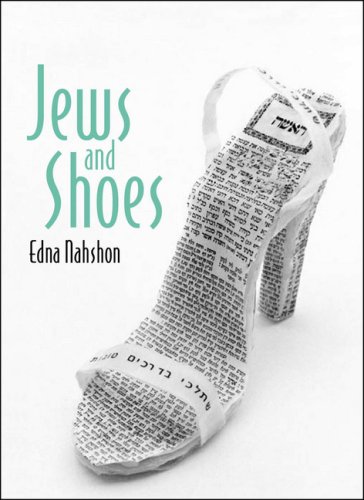

In days of yore, before the first JAP communed with a pair of Blahniks in the sanctum sanctorum of Bergdorf’s, Jews appreciated the metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties of footwear. In Jews and Shoes (Berg, $35), an odd collection of essays by Jewologists, folklorists, and an interdisciplinary mélange of cultural historians, editor Edna Nahshon cobbles together a surprisingly rich account of the Tribe’s journey via their footwear. Who knew?

The Jew-and-shoe story kicks off with Moses’s first divine order: “Draw not nigh hither; put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.” Ora Horn Prouser’s fascinating read of “The Biblical Shoe” sorts out this overdetermined gesture: Humility, lack of choice, unpreparedness, a covenantal legal relationship, and increased intimacy with God are all connoted by Moses’s unshoeing. Wandering and mobility are “so much a part of biblical thought,” she observes, that “shoes can symbolize . . . the protection and support necessary, provided by God during these times of travel.” (Fun fact: When Cecil B. DeMille commissioned twelve thousand pairs of sandals for The Ten Commandments, designer Salvatore Ferragamo, facing a dearth of information about the ancient gear, “ended up using some Victorian illustrations and his own imagination.”)

Not only do they make an outfit, shoes are vehicles of exile from divine presence. In “The Tombstone Shoe,” Rivka Parciack investigates the mysterious shoe-shaped grave markers that first appeared, like giant Frankenstein boots, in Jewish cemeteries in Ukraine in 1840, the year messianic cults expected the Jews to be redeemed and then march to Zion in their oxfords and pumps. As Madonna probably knows, shoes are big in Kabbalah: “The angels Sandal (Sandalfon) and Mattat (Matatron) are described as God’s footwear, for they function as separators and filters that mediate between the spiritual and material worlds. It is through these ‘shoes’ that the overwhelming intensity of divine power is reduced, preventing it from reaching revelation.” The foot, in turn, is likened to the divine presence (Shechinah) to be protected (by shoes) from the profane. The stone clodhoppers might be intended to guard vulnerable souls from demons cruising the graveyard. Retaining their shape whether feet are inside them or not, shoes are eerie metonyms for their human occupants. In Holocaust memorials, thousands of rotting shoes are poignant stand-ins for lost lives. A memorial in Hungary is a particularly haunting crime scene: A seemingly endless procession of bronzed boots and shoes lines a part of the Danube where the people who wore them were shot and drowned.

The myth of the Wandering Jew, dating back to the Middle Ages, is in fact a shoe story. A cobbler forced to roam the earth shoeless, the Wandering Jew embodies “unresolved Jew-ish existence” in the Diaspora. “When he was cursed, he lost his ability to work and live in society,” writes Shelly Zer-Zion in “The Wanderer’s Shoe.” Shoemaking became a metaphor for the Jew’s earthly existence. In a world “created by the process of exile,” shoes represent the chosen person’s physical groundedness or lack thereof: “The Wandering Jew, who exists in a twilight zone between the living and the dead, is a metaphor of the Jewish people, which is incorporeal, constantly on the edge of extinction . . . either swept into total assimilation and annihilation or driven back into their former wretched situation.” Oy.

Zionists like Theodor Herzl repurposed this undead anti-Semitic legend with a pro-Israel twist. They sought the right “metaphorical shoes . . . to march the Jewish people back into the history of living nations.” Advocating “muscle Jewry,” Zionist physician Max Nordau deemed sports clubs good for the Jews: “It was not the right shoes that would redeem the Wandering Jew but rather well-shaped and highly trained legs and feet.” In Palestine, young radical pioneers embraced the image of the hardy “New Jew,” the antithesis of the diasporic “Old Jew,” who was deemed a nebbish. The buff New Jews could defend themselves against foes and thrive on the land. These People of the Book sported Khugistic (biblical) sandals: “Footwear that symbolizes Israel’s secular identity should be given a name that connotes Judaism’s most sacred” reading material, writes Orna Ben-Meir in “The Israeli Shoe.” Schlepping by foot— literally “taking possession” of the land by walking through biblical scenery barefoot or in Khugistic sandals—was a Zionist rite of passage: “Rise up, walk through the length and the breadth of the land, for I will give it to you.”

