In October 1999, two titans of professional wrestling clashed in the ring—and all the announcer Jerry Lawler could do was laugh. “She’s got so many wrinkles, an accordion once fell in love with her face!” Lawler shouted, and again, when one of the combatants pummeled the other in the stomach, “She’ll never have babies again!” To be fair, the two contestants, World Wrestling Entertainment champion the Fabulous Moolah and her longtime friend Mae Young, were both in their seventies. And the comedy was as staged as the match. But the awkwardly anachronistic edge of the jokes—treating Moolah and Young like a pair of bawds in a Shakespeare play—was revealing about the way American culture responds to female wrestlers: We’re fascinated, but the whole idea makes us nervous, too.

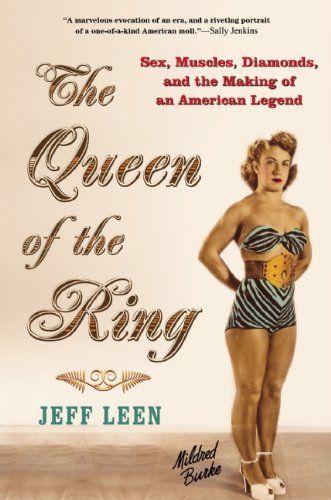

There are a lot of reasons for this, and Jeff Leen’s book The Queen of the Ring would have been much better if it had explored them with more curiosity. The Queen of the Ring is a biography of Mildred Burke, the first big name in women’s wrestling as well as the first woman to win genuine recognition (however grudging) from the wrestling establishment. Her story can’t fail to be enthralling, especially since she left behind the manuscript of a colorful and introspective memoir. But Leen keeps too much to the facts, leaving the psychological hollows that pock his narrative mostly unplumbed.

When teenage Burke went to her first wrestling match, in Kansas City in the 1930s, the game was in an early stage of its evolution, from slow-paced, muscle-bound “scientific wrestling” to the theatrical performances we know today. A. J. Liebling wrote that “conducted honestly, wrestling is the dullest of sports to watch”; a generation of showmen were just catching on to this truth and the commercial limitations it enforced. They introduced flamboyant new holds and falls and began to impose narratives on the bouts, casting certain wrestlers as “babyfaces” and others as “heels,” with in-ring behavior scripted accordingly. Wrestling impresarios also ginned up what were considered novelty gimmicks, like matches that included bears or women. And Burke dreamed of being one of those women.

She got her chance when she met Billy Wolfe, the main heel in her life. Wolfe was a mediocre wrestler looking for a break. He had already been sleeping with one female wrestler, but he liked Burke’s strength and speed in the ring. They went on the road as a carnival sideshow: Burke would wrestle any man who would take her on, and she always won, especially since some of the bouts were “worked,” or fake. The show moved to arena matches against men—opening for bouts between established male wrestlers—and finally to bouts with women, which gradually became a lucrative specialty. Throughout Wolfe and Burke’s joint career—they married in 1936, but the relationship was always purely business—he turned her and her opponents into characters with ongoing narratives that audiences could follow, and he hustled reporters mercilessly. For Burke and Wolfe, Leen writes, “newspaper attention was validation, the only means for them to claim legitimacy in a business they were creating out of whole cloth.”

As Wolfe catered to a growing stable of female wrestlers from the late ’30s through to the early ’50s, his PR challenge was to convince America that it was OK to watch women fight. Female wrestling was still banned in a number of states, including New York, New Jersey, and California, and religious conservatives often spoke out against it. So Wolfe had to create new personae for his wrestlers. On the one hand, he went to great lengths to prove that they were “all woman,” in the promotional idiom of the pastime. Out of the ring, Burke wore evening gowns, fur coats, and diamonds galore, once the money started coming in; she was always fully made-up, even while wrestling. “My resolve was to be a woman and a lady first, and a champion wrestler second,” Burke wrote in her memoirs. At the same time, Wolfe wanted people to come to his matches, so he played up how vicious women were, as if being all woman meant also being all bitch: “There’s no doubt that women’s wrestling is more brutal than men’s,” he said in a magazine interview. “The girls don’t stop to think or reason.”

This strange balancing act between dainty lady and hair-ripping, eyes-clawing harridan must have been difficult to sustain, and it’s instructive to see how differently Burke comes across in interviews with men, where she’s flippant and feisty, and those with women, where she tends to be more relaxed and natural. Many of the wrestlers in Wolfe’s employ had come from poor or difficult situations, and all were at risk for abuse, as aging lothario Wolfe abused and manipulated them, sleeping with a number of them, and playing his mistresses off one another. Whether you see Wolfe’s wrestlers as early feminist emblems or a sad bunch of circus performers following a maniac ringleader depends on your outlook. The truth is almost certainly somewhere in between, but Leen never works hard enough to discover it. Despite everything Burke went through in her life—the messy breakup of her marriage to Wolfe, the ensuing collapse of her reputation and career, her death in obscurity in 1989—Leen still views her as triumphant: “She ended as she had begun, with her unconquerable will.” Well, Burke eventually was conquered—as the sordid history of Wolfe’s management shows, she was fighting a fixed match against the world. Leen gives us the full chronology of her defeat but shies away from larger conclusions, and so The Queen of the Ring reads more like a fan’s scorecard than the rich cultural history it could easily have been.

Britt Peterson is deputy managing editor of Foreign Policy.