from American universities—but a correspondance suivie of a whole family, so rare nowadays, would be gold for your heirs.” She unwittingly reinforced what Deborah had written a day earlier: “DON’T throw letters away, it’s madness!”

Until the next few volumes of correspondence are published, we cannot know exactly how Mosley edited the letters (many of which have been cut down to size, with nary a paragraph to spare), but she presents a multidimensional portrait of the sisters that approaches the truth about what made the Mitford girls the “Mitford Girls” in a way that none of the previously published tracts have managed. Her touch is light—she is not unduly enamored of the sisters or swept away by their deeply idiosyncratic styles—breaking down nearly eighty years of correspondence into nine distinct eras, allocating an appropriate number of pages to their cultural and historical contexts, providing comprehensive footnotes (often simply to distinguish Harold Acton from Harold McMillan), shifting her focus instead to the private circumstances of their lives together and separately. She illuminates personal details, cryptic references, inconsistencies, lies, and contradictions invisible to anyone but a family member, especially one who has spent the better part of the last three decades knee-deep in the Mitford archives.

The letters, candid and reflective––even those by Nancy, who never failed to milk a performance out of the most cursory note—allow the sisters to be defined within their own familial context, coming of age in the most turbulent half century in history, growing together, apart, and together again, surviving unusual amounts of trauma, their sharp eyes and tongues (Nancy quoting Voltaire: “To hold a pen is to be at war”) always trained on one another. After all, much of what the sisters developed into can be attributed to the fact that they were sisters. Constantly commiserating with, competing with, resenting, protecting, caring for, judging, and loving one another, they learned quickly that the savage world of their own making could be survived only with ample awareness, sharp humor, and an imperviousness to pain. Perhaps because of a totalitarian and unpredictably temperamental father, the girls learned to hero-worship men, which led to a great deal of misery for at least four sisters: Unity even died for one, planting a bullet in her brain on the day England declared war on Germany. Only Deborah, the youngest, who may or may not have had an affair with “The Loved One” (JFK) and developed, later in life, an unhealthy obsession with Elvis Presley (dead already), escaped any sort of upset.

The letters show beautifully how the girls bent and shaped the world to fit into their nursery microcosm, not the other way around. The sisters thus emerge out from underneath the People They Knew (Waugh, Churchill, Strachey, Betjeman, Kennedy; and yes, save Nancy, the whole lot met Hitler or knew him well) and Things They Did banners (attending Nuremberg rallies, White House inaugurations, coronations) to shine in all their odd, brutal, poignant, loving, fallible humanity, thereby explaining quite clearly how it was that the rest of the world could not help but fall under their spell.

Mosley—referred to in a footnote to one of Deborah’s letters to Nancy (1971) as a “brill person of about the year 2000 who will make a thrilling, silly book on the Last Correspondence Between People using Pen & Paper” and possibly reveling (like the reader!) in the sisters’ put-down of and disregard for Selina Hastings’s biography of Nancy—all but disappears into the background. But she walks a fine line as the relation of Diana, the most controversial sister of the bunch. Notorious for her extreme views and inability to come clean about her relationship with Hitler, her love for Nazism, and her unrepentant fascist tendencies, she has allowed history to paint her in broad, cartoonlike strokes and is the most in need of a postmortem makeover. Considered the Great Beauty of the family, she broke her marriage to the handsome, affable, and riche Bryan Guinness to marry and devote the rest of her life to Sir Oswald Mosley, the womanizing, shrill leader of the British Union of Fascists. They married secretly at Goebbels’s apartment in Munich in 1936, with Hitler in attendance. So devoted to him and fanatic about his cause was she that she was interned (at the request of Nancy, who described her as a danger to society) under Defense Regulation 18B for the duration of the war.

Although Deborah emerges as the central figure of the sorority, maintaining good relations with all her sisters, even Jessica, who purposefully estranged herself from the bunch, first by eloping with her cousin to Spain and then by moving to America, where she joined the Communist Party, Diana is the book’s revelation. We know how caustic, disloyal, and screamingly funny Nancy was, how domestic-pragmatic Pamela was, how sweet-but-doomed Unity was, how rebellious, incisive, and cheeky Jessica was, how self-deprecating, sensible, and good Deborah was, but Diana has been dwarfed by her friendship with the greatest villain history has ever known.

Whether Mosley’s intentions were to be revisionist with her mother-in-law’s reputation is unclear: What we find is that Diana is privately the most reflective sister of the six, with the largest intellect, the most voracious appetite for literature, and the most complicated inner life. Starting in the ’50s, she begins to assess her childhood, her choices, her feelings, and her mortality in a way her siblings wouldn’t dare. She is also the most forgiving of her sisters’ foibles and shortcomings and rarely undermines any of them. Her husband, Sir Oswald, is out of bounds, remaining firmly on his pedestal, and even though there are moments toward the end of her life when she considers her position, she does not change her mind.

Included (by no accident) is this letter from Diana to Nancy; Diana had just finished Chaim Weizmann’s Trial and Error: “I have read every word, it is engrossing and now I wish I were a Jew, well not now perhaps I should hate a settlement but it must have been wonderful to be Chaim.” In 1980, she writes: “It is much more painful to hate than to be hated.” And finally, in 1988, she writes: “I’ve been asked to be on telly for the Hitler centenary next year & refused. If I were an old spinster I would rush to voice my uniquely unpopular views but it’s not fair to my many descendants. Not that I would ever condone the crimes but I should have to describe the charm & the brilliant intelligence. So now nobody need worry.” Mosley attempts to explain Diana’s unrepentant attitude toward her youthful ideologies in terms of her husband: Had she fessed up to her mistakes, she might have had to include among them a large part of her life, having given over every minute of her existence after 1936 to indulging Sir Ogre (as Nancy fondly referred to him). Diana stuck to her guns, although we’ll never know whether she did so out of conviction or love.

Should the remaining 95 percent of the correspondence make its way out (in 5 percent increments, of course), some of the answers will surely be found. It is hard to imagine that the letters (and answers) won’t.

Jessica Joffe is a writer based in New York.