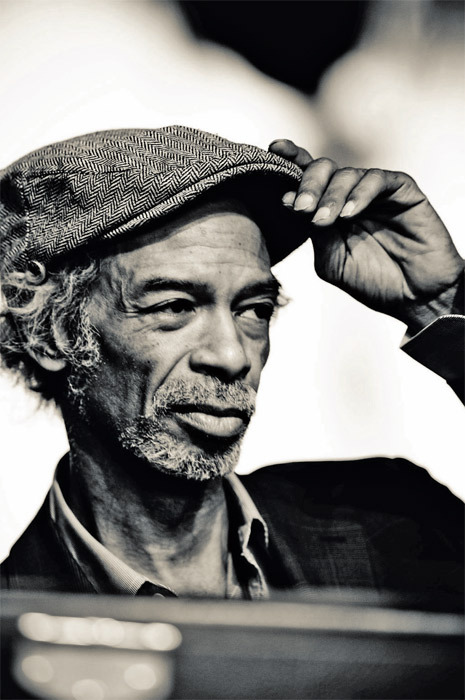

Years before he died last May at age 62, the legendary poet, novelist, and musician Gil Scott-Heron had been working on a memoir. Canongate Books, his publisher in Britain, announced plans to publish the book nearly a decade ago, and on the Canongate website there is a spectral recording from the early 1990s of Scott-Heron reading a chapter from an early draft of the manuscript. Now, the publication of The Last Holiday gives Heron the final word on an extraordinary life that has often been invoked as a prime example of artistic tragedy: a brilliant performer falling prey to drug addiction—the same scourge he depicted so memorably in songs such as “Home Is Where the Hatred Is” and “The Bottle.” After a prolific early career, Scott-Heron recorded only a handful of albums after 1982; by the ’90s, public laments over his “disappearance” became so common that Scott-Heron himself began to joke about it toward the end of his life. As he quipped to an audience at a concert in New York, “I read all of those reviews that said I disappeared. Wouldn’t that be great if I could add that to my act? Come up here and—poof!”

In many respects, the long-awaited appearance of The Last Holiday is just such a vanishing act. Scott-Heron devotes vivid stretches of the narrative to what he calls “disconnected pieces” from his childhood and college years, adds some passages spiked with sharp-tongued social commentary, and offers “scraps of yesterdays once tossed aside like gum wrappers.” But the book features surprisingly little about the artist’s life in the 1970s, when he was at the height of his artistic powers, publishing three books, releasing nearly a dozen albums, and performing around the world. And when it comes to music, Scott-Heron focuses primarily on Stevie Wonder’s four-month Hotter Than July tour, which featured him as the opening act. These concerts played an important role in Wonder’s campaign to make the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. a national holiday—an effort that bore fruit a few years later, in 1983. But Scott-Heron’s treatment of the tour as the pinnacle of his career is puzzling, and his explanation for lavishing such attention on Wonder’s push for MLK Day is anodyne at best: “We all need to see folks reach beyond what looks possible and make it happen. We need more examples of how to make it happen.”

The Wonder tour dominates the last third of the memoir in a way that only draws attention to all that the book leaves out. Scott-Heron almost completely ignores the last three decades of his life, and doesn’t discuss his personal struggles. The Last Holiday doesn’t mention that he was convicted twice on drug-related charges after 2001, spent much of the last decade in prison (for violating parole, among other things), and said in a 2008 interview that he was HIV positive.

Of course, some of the book’s unevenness can be attributed to the fact that the author died before it was finished: In a note included in the British edition (but inexplicably left out of the American version), publisher Jamie Byng writes that the book was constructed out of fragments: “The manuscript he left had been sent to me in a very piecemeal fashion over a number of years and written on various archaic typewriters and computers.” Nevertheless, the fragmentary state of the manuscript doesn’t explain the author’s silence on significant stretches of his life. When it comes to his problems, he only manages to write, with extreme understatement, “I have not been proud of everything that has happened or that I have done throughout my life.”

The Last Holiday does not deliver the voyeuristic pleasures of books like Keith Richards’s needle-littered tell-all, Life. At one level, it’s a relief that Scott-Heron refuses to wallow in the familiar pop-culture stereotype of the self-destructive black genius—foisted on musicians from Charlie Parker to Sly Stone. But there remains something undeniably tragic about the failure of Scott-Heron—who gave us some wrenchingly powerful depictions of the ravages of drug abuse in his songs—to confront his demons in this memoir.

