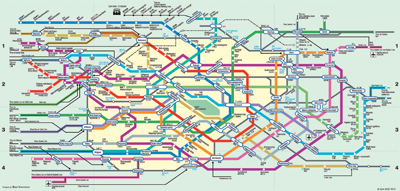

“Poor Charlie,” the Kingston Trio sang, “may ride forever ’neath the streets of Boston,” his trip on the MTA subway having gone awry because of a nickel increase. But fare change or no, navigating any big-city transit system is a task that would daunt even Theseus. The world’s largest—those in Paris, New York, London, Tokyo, Moscow, and Berlin—each boast hundreds of miles of track and at least several dozen stations. Routes snake through these cities, crisscrossing, connecting, and reconnecting; to get around, you need a plan. For casual collectors whose suitcase pockets bulge with maps from vacations past, this book presents a compendium global (over one hundred urban sites) yet compact. If you never get to Seoul, Recife, or Oslo, you’ll still know where to change trains for their airports. A selection of older maps for many burgs reveals not only system expansions over time but changes in cartographic design and conception. Since downtowns tend to be orbited by less dense locales, most maps share a basic visual grammar. Some can suggest the blocky grids of Mondrian; others, Brice Marden’s wiry detonations; and still others, as in the case of the Tokyo 2002 guide, combine both. Planners in most cities have chosen geometric clarity over geographic fidelity. During the ’70s, New York flirted with such a layout. Massimo Vignelli’s angular representation was loved by designers but disdained by straphangers. It was replaced in 1979 by a map that somewhat accurately renders the terrain aboveground. I carry it with me all the time, and although I’ve ridden its labyrinthine routes for thirty years, I can still get turned around, my ball of string rolling away, lost down some dark tunnel.