Jo Ann Beard is primarily known as a writer of that somewhat stigmatized genre, creative nonfiction. But what is creative nonfiction? How does it differ from the ineffably hipper "new journalism"? Same reliance on the stylistic techniques of fiction, but no facts, only memories and musings? Is "creative nonfiction" just the academy's mask for much-maligned memoir? For the fact is, those graduating from an MFA program like the University of Iowa's Nonfiction Writing Program, as Beard did in 1994, will likely need a day job. Beard, for one, became managing editor of the university's space-physics quarterly. She liked the comfort of it, and the flexible hours, and then on a day she left the office early, an unhinged Ph.D. student shot and killed the journal's editor—her close friend—as well as five others.

The essay Beard wrote in the wake of the tragedy, "The Fourth State of Matter," shows just what creative nonfiction can do. It makes a point of delineating first the quotidian bleakness of her recently separated life, and only then the shooting that bursts in on it. We meet her incontinent collie; then, obliquely, the future victims in her office building: "Space physicists, guys who spend days on end with their heads poked through the fabric of the sky, listening to the sounds of the universe, guys whose own lives are ticking like alarm clocks getting ready to go off, although none of us are aware of it yet." Visually acute, intensely personal, and all the more affecting for being emotionally muffled, the piece, which was published in the New Yorker in 1996, launched Beard's career. Her acclaimed and unclassifiable collection of personal essays, The Boys of My Youth, followed two years after.

Since then, she has published sparingly and with a proclivity for the spectacular accident or stark circumstance—subjects that naturally merit her style of unfolding single moments. Two of her most stunning essays came out in the past decade in the snappy literary journal Tin House—"Werner," about the eponymous protagonist's awesome escape from a 1991 New York tenement fire, and "Undertaker, Please Drive Slow," about Cheri Tremble, a patient of Dr. Kevorkian's. These essays agitate beneath their lean aestheticism, less "essay" than dramatic reenactment, effected detail by detail.

Creative nonfiction is a genre Beard interprets most creatively. So creatively, in fact, that when it came to the immersive imagining of Tremble's last moments during her physician-assisted suicide, the New Yorker was disinclined to run it. "You can't just make up stuff willy-nilly, refuse to call it fiction, and not run into some opposition," Beard admitted in an interview.

As a writer, the problem was this: If I called it fiction, pretended Cheri Tremble was a figment of my imagination, it wouldn't be interesting to readers, and if I treated it as journalism and wrote just facts, it might have been mildly interesting to readers but not at all interesting to me as the writer. So, since I'm the one doing the work, it's best if I do it my way, and let them take the highway.

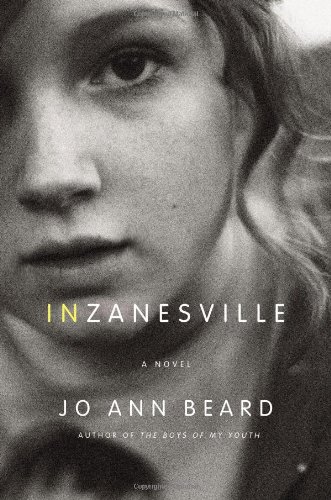

Given her elastic interpretation of nonfiction, it's surprising that Beard—for whom thirteen years have elapsed since The Boys of My Youth—would now write a novel. And all the more so because the nameless fourteen-year-old narrator of In Zanesville (titled after the Illinois township where the story is set) has a family almost identical to the one Beard describes in autobiographical essays like "The Family Hour": There's a trivializing older sister; an angelically agreeable younger brother; an aggrieved, chain-smoking mother; and a widely liked but sometimes disappearing and drunk father. The families, set a three-and-a-half-hour drive apart, are the same down to the dog and the parakeet. The main distinction is that Beard's fiction excludes some of the more distressing episodes from her memoir—the time, for instance, that her father crashed their new Impala into the viaduct and walked, blackout drunk, five miles home with four broken ribs and his teeth knocked "up into his head, behind his nose, perilously close to his brain."

That's because adolescence is trauma enough, one on which Beard hopes to fix our focus. Whereas Beard uses nonfiction to imagine how something so crazy could be real, fiction is a way for her to appreciate how something real could feel so crazy. And perhaps adolescence is even more intense in Zanesville, the "farm implement capital of the world," a town so insulated, it has largely evaded Google's roaming camera vans. The US Census from 1970, around when the novel is set, doesn't have population statistics for Zanesville, but in 2000 there were 399 living in the sort of archetypal American backyard that most American readers have never seen.

The Zanesville of the book is Insanesville only insofar as all outbreaks of insanity are part of the torpid routine of the town. The book opens, at its most sensational, inside the house of the six children whom the narrator and her best friend, Felicia, babysit all summer: "We can't believe the house is on fire," the narrator says. "It's so embarrassing first of all, and so dangerous second of all." Soot aside, the only damage is psychological: The narrator must watch her Harley-driving employer discipline the twelve-year-old boy who started the toilet-paper fire. Even before the father forces his son's arm into the stovetop flame, his wife has grabbed a beer to ice what will be the putrid-smelling burn. Yet the narrator never tells her own family—in part because embarrassment prevails, first of all. The narrator is perpetually self-conscious, and Beard's feat—showing the narrator avert her eyes from the scorching to the Wonder-bread wrapper melted into the side of the toaster—is to stylistically evoke how nervous attentiveness lengthens experience. Beard brings everything—from child abuse to a brush with a crush—to the same deliberate speed.