The book also seems to promise a return to what Scott-Heron considered his first art form. When pressed, he called himself a “bluesologist” or, more humbly, “a piano player from Tennessee,” but he thought of himself first of all as a writer (even before his recording career was launched in earnest). Scott-Heron reached prominence as a literary prodigy, publishing two novels (The Vulture and The Nigger Factory) and a book of poems (Small Talk at 125th and Lenox) by 1972, the year he received an MFA from the Writing Center at Johns Hopkins (he was 23). Even after the success of his second album, Pieces of a Man, he “still wanted to be a novelist.” He was hired by Federal City College (now the University of the District of Columbia) in the English department, and he intended to stay there, until the momentum of his music career became inescapable. So one might say that with The Last Holiday, Scott-Heron comes full circle, back to the page.

But the memoir never achieves the formal economy or evocative force of Scott-Heron’s best song lyrics, which managed to be insouciant, vulnerable, and charismatic at the same time. In fact, he seems uneasy with any extended discussion of his musical career, particularly the great renown that he gained for the songs that most forcefully protested racist oppression—notably “Whitey on the Moon” and “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” Revealingly, he explains that from his childhood he “admired Langston Hughes, a man who set no limits on himself. And I didn’t want to get stuck doing one thing, either.” But this does not explain the key questions left hanging in the book: How did Scott-Heron think about the relation between literature and music? Why did some things work on the page, and others need to be sung?

The scattered passages about his music make it clear that Scott-Heron was never comfortable with his coronation as “the Godfather of Rap,” even if his spoken-word pieces became models for hip-hop. Public Enemy’s Chuck D said that Scott-Heron “set the stage for everyone else,” and rappers such as Mos Def, Common, and Kanye West either sampled his work or collaborated with him. But if the “Godfather” tag was meant as a tribute, Scott-Heron took it as an imposition. When asked in 2010 about his impact on hip-hop, he responded dryly, “I don’t know if I can take the blame for it.”

Scott-Heron also regarded the attention he won for more politically strident work as a de facto dismissal of the fuller range of his work—particularly his ballads and his searing tunes about heartbreak and hardship. When he was writing his 1974 hit “The Bottle,” a song with a groove as danceable as its lyrics are disturbing, Scott-Heron talked to a group of alcoholics outside a liquor store near his house in the suburbs of Washington, DC—“I found out,” he writes with characteristic gallows humor, “that none of them had hoped to become alcoholics when they grew up”—and he structured the verses of the song around stark encapsulations of their stories. Likewise, in “Pieces of a Man,” Scott-Heron powerfully distills a son’s understanding of his father’s shame at being laid off. Given his commitment to capturing such nuances of black life, Scott-Heron was irritated by being consistently pegged to a nationalist caricature.

So it’s not surprising that he has little to say in the book about his 1970 song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” although it is his most celebrated recording, and still a formidable parody of commercial culture (“The revolution will not go better with Coke / The revolution will not fight the germs that may cause bad breath”). “It was pretty obvious,” he writes of “The Bottle,” “that there was an entire Black experience and that it didn’t relate only to protest. We dealt with all the streets that went through the Black community, not all of those streets were protesting.”

Scott-Heron was a child of the civil rights era, and that may explain his impatience with the label “protest artist.” He was by no means politically quiescent (he integrated his junior high school in Tennessee, and led student demonstrations in college). But The Last Holiday makes it clear that for some African Americans of his generation, outrage at injustice also meant refusing to be reduced to outrage.

Indeed, Scott-Heron’s chapters on his formative life are some of the richest and most detailed sections of The Last Holiday. He was born in Chicago in April 1949 to a college-educated woman from Tennessee named Bobbie Scott and a Jamaican soccer player named Gil Heron. The couple separated the next year when Heron was offered a contract to play for Celtic, the Glasgow club that’s one of the best-loved franchises of European football. Nicknamed “The Black Arrow,” Heron père was a fascinating figure in his own right, one of the first black players to break into top-flight soccer in Europe. But he was never involved in his son’s life, and remains a peripheral figure in The Last Holiday. (Indeed, Scott-Heron says he was surprised when he performed in Scotland decades later and learned that his father had been a major public figure.)

