As befits a well-practiced and much-lauded controversialist, Michel Houellebecq’s novel The Map and the Territory first incited a mini-hubbub over plagiarism upon its publication last year in France, then went on to win the Prix Goncourt. The lifted sections (as Houellebecq readily acknowledged) were from Wikipedia: long swaths of unremarkable factoids about things you’re probably not interested in reading about, like houseflies. If you find the whole pomo-pastiche thing a little tedious, there are other pleasures to be had, since a depressed, dyspeptic, and controversial writer named Michel Houellebecq gets gruesomely murdered in the second half of the book. The disquisition on houseflies comes into play because the body is in a state of advanced decomposition by the time it’s discovered. Extremely advanced.

What his killer does to the semifictionalized novelist, Houellebecq himself does here to the realist novel: namely, shred it to bits. As for the murder, I’m not giving anything away (besides, Roland Barthes gave it away first, in “The Death of the Author”): Plot is not exactly an imperative element in TMATT. Nor are characters—the protagonist, an artist named Jed Martin, is halfheartedly rendered at best. Genre is treated pretty haphazardly, too—following the murder, what had been a mild satire of the art world transforms itself into a somewhat enervated policier. (At least I think the art world’s being satirized, since Houellebecq puts quotation marks around phrases like “working breakfast” and mocks the prices of gallery art.) None of this matters because this is a Novel of Ideas, and, as the title indicates, the driving idea is the problem of representation itself. Assuming, as I think Houellebecq does, the exhaustion of the realist novel and the eclipse of the liberal humanist subject (whose creviced interiority literary realism was invented to excavate), how is social reality supposed to get depicted?

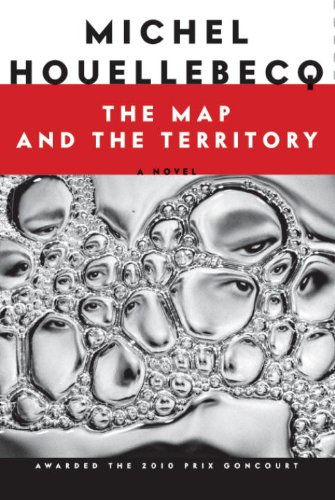

[[img]]

The phrase “the map is not the territory” gets thrown around in contexts where people are worried about other people’s tendency to confuse representation with what’s being represented. (It was first used by a Polish-American scientist and philosopher named Alfred Korzybski in 1931.) The classic literary elucidation is Borges’s one-paragraph short story “On Exactitude in Science,” which opens with a cautionary tale for overly conscientious chroniclers:

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the Entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.

In other words, the most scrupulous representation of reality—the one-to-one map—is also the most useless. So it’s clever of Houellebecq (too clever?) to invent a protagonist who achieves acclaim as a faux cartographer, reproducing Michelin maps as gallery art. Jed’s work catches on, in part, because it coincides with the French obsession with the terroir movement (the quixotic attempt to recapture a state of authenticity that never really existed), but mostly it catches on so that the novel can muse self-reflexively about the representation business: “Thus, Jed launched himself into an artistic career whose sole project was to give an objective description of the world—a goal whose illusory nature he rarely sensed.” As it happens, Jed’s own break with realism first becomes apparent in his portrait Michel Houellebecq, Writer—one of a series of paintings about contemporary occupations. Still, Jed “strives through various artifices to maintain the illusion of a plausible realistic background,” and he is not trying “to make a statement about realism in literature nor to bring Houellebecq closer to a formalist position that he had explicitly rejected.” If the phrase house of mirrors leaps to mind, that seems to be what Houellebecq (the real one) is going for.

In addition to the all the fun-house self-reflexivity, Houellebecq’s other strategy is to reproduce so much ostentatiously useless detail that the book itself threatens to become one of those unconscionable social maps Borges warned about. Along with the Wikipedia entries, we’re inundated with irrelevant statistics and factoids, technical specs for car engines and camera lenses, the business models of various companies, impromptu lectures on modern architecture, tourist data on Paris, and overlong stretches of other boring, irrelevant dreck, rendered in flat, robotic prose. It’s like an endless car trip with an autistic savant. Holding a mirror up to reality requires skill; holding up a vacuum cleaner requires only contempt for the reader.

