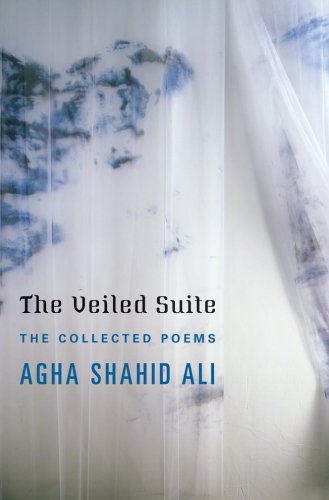

Arriving in the United States from India in 1975, Kashmiri author Agha Shahid Ali pursued both graduate degrees and his art. While quickly successful in the world of writing programs and academic presses, he explored in his poetry how readily expatriation could come to feel like exile. But as his collected poems, The Veiled Suite, make clear, he worked hard to find in such exile if not his true home, at least a safe house, as in book after book until his untimely death in 2001 he measured the distance between East and West.

Admittedly, this distance has been closing for a while. From the once-unimaginable East, twentieth-century poets such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Muhammad Iqbal worked to bring Urdu poetry into the modern era. This poetry was near and dear to Ali—his father recited it to him as a child. Early in his career, Ali translated Faiz (these poems are gathered in The Rebel’s Silhouette [1991]); in doing so, he tells us in his early poem “Homage to Faiz Ahmed Faiz,” “I touched my own exile.”

That collection is a necessary companion to this new volume. Through those translations, Ali first challenged the poetry of our moment, and they resonate profoundly with the personal and cultural devastations he documents in his own life. Some of the finest lines in The Veiled Suite can be read as a response to, for instance, these of Faiz’s:

There’s no sign of blood, not anywhere.

I’ve searched everywhere.

The executioner’s hands are clean, his nails

transparent.

The sleeves of each assassin are spotless.

No sign of blood: no trace of red,

not on the edge of the knife, none on the point

of the sword.

The ground is without stains, the ceiling white.

This forthright ethical cry to let the blood speak seems at first a world away from the grace, urbanity, and gentleness of Ali’s manner. But the power of his verse lies in the seemingly effortless way he challenges the reality of the seen—in his poems, what’s not there is more real than what is. Intended as a distraction from states of loss and deprivation, his wit is deployed with somber elegance in the early work, but increasingly so with what Yeats might have called a tragic gaiety. His elegy “In Search of Evanescence,” an early tour de force, is an extended balancing act, an exercise in making absence shimmer:

It was a year of brilliant water

in Pennsylvania that final summer

seven years ago, the sun’s quick reprints

in my attaché case: those students

of mist have drenched me with dew, I’m driving

away from that widow’s house, my eyes open

to a dream of drowning. But even

when I pass—in Ohio—the one exit

to Calcutta, I don’t know I’ve begun

mapping America, the city limits

of Evanescence now everywhere . . .

The magic word Evanescence, on loan from Emily Dickinson, blends grief and wonder and links distant lands as it bears emptiness upward. Ali went on to find such moments of transformation, even in the heart of historical upheaval, throughout The Country Without a Post Office (1997), where the motherland is itself dissolving, if far less gently than Ohio does. In this, the first of the two volumes that form the peak of his achievement, the poet envisions the devastation of his homeland, moving from the realm of the personal to an expansive poetry that maintains an integrity of feeling in the midst of political violence and tragedy. Kashmir is vividly evoked, all the more so for retaining an element of the fantastic. This is, as he tells us right up front, an imagined homeland, though one where

Kashmir is burning:

By that dazzling light

we see men removing statues from temples.

We beg them, “Who will protect us if you

leave?”

They don’t answer, they just disappear

on the road to the plains, clutching the gods.