In the wake of his parents’ separation, Scott-Heron was sent to live with his grandmother, Lily Scott, in Jackson, Tennessee. This was initially meant to be a temporary arrangement, but he wound up staying with her for more than ten years. She was an iron-willed, serious woman (“her sense of humor was a secret,” Scott-Heron said) who willed her way beyond some of the everyday injustices of segregation. When Scott-Heron was seven, his grandmother bought him his first piano, with the idea that he could learn to play hymns for her weekly sewing circle. She did not approve of the blues, but when he was alone in the house, Scott-Heron would tune the radio to WDIA in Memphis to listen to the music of John Lee Hooker, Rufus Thomas, and B. B. King.

When his grandmother died unexpectedly in November 1960, Scott-Heron’s life changed dramatically. He was reunited with his mother, who moved back to Jackson and took a job as a teacher. Bobbie Scott quickly became the most important presence in his life, and she is the most vibrant personality in The Last Holiday—an imposing woman who brooked no foolishness and supported her son’s ambitions as an artist.

They moved to New York City in the summer of 1962, settling first with relatives in the Bronx, and then in their own apartment in Chelsea. Scott-Heron showed some of his fiction and poetry to one of his high school English teachers, and she helped him gain a scholarship to her alma mater, the exclusive private school Fieldston in the Bronx. In an especially memorable chapter, Scott-Heron describes at length a ludicrous incident at Fieldston when he was nearly expelled for playing a piano without permission. But he has little to say in the book about his three years there, or about his life at home (even though he would go on to set his first novel, The Vulture, among a group of young black men in Chelsea).

In 1967 Scott-Heron chose to attend Lincoln University, he says, because so many well-known black men had gone there. Among its most distinguished alumni were Scott-Heron’s hero Langston Hughes, Cab Calloway, Kwame Nkrumah, and Thurgood Marshall. Torn between his studies and his fiction writing, Scott-Heron took a leave of absence to complete The Vulture, which was eventually published in 1970.

When Scott-Heron returned to school, he met Brian Jackson, a musically talented freshman with classical training. They formed a group called Black & Blues, which would become the basic nucleus of Scott-Heron’s band over the next decade. Scott-Heron briefly acknowledges in The Last Holiday that Jackson was “integral” to the band’s sound; he set Scott-Heron’s lyrics to music and played piano and flute. But he also vastly understates the importance of their relationship, which was one of the towering partnerships in American popular music, as prolific and telepathic as any lyricist-composer combination, from Rodgers and Hammerstein to Holland-Dozier-Holland.

Scott-Heron and Jackson recorded nine albums together, and on seven of them they share credit on the cover as coleaders. The men stopped working together in 1979 and apparently had a falling out. But there is no question that their collaboration should have been central to The Last Holiday, and it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that the book’s scant coverage of the 1970s could be rooted in Scott-Heron’s inability to affirm the full scale of Jackson’s influence on his life and career.

The many silences in The Last Holiday also call into question the moments that seem more confessional—as when Scott-Heron recalls his mother telling him he is selfish to the bone, or when he writes in the final pages that “love was not an active verb in my family or in my life,” and characterizes his emotional capacity as “stunted.” His protestations of inadequacy (“I am honestly not sure how capable I am of love. And I’m not sure why”) start to sound like rationalizations, and even the blunt cris de coeur in some of his song lyrics—for example, in the 1974 tune “Your Daddy Loves You,” dedicated to his daughter Gia—seem infinitely more eloquent than the clichéd self-deprecation that seeps into The Last Holiday. Scott-Heron writes that he loved his three children “as best I could. And if that was inevitably inadequate, I hope it was supplemented by their mothers, who were all better off without me.”

It may be naive to imagine that Gil Scott-Heron’s last words would be anything but unsatisfying and incomplete, a final evasion from beyond the grave. His outsize talent was destroyed by addiction—an extreme instance of a story that is all too familiar. The Last Holiday doesn’t even begin to come to terms with that truth, much less offer a confession or an alibi. It is something stranger: a compendium of attempts—sometimes riveting, sometimes hapless—by an artist to disappear while looking in the mirror.

Brent Hayes Edwards is a professor at Columbia University and the author of Epistrophies: Jazz and the Literary Imagination, forthcoming from Harvard University Press. He is currently working on a history of the loft jazz scene in downtown New York in the 1970s.