Zionist sandals were an explicitly antibourgeois, unisex fashion statement: “As an intimate body covering and an article of locomotion [footwear] was a highly appropriate material symbol of nationality,” declares Ayala Raz in “The Equalizing Shoe.” Sandals were not only a “class badge but also a practical solution to genuine shortages encountered by the chalutzim (pioneers).” Shared shoes (often between five people!) “erase[d] personal singularity in favor of collective identity.” Asceticism was a status symbol—“Is there anything nobler than torn shoes on the feet of a leader? That is the ultimate symbol of the pioneer,” kvelled an early settler—yet the “socialist elite” kibbutzniks, who favored a “proletarian dress code,” coexisted with the secular Jews in Palestine who “did not renounce their petit bourgeois clothes.” Their occasional meet-ups produced a certain amount of sartorial weirdness. “Friday after work I had left for Tel Aviv,” reports Henya Pekelman in the 1920s. “I went to the ball . . . wearing a burlap dress that my mother had embroidered, and sandals without socks. . . . There were present twelve young men, all smartly dressed; and five young women clothed with silk dresses and red lipsticks. Everybody in the room stared at me in bewilderment.”

Shoemakers and shoemaking figure prominently in Yiddish proverbs. My favorite: “If you want to forget about all your troubles, put on a pair of tight shoes.” Associated with “lowly” things, the cobbler represented humility as well as world-weary wisdom—part nobody and bungler (“He’s a shoemaker, not a pianist”), part philosopher. The cobbler “studies the imprints of life on people’s shoes and repairs them as well,” writes Dorit Yerushalmi of Sammy Gronemann’s shoe-themed comedy King Solomon and Shalmai the Cobbler, a case of mistaken identity between a king and a cobbler. (Originally entitled The Wise Man and the Fool, it premiered in Tel Aviv in 1943 and was hailed as the first native Israeli musical.) The scrappy existence of cobblers embodied everything about the shtetl lifestyle that people wanted to flee. A step below tailors and innkeepers in public esteem, they nevertheless coined over six hundred Yiddish words related to shoemaking, rivaling the quantity of epithets for loser. In his vivid memoir, here titled “How to Make a Shoe,” Mayer Kirshenblatt, a former shoemaker’s apprentice, offers step-by-step instructions amid tsuris with leather thieves, a Jewish loan shark (“a butcher by profession”), and old-world squalor.

On a classier note, Pinkus’s Shoe Palace (1916) was the breakthrough hit for Ernst Lubitsch, whose early shtick later blossomed into “the Lubitsch touch,” the signifier of Hollywood sophistication. The son of a middle-class Berlin coat manufacturer began his career by caricaturing recent immigrants—the “ethnic” Ostjuden types—whom he passed on the way to school. (“Lubitsch’s wildly exaggerated body language seems to be the physical translation of a Yiddish idiom,” Jeanette Malkin notes in “The Cinematic Shoe.”) Now lost, his early films were deemed “the most anti-Semitic body of work ever to be produced, if . . . Ernst Lubitsch had not been Jewish himself!”

Pinkus’s Shoe Palace climaxes in a fabulous footwear fashion show (an early example of explicit product placement in film). Impish hustler Sally Pinkus (Lubitsch) is booted from his first crummy sales gig for refusing to wait on a man with holey socks. A natural at publicity (fibbing and flattery), he advertises his services by describing his own homely looks as “dazzling” and declares that “only first-class establishments will be considered; all other offers will be thrown into the trashcan.” He snags a celebrity client by vanity sizing her slippers, and she backs him in his own high-end Shoe Palace, where he triumphs as the suddenly suave impresario of a shoe spectacle: Sally “talks up each pair of shoes as the camera lingers on every heel and buttonhole of the buckled and laced and utterly urban fashions.” In the theater of twentieth-century retail, Lubitsch casts shoes as the star of the show and the vehicle for his Jew to schmooze his way to the top.

“Writing about sandals seemed like a marginal scholarly activity,” muses Ben-Meir, the Zionist fashion maven. “It is in the paradoxical nature of this type of dress that it is perceived as minimal and yet at the same time so symbolic and a significant clue to the Israeli psyche.” I, too, was amazed at how this “footnote” of a topic yielded so much as a survey of the Semites. Next up: Jews and Purses?

Rhonda Lieberman is a contributing editor of Artforum.