"O my God, I am heartily sorry for having offended Thee,” begins the Act of Contrition, a Catholic singsong lodged in the temporal lobe, the place where penitence gives way to sound and meter. Anyone raised on nursery rhymes or bedtime prayers knows the brain holds more tightly to cadence than to meaning. These rhythms of atonement are echoed in two studies of Hollywood censorship, both featuring another bit of Catholic verse, the pledge of the Legion of Decency. Drafted in 1934, the recitation that brought the film industry to its knees begins: “I condemn absolutely those debauching motion pictures which, with other degrading agencies, are corrupting public morals and promoting a sex mania in our land.”

Now, of course, the declaration is laughable in its Reefer Madness–like hysteria, and derision would become one of the cracks in the foundation of the industry’s self-censorship system, the Production Code Administration, overseen from 1934 to 1954 by Joseph I. Breen. But at the time, the avowal was serious. As William Bruce Johnson notes in Miracles and Sacrilege, “the response [to the pledge] was Capra-esque.” Somewhere between seven and eleven million people signed their names in response to the rising scandals in the tabloids (see Fatty Arbuckle’s notorious downfall) and the blatant sexuality on the screen (see Barbara Stanwyck in anything before ’34). The boycott yielded crippling losses for the struggling studios, which formed the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors Association (the precursor to today’s MPAA). The group, as transparent as OPEC or the Vatican, already feared government regulation as much as public rejection.

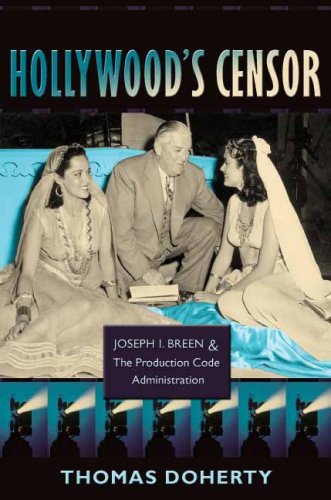

In Hollywood’s Censor, Thomas Doherty focuses on the Jesuit-educated PR flack who stepped into the breach between religion and film and managed a brilliant fusion, assuring church authorities he would rein in vice by policing all scripts and granting a Code seal to only the morally acceptable. The system in turn handily protected the studios’ monopoly on the exclusive production, distribution, and exhibition of their product.

Doherty details the shifts on Breen’s watch—Nick and Nora Charles trading in a king-size bed for twins—as well as the legendary battles, such as whether Clark Gable would be allowed to utter his famous line in Gone with the Wind. The author’s time spent combing through memorandums and correspondence is evident in the numerous glimpses he offers of the real man behind the curtain. There is Breen the unintentionally absurd: “We are concerned about the prominent use of the object known as the ‘G-String’ as the murder weapon”; Breen the peevish, sniping at Ernst Lubitsch: “If at any time you are a bit foggy as to what constitutes honor, purity, and goodness or where sophistication stops and sin starts, I’ll tell you”; and Breen the stricken, imploring Ingrid Bergman in 1949 not to leave her husband and child for Roberto Rossellini, a decision that “may well result in complete disaster to you personally.” His concern might seem poignant if he did not later oversee the PCA’s refusal to approve any Bergman-Rossellini collaborations, ensuring the actress’s exile from Hollywood.

More than a full portrait of the man, Hollywood’s Censor is a record of decision making, of rulings and reversals. Doherty’s penchant for punning on film titles doesn’t enchant so much as grate (“The Bells of St. Mary’s tolled a controversy”; “The path for The Bicycle Thief had been paved by Roberto Rossellini,” and later the film “skidded past two bright stop signs on the road to a Code Seal”). The author’s heh-heh-ing over the media circus surrounding The Outlaw and Jane Russell’s “matched pair” is especially cringe-worthy.

In the final chapter, Doherty considers Breen under the auteur theory, an intriguing argument, given that the man’s one-year foray into actual production as an executive at RKO was a total failure. Doherty’s premise, compelling as it is, might have propelled the book were it developed as a throughline instead of tacked on. Certainly, it raises interesting possibilities for an exploration of faith and film vis-à-vis André Bazin’s deeply held Catholicism and his belief that revelation is made possible by realism in film, especially in the work of the man who seduced Breen’s once-beloved Bergman.

Miracles and Sacrilege, too, is more history than film analysis. In his study, Johnson, an attorney, elucidates the forces—religion, commerce, and law—at play in censorship, building his narrative toward the landmark case of Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson (1952), in which the Supreme Court denied New York State the right to censor Rossellini’s The Miracle for “sacrilege,” thereby ruling film is protected under the First Amendment.

Johnson casts his net wide, drawing on the Ulysses obscenity trial, tracing the evolution of Italian and Irish versions of Catholicism, and citing Evelyn Waugh, Gilbert Seldes, and James T. Farrell, among others. Some of the jurisprudence can be slow going, but the steady supply of fact and anecdote is worth the occasional trudge. Johnson is particularly deft at explicating the 1915 case that decreed motion pictures were a business and not protected speech, a decision that would be undone in 1945 by an antitrust ruling that dismantled the studios’ vertical integration.

In The Miracle, a peasant woman (Anna Magnani) encounters a handsome stranger (Federico Fellini) on a hillside, takes him for Saint Joseph, drinks his wine, falls asleep, and wakes up alone. On discovering that she’s pregnant, she is filled with joy, believing she’s carrying Christ. But the villagers have nothing but scorn and ridicule for her news, and in the end they run the expectant mother out of town. It was a tale Rossellini knew well, and fortunately, he got to tell it.

Liz Brown’s writing has appeared in Design Observer, the Los Angeles Times Book Review, the New York Times Book Review, Newsday, and Time Out New York.