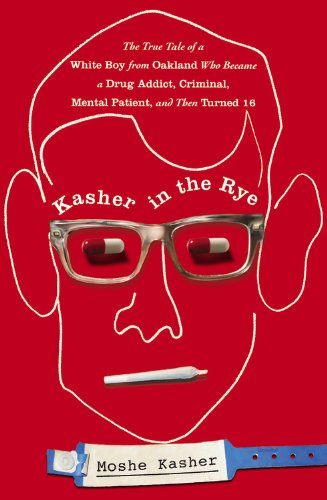

In Los Angeles comedian Moshe Kasher’s first book, the clever vitriol of the performer’s fast-paced stand-up routines meets the vulnerable sincerity of a man who “gave a fuck very much.” His biography, distilled in the book’s lengthy subtitle, The True Tale of a White Boy from Oakland Who Became a Drug Addict, Criminal, Mental Patient, and Then Turned 16, reads like a dayyenu refrain: Any one of these details “would have been enough” for readers to deem the writer’s adolescence both thorny and enthralling. And yet God granted more.

When it came to family life, Kasher was given quite a load to bear. In the early 1980s, his deaf mother (“a frantic, emotional waterfall of a woman”) kidnapped the infant Moshe and his older brother, David, relocating them from New York to the West Coast, out of their abusive father’s reach. Père Kasher, also deaf, subsequently remarried a hearing-impaired member of Brooklyn’s Satmar community, “the most bizarre” of all “Yiddish-speaking, society-rejecting, gown and fur hat–wearing Chassidic groups.” This became young Moshe’s abode away from crime-ridden northern Oakland, where his family survived on welfare and food stamps. Caught between various conflicting spheres—Jewish and secular; deaf and hearing; feeling alienated both at home and at school—Kasher, from an early age, developed a resounding insecurity, as well as a stellar sense of humor.

Kasher’s book catalogues the trials and traumas and of his pre- and pubescent years. Within the first section, called “Genesis” (like the Old Testament tome bequeathed to another notable Moshe), the comedian realizes that his big fat mouth can make him both stick out and fit in. “I figured out that the more I made people laugh, the less of a loser I would appear to be. I shucked and jived for my classmates, hoping like hell no one would figure out how scared I was.” He eventually ingratiates himself with a group of wayward boys in middle school, greatly relieved to finally feel accepted. “These were the first people in my life who weren’t asking me what was wrong with me. They didn’t give a fuck. There was something wrong with them, too. But more to the point, they got that the true problem was that there was something deeply wrong with everyone else.”

With his posse in tow, Kasher begins to dabble with drugs, finding in marijuana an incomparable reprieve from his pain: “The thick warm lava of euphoria fills in the crevices of your psyche, and you realize your soul was an electric blanket that hadn’t been plugged in until just then.” Much of part 2 of the book (titled “Fun!”) traces Kasher’s adventures with cannabis, psychedelics, and psychotropics. His initial enjoyment, however, quickly leads into “Fun with Problems,” and eventually “Just Problems,” a section chronicling his descent into severe addiction. After much denial, his dependence ultimately becomes indisputable. “The doomsday clock was ticking on my ability to defend how I was living.”

Kasher balances the heavier content of his memoir with playful turns of phrase and continuous, effortless jokes, infusing the prose with an essential dose of levity. His writing reveals a keen ear for rhythm, perhaps the result of a youth spent listening to hip-hop without parental restrictions. (“My brother . . . and I would blare X-rated rap albums with my mother in the room, unaware of a thing, often turning to us and exclaiming ‘I can feel the bass, I love it!’”) Whimsical rhymes, such as the writer’s names for variously splintered groups at school (“true-blue fuckups,” “square bears”), regularly punctuate the memoir, propelling it forward with metronomic cadence and lilt.

And so we proceed rapidly, bypassing years of therapy, institutionalization, and rehabilitation; wrong turns, rock bottoms, and subterranean-rock bottoms, finally bringing us to the moment when “the pain of existence transcends the fear of change.” In the fittingly titled last section, “Exodus,” Kasher describes getting clean, going to college, and repairing his familial relationships. Having soaked in the comedian’s words for the duration of the book, we come to accept his antagonistic bravado and his tender underbelly, a combination that renders his struggle both bearable and hysterical.