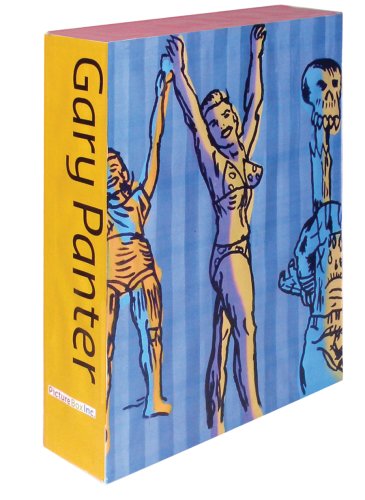

Gary Panter is a difficult artist to pin down. He’s a cartoonist, best known for his buzz-cut everyman, Jimbo. He performs light shows, makes puppets, constructs tiny cardboard architectural models, and writes and draws an animated Internet show. He’s done illustration work and album art. He’s even been a production designer, creating much of the surreal set for Pee-wee’s Playhouse (the job earned him three Emmy Awards), and an interior designer, for a children’s playroom in Philippe Starck’s Paramount Hotel in New York. But this two-volume monograph makes the case for his paintings.

Since his earliest comics work, Panter’s influences have included a full range of art-historical sources, popular imagery, punk, and psychedelia. Take, for instance, the climax of his 1988 book, Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise: As Panter’s punk-primitive hero attempts to disarm a nuclear bomb, each page that builds to the inevitable explosion, as well as those that describe its aftermath, features a different visual language. Cubism, Rayonism, Italian Futurism, Impressionism, and Surrealism filter through Panter’s ratty line and crude schematics. His paintings, as some seven hundred color plates attest, exhibit an astounding amplification of this idea: An array of images culled from cultural detritus (found packaging, comics, men’s adventure magazines, etc.) play atop grids and gradations of color, appear as misaligned superimpositions, perform incomprehensible narratives, and generally run amok. Panter has insisted that “a style should follow the idea, rather than the idea following the style; this visual roaming has characterized his entire career. His is a primal Pop, one that converts both high and low—Picasso and Kirby, Dante and Herriman, AbEx and advertisements—into a dense visual syntax, a hieroglyphics that both refines and explodes the image world in which we live.