In the second of these volumes, Rooms Are Never Finished (2001), the political calamity unites with the personal, unforgettably so in “Amherst to Kashmir.” This suite in memory of the poet’s mother is at once masterfully written, a psychologically acute anatomy of mourning, and a deeply informed cultural meditation. Picking up, once again, on Dickinson’s fascination with Oriental exotica (“If I could bribe them by a Rose / I’d bring them every flower that grows / From Amherst to Cashmere!”), Ali finds in her nineteenth-century whim the language for his twentieth-century grief, within which, as his poem proves, a charmed whisper can both console and devastate. The poet performs his own quiet holocaust, offering his mother’s body to the earth with an anguished sense of the fragility of pleasure. But the poem is a cultural inquiry as well as a personal lament. Ali threads the story of the martyrdom of the Shia hero Hussain throughout his elegy, keeping the history and hope of transcendental violence always before us, drawing strength from the strain of esoteric Islam that runs through his work:

So nothing then but

Karbala’s slaughter

through my mother’s eyes at the majlis,

mourning

Zainab in the Damascene court, for she must

stand before the Caliph alone, her eyes my

mother’s, my mother’s

hers across these centuries, each year black-

robed

in that 1992 Kashmir summer—

evening curfew minutes away: The sun died.

We had with Zainab’s

words returned home:

Hussain, I’m in exile from exile, lost from

city to city.

For all the grief and dislocation, in his later poems Ali found himself spiritually and poetically at one of the richest points of intersection in the Western literary tradition: where Europe and the kingdom(s) formerly known as Persia meet. His final book, Call Me Ishmael Tonight (2003), revitalizes the poetic form that links the two worlds. Akin to the sonnet, the ghazal has fascinated European poets since the time of Goethe. Developed in the early courts of Persian dynasties, it became a medium for both erotic reverie and metaphysical speculation. The ghazal married rhetorical sophistication—ornament, misdirection, and disguise—with poetic frenzy. A modern reader can find in its free-floating couplets a quintessence of recent theorizing about the sociopolitics of the sigh, about abjection, otherness, gender, performance, Orientalism, power dynamics, and identity. Long before Hegel, and with a great deal more eroticism, the poets of the Persian courts pursued the subtleties of the master-slave relationship. The form of the ghazal itself migrated, from Arabic to Persian, from Persia to points west, and from the Middle Ages to the present. Its lyricism lent itself readily to musical interpretation, and in the ’50s and ’60s, ghazal singing gained mass popularity throughout the Indian subcontient via radio broadcasts. Ali memorably invokes on more than one occasion Begum Akhtar, “the greatest ghazal singer of all time,” who died in 1974.

Ali no doubt felt entitled, by his Kashmiri roots, his own travels and travails, to claim it as his own. Perhaps the most daring and most charming of all this poet’s creations is the speaker of his last book. Typically, a ghazal concludes by announcing the pen name of its author. The pseudonym summons a spirit, not quite the poet, not quite not, who arises from the flow of words, a fierce, witty, strident, protective, generous sensibility, a Shahid who speaks to numerous friends by name, creating through words a community of the loved. (His final poem, which gives this collection its title, is an eerie and remarkable farewell. No mention of the cancer that would soon kill him, that would be tactless. But a mysterious figure arrives, as chilling as Shahid is consoling, for an encounter in which love and death are mercifully indistinct.)

The Veiled Suite amply testifies to the poet’s warmth, sensitivity, and delight in invention. But the imaginative strength of the poetry, it seems to me, emanates from a colder, more distant, more abstract analyst of fate, for whom cataclysm and isolation and cruel death are the hallmarks of modernity. And this side of himself demanded that the poet, ever studious, ever tradition-minded, search the past and the present, East and West, for ways to link distant realities, whether Kashmir to Amherst or one soul to the stars:

When through night’s veil they continue to

seep, stars

in infant galaxies begin to weep stars.

After the eclipse, there were no cheap stars

How can you be so cheap, stars?

How grateful I am you stay awake with me

till by dawn, like you, I’m ready to sleep,

stars!

If God sows sunset embers in you, Shahid,

all night, because of you, the world will reap

stars.

Joseph Donahue’s most recent books of poems are Incidental Eclipse (2003) and Terra Lucida (2009), both from Talisman House. He teaches at Duke University.