Teenage popularity, Beard reminds us, is about avoiding the mire of self-consciousness. At a slumber party to which the narrator and her best friend are surprisingly invited, a cheerleader can't unsnap her plaid bodysuit and so tries to pee around it. "I'm peed on!" she squeals and falls onto the carpet, where, churning her legs in the air, she cries for the most popular cheerleader to unsnap her. Literary fiction usually shies away from depicting the ridiculous extremes to which seemingly surly tweens will go to make each other laugh behind closed doors. Most authors writing about childhood, like Harper Lee and John Knowles, feel the need to pan for morsels of morality; Beard's strength is that she's content to administer childhood dramas in their natural doses.

With this tolerance for the uneventful, Beard captures the taffy stretch of time during youth and the endless waiting that is adolescence. To stay the boredom of detention, the friends cultivate crushes on the delinquents confined beside them. Eliciting a simple "Hi" from a crush is described as crossing a canyon, whereas the stagnation of a sick day is distilled down to "a sticky spoon and a glass of water with an expanded crumb floating in it." Beard's greatest achievement is that she shows girlhood as it actually is: grisly and trying; nerve-racking and often, when the narrator worries about her alcoholic father, ominous. Maturation, among other unpleasant things, reveals your parents for who they are—in this case, a man who starts dulling his senses with Drewry's at 10:00 AM and by dinner is angrily repeating, up to fifty-five times, "I'll say this about that." Unlike the tweens who inject their boredom with fluttering interest, the father flushes his away with the routine of repetition.

Even drastic events, like fires, are granted their slow and sometimes boring moments. Beard points out that there's a slippery slope between calm and crisis—no better than with the pregnant promise of quiet words like bloom and blossom, which suggest an imminent unwrapping. In her celebrated essay, just before Werner's building bursts into flames, for instance, Beard brews one of her most beautifully time-stopping sentences: "Deep inside the walls, three floors below Werner's apartment, a sprig of cloth-wrapped wire sizzled and then opened like a blossom." Choreographing the explosion to the muted unfolding of a flower has a stilling, refocusing effect.

It's this precise sensitivity that makes Beard a peer of "cosmic realist" writers like Annie Dillard and Marilynne Robinson. Rich but crisp lyricists, they hallow their subjects in the fleeting glow of perception. They emphasize the ephemeral for the permanent record. And there's no more natural guide for seeing afresh than Beard's narrator, with her wide eyes and bristling alertness. She registers an utterance as small as a suffix—an -er added to bloom, for instance—with radical sensitivity. "I hate the phrase late bloomers," the narrator says. "It sounds old fashioned and vaguely rank." Because what, exactly, could be late to bloom but body parts—blood and fat and coarse, wiry hair? A child's eyes can similarly electrify the landmark landscape of lockers: "Every once in a while you'll see a locker crammed so full that stray notepaper is coming out the air vents," Beard's narrator says. "There are one or two on each floor, and it's somehow disturbing, like seeing pubic hair poking out of a swimsuit." Anyone who was once young should recognize the shock of that gnarly shadow; it was, like the forbidden faculty lounge, something that you, as a kid, certainly weren't supposed to see.

These are the truths of junior high. And Beard's fidelity to the flexible language of childhood highlights them in the realest of her book's exchanges, such as this one between Flea and the narrator after a massive fight:

"You're something."

"Well, so are you."

"No, I'm not," she insists. "I'm being regular and you're being something."

In youth, simple words can be freighted, unbegrudgingly, with complex feelings. The meaning of something is absolutely clear, and perhaps because it's a word not distracted by intricate or alternative definitions, it allows Beard to capture childhood more accurately. But something, of course, can also stand for everything, and in that sense, fidelity to the language of a tween can be limiting. Particularly considering the liberties Beard takes with her creative nonfiction, fiction is, for her, a constraining force. Most of the twelve essays in The Boys of My Youth are written in the present tense: The narrator is an assertively naive but often uncannily clairvoyant child informed by having lived her own immediate future. But here Beard is pinned to the perspective of a fourteen-year-old. Walled off from the future, the narrator of her novel can only hope forward and reflect back.

What voice, however, achieves is a magically elastic effect on time. It shuttles you back to long-lost, endless afternoons. There are several ideas out there about why time moves faster as you age. Brain cells grow old and weary. Neural-conduction velocity slows, and one's internal measure of minutes stretches: While twenty-year-olds tend to estimate a minute at sixty seconds, give or take five, the average eighty-year-old will only call a minute after ninety seconds. Then there's the proportional explanation: When you're six, a year feels interminable because it's one-sixth of your entire life. But perhaps the most frustrating theory, because it seems so palpably within one's ability to control, is the notion that with age there are simply fewer novel experiences to dilate the days. The energy it takes to encode new encounters makes time feel full. It's by acting on this last idea, by attending to the oddity of the everyday, that Beard recaptures the magnitude—emotional and physical—of what can happen in a minute.

Francesca Mari has written for the New Republic and the New York Times Book Review.