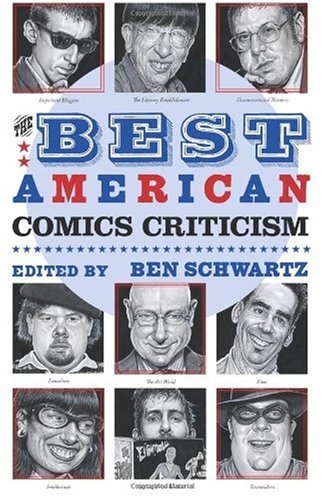

The road to respectability has been a long one for comic books; in fact, it’s felt like the home stretch for ages now. Despite all the progress, there’s been nothing like a canon of comics criticism. A few criteria for inclusion would then be expected from a book titled The Best American Comics Criticism, but editor Ben Schwartz tosses these aside (there’s an apology that “several of our authors are not American” because “not many Americans actually want the job,” but there’s no explanation for including court-case documents, Q&As, and comic-book excerpts under the banner of criticism). His own qualifier is “September 12th, 2000 . . . the day Pantheon released Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan and Daniel Clowes’ David Boring.” On that Tuesday morning, he writes in the introduction, “25 years of lit comics—from American Splendor and Love and Rockets—went mainstream ‘overnight,’ as well as the work of 1920s American lit comics pioneers Frank King and Harold Gray.” This book, he hopes, will “serve as a primer for this renaissance.”

Those are excellent books, and Jimmy Corrigan did make a splash with the world at large, but Schwartz’s invocations of events like the 1913 Armory Show are overbaked. What about pre-Y2K successes like Clowes’s Ghost World and Chester Brown’s I Never Liked You? Were Harvey Pekar’s Late Night appearances and the 1982 movie adaptation of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie not “mainstream”?

One comparison Schwartz reaches for is the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, for its mainstreaming of New Wave aesthetics. But the flashpoint of Bonnie and Clyde controversy—the stuffier critics saw only the lurid violence—was Pauline Kael’s dissentingly positive review for the New Yorker, which gave her a reputation for storming the gates of taste, forcing an embrace of lowbrow into a culture that had long resisted it. This seems anathema to BACC’s reverence for the label “lit comics” as opposed to (one supposes) “genre fiction.” The elitism goes beyond the subject matter: The years 2000–2008 also roughly coincide with the decline of print journalism and the rise of blogs. But only four of the thirty-seven pieces here were culled from the Web (one of those is a collection of Amazon Customer Reviews). In contrast, nine of the pieces are Comics Journal reprints, and—not counting the interviews—four are written by cartoonists who are discussed as subjects elsewhere in the volume, lending the proceedings a closed-circuit feel. And if this is indeed meant as a “primer” to the golden years so painstakingly defined, why then do nearly half the entries concern comics that first appeared more than forty years ago? An exaltation of Steve Ditko’s difficult and divisive Mr. A (1967–1978) follows a takedown of Ditko’s beloved work on Spider-Man (1962–1966), which has all the logic of presenting a celebration of Godard’s loathed Tout va bien (1972) alongside a dismissal of his adored Contempt (1963) as an introduction to the past decade’s cinema.

Much of the writing in BACC is, on its own terms, insightful and engaging. Among the standouts are Gerard Jones’s reportage on early science-fiction fandom, Howard Chaykin’s grumbling about Will Eisner, and Jeet Heer’s biography of Gasoline Alley’s Frank King. But the volume provides no context or guidance. “This curatorial ‘silence’ about the simplest issues relating to comics completely defeats the ostensible goal of building a discussion,” writes Dan Nadel, in a critique of the 2005 “Masters of American Comics” exhibit, and he could be talking about the book in which he now appears. “On what grounds are we meant to construct the dialogue?”