Technology can take unexpected turns on the path from an inventor’s lab to the shelves of Best Buy. During World War II, presidents Roosevelt and Truman used a cutting-edge voice scrambler called the vocoder, dubbed SIGSALY by the US Signal Corps, to communicate furtively with the Allies about details for such operations as the Normandy invasion and the Hiroshima bombing. Two decades later, as President Kennedy used an encryption device for back-channel communications during the Cuban Missile Crisis, vocal scrambling began its second life in music as singers started distorting their voices. In Hamilton, Ohio, soul-funk musician Roger Troutman fabricated his own distortion device from freezer parts, while futuristic electronic-funk group the Jonzun Crew warned their fans, enigmatically, about the video game Pac-Man.

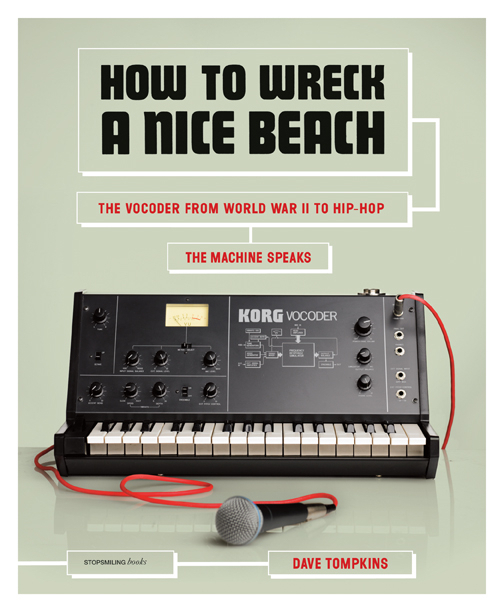

Detours such as these are brought to light by music journalist Dave Tompkins in his fascinating and entertaining debut, How to Wreck a Nice Beach. Ostensibly a history of the vocoder, the voice technology invented by Bell Labs researcher Homer Dudley in the late 1920s that evolved into SIGSALY, Tompkins’s narrative alternates between secret military transmissions and musicians exploring vocal distortion. The juxtaposition is meant to suggest what covert communications and intergalactic funk might have in common.

Dudley’s vocoder operated uniquely. It took an input (voice) and scrambled it in a predetermined manner; another, distant vocoder (like the one Churchill kept in the basement of a London department store) unscrambled that signal and rearranged it. It didn’t always work: The book’s title comes from a 1950s demonstration that mangled the phrase “how to recognize speech.”

The effect of the distortion sounds like somebody singing underwater with a mouth full of marshmallows, and by the 1970s the vocoder had a number of music-minded imitators. Peter Frampton and Troutman played the “talk box,” while Kraftwerk preferred a German-made Musicoder. Hip-hop producers learned about distorted vocals from acts like Troutman and the Jonzun Crew. In an interview with Tompkins, graffiti hip-hop artist Rammellzee calls the vocoder a “weapon”: It translates words into a language that, to him, only a few understand.

While Tompkins doesn’t linger on the parallels between his histories of military and hip-hop cryptography, the implication is ever present. He opens with a description of the SIGSALY setup, whose two turntables and a microphone resemble DJ gear. “Of the hip-hop civilians interviewed,” Tompkins writes, “none were aware of the vocoder’s service in any war, nor were they surprised by it.”

The choice not to elaborate may leave some readers in the dark. Hip-hop fans recognize the political currency in the art form’s history: It’s a music born of repurposed sounds, ideas, and technology. By failing to fold the vocoder into that culture, Tompkins’s comparisons between military intelligence and hip-hop remain a bit obscure.

His musical investigations aren’t all hip-hop focused, though—Neil Young and Herbie Hancock make appearances. Overall, the author favors personal anecdote (from both musicians and himself) about an experience with a song or album over exhaustive explanations of meaning. It’s a choice that, for the better, honors the vocoder with an air of mystery.