All this would be enough to hurl the book against a wall if Houellebecq weren’t such a trenchant, sharp-tongued social commentator when he rouses himself to actually write. What saves the book is what an imperfect cartographer he is, filtering the lived experiences of global capitalism through his own numerous preoccupations and dreads; condensing vast human tableaux—the imagined communities of the new cosmopolitanism, for instance—into passing sardonic asides. On one of Jed’s girlfriends:

Olga was one of those endearing Russians who have learned in the course of their formative years to admire a certain image of France—gallantry, gastronomy, literature, and so on—and who are then regularly upset that the real country corresponds so badly to their expectations. It is often believed that the Russians made the great revolution to get rid of communism with the unique aim of consuming McDonald’s fare and films starring Tom Cruise; this is partly true, but a minority of them also had the desire to taste Pouilly-Fuissé or visit the Sainte-Chapelle.

Houellebecq’s France, simultaneously multicultural and homogenized, has become as crass and soulless as America, especially the art world. After Jed produces a series of paintings of business titans (Bill Gates and Steve Jobs Discussing the Future of Information Technology: The Conversation at Palo Alto) his prices climb through the roof, as despicable oligarchs vie to buy up their own portraits. Whichever direction Jed turns, somehow he keeps hitting pay dirt. When Jed’s gallerist says, “We’re at a point where success in market terms justifies and validates anything, replacing all the theories,” it perfectly captures the cultural moment, though I’d be hard put to tell you where Houellebecq stands on this, given the flatline affect of the book. Everything is equivalent, thus nothing matters.

Jed is deeply passive, a cold fish—he even espouses passivity as an artistic ideology. When he has thoughts, they take the form of chilly sociological observations: “Moreover, some human beings, during the most active period of their lives, tried to associate in microgroups called families, with the aim of reproducing the species; but these attempts, most often, came to a sudden end, for reasons linked to the ‘nature of the times.’” About Jed’s emotional remoteness, we’re told: “In terms of human beings he only knew his father, and still not very well. This could not encourage in him any great optimism about human relations.” But pretty much all the characters are spawned from this same shriveled gene pool: The policeman investigating Houellebecq’s murder had once been fascinated by human relations, which now arouse in him just “an obscure weariness.” A hostile old waitress, full of animosity toward everything, gets a brief walk-on solely for the purpose of twisting her mop in her bucket as if the world were “a dubious surface covered with various dirty stains.”

The general sourness takes a turn for the hilarious when Jed entreats the reclusive writer Michel Houellebecq to write a catalogue essay for an upcoming exhibit. A neurotic alcoholic, beset with a series of unpleasant physical ailments, the celebrated author is prone to scratching himself furiously until he bleeds: “I’ve got athlete’s foot, a bacterial infection, a generalized atopic eczema. I’m rotting on the spot and no one gives a damn.” He’s been shamefully abandoned by science, he complains; his life has become one long scratching session. Also, he smells—no great surprise since he lives in his own filth, spending most days in bed watching cartoons. He hasn’t lost all his principles, though, having recently given up the consumption of charcuterie out of respect for the intelligence of pigs. Unfortunately he soon relapses, and is found gorging himself on chorizo and pâté de campagne.

No one is better than the real Houellebecq, arch-cerebralist, on the general repulsion of human physicality. An annoying publicist has an “unexplored vagina”; also “her nose constantly dripped, and in her enormous handbag, which was more like a shopping bag, she carried about fifteen packs of disposable paper tissues—almost her entire daily consumption.” Of a chef Jed knows: “Anthony had put on a bit of weight since their last visit, as was no doubt inevitable; the secretion of testosterone diminishes with age, the level of fat increases; he was reaching the critical age.” When women are young, getting breast implants is a way of demonstrating their “erotic goodwill,” though “siliconed breasts are ridiculous when the woman’s face is atrociously wrinkled and the rest of her body degraded, flabby, and fat.”

In-your-face misogyny and misanthropy leavened with racial, ethnic, and religious slurs are what we’ve come to expect of Houellebecq: It’s his personal brand. But what of all the big ideas whizzing by—are these to be taken seriously? When Jed’s painting of Houellebecq is described as portraying pages of text “detached from any real referent,” it’s hard not to think that, after sending us on a bunch of philosophical wild-goose chases, the author is having a laugh on anyone old-fashioned enough to actually believe in “meaning.” Which leaves us with a collection of ideas that don’t really stick to anything, because the relation between ideas and consequences has been so offhandedly obliterated.

Textual playfulness “detached from any real referent” can be exhilarating. But what kept me reading is actually what’s least posthumanist and least postauthentic here, namely the traces of an authorial presence: Houellebecq’s scratchy, uncomfortable mind, his catalogue of hatreds and aversions, and the flurries of inventiveness and invective they inspire.

Laura Kipnis’s most recent book is How to Become a Scandal: Adventures in Bad Behavior (Metropolitan, 2010).