David Shields was a stutterer, an athlete, and he’s dying (we all are). Over the course of thirteen books he’s consistently and convincingly illustrated how those qualities make him the writer he is: concise, fearless, and urgent. More: Shields is a soulful writer, a skillful storyteller, and a man on the hunt for the Exquisite—something that can only be broadly described yet also includes deep nuances and exceptions. Shields is also, in a writerly sense, as brave as they come. He plunges, asserts, performs, stands off, and pushes forward. Art is categorical for David Shields: a “pathology lab, landfill, recycling station, death sentence, aborted suicide note, lunge at redemption”—where each category has mutable labels, and word choice means everything.

Shields’s brisk, hyperintellectual self-consciousness may actually represent some kind of perfect balance—a new poetics for our ADD, post-Great-American-Novel, homiletic, unprivate, reality-gobbling generation. His 2010 masterstroke, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, was a bundle of 618 aphorisms and unattributed quotations about the aesthetics of “reality.” Given the blizzard of dialectical responses that followed Reality Hunger’s publication, it’s clear that both the approach and the subject matter struck a nerve. In the manifesto Shields argues that fiction is dead—well, deadish. It’s not the genre that’s the problem but rather the slavishness of many of its practitioners. Much fiction (nonfiction, too) feebly pretends that life is made of order and structure, whereas reality is chaos. Art, according to Shields, can’t be resonant unless it embraces raw life.

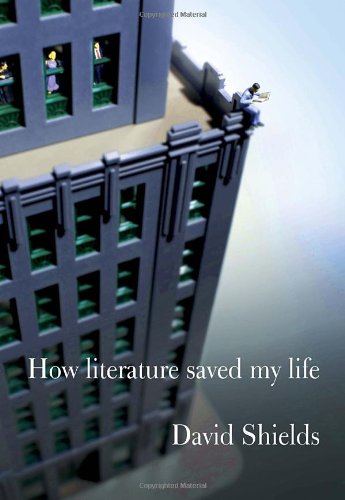

Mixing anecdotes, cultural analysis, and aphorisms, Shields writes with an urgent passion that makes books (sometimes dusty books) come alive. Demonstrating, even inciting, that passion is expressly what Shields is up to in his new book, How Literature Saved My Life: “I don’t want to read out of duty. There are hundreds of books in the history of the world that I love to death. I’m trying to stay awake and not bored and not rote. I’m trying to save my life.” How Literature Saved My Life is a kind of practicum to Reality Hunger: A Manifesto. Another way to say that would be: How Literature Saved My Life is a romance, the heart to the manifesto’s mind. It is the story of a man and his books.

Here, the collage mode extolled in the manifesto comes together with storytelling to demonstrate incidences of emotional resonance, where reality meets artifice. Shields’s own reality is a familiar blend of formative school experiences, the trauma of having parents, past loves, relevant physical conditions, the quotidian, and books. Mostly books. One section title is “Fifty-Five Works I Swear By” (Renata Adler, Proust, John Berryman, Borges, Cioran, Vivian Gornick, and more)—a gold mine of suggestions, but also a supreme intimacy: Here is my formation, children. You see, I, too, am built. Another trenchant chapter parses an Amy Hempel short story. Simultaneously, it’s about Hempel’s powerful story, her artistic skill, and David Shields. This is because, as Shields states in the title of his introduction, “all criticism is a form of autobiography.” The writing here almost always tries to establish how Shields and the books he loves overlap. Of Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station, he writes, “I’m obsessed with him as my doppelgänger of the next generation. My aesthetic spawn.”

Shields’s bibliography is made of examples (rather than prescriptions) of literature that “explores our shifting, unstable, multiform, evanescent experience in and of the world.” What works in art is massively subjective; his criticism is autobiography. “I like art with a visible string to the world,” he writes. In other words, the essayist has to be of this world and able to connect mind to heart, to use rhetoric to stir an emotional response:

According to Tolstoy, the purpose of art is to transfer feeling from one person’s heart to another person’s heart. In collage, it’s the transfer of consciousness, which strikes me as immeasurably more interesting and loneliness-assuaging. The collage-narrator, who has the audacity to stage his or her own psychic crisis as emblematic of a larger cultural crux and general human dilemma, is virtually by definition in some sort of emotional trouble. His or her voice tends, therefore, to be acid, cryptic, antic, hysterical (though hysteria usually ventriloquizing as monotone). I read to get beneath the monotone to the animating cataclysm.

Shields’s animating cataclysm is, I think, time. Time running out. The fact that, as my father would say, “each day brings me closer to my grave.” Or as Shields himself put it: The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead. Knowing this, he says in his new book, explains the melancholy “in the general populace.” Readers have no time for boring books, for books that didn’t have to be written, for books that don’t inspire empathy, or keep pace with a swiftly moving world. For a writer, critically, there is self-portrait, or rather proving that you’re not an alien, tweeting and isolated, through deep empty space. It’s the urgency of reaching out from the page, through the story, to glance against the real world and grab someone’s hand.

“I empathize with him completely,” he writes. “Wherever he goes, he’s walking across a graveyard. So are you. So am I.” “I couldn’t identify more closely with him if I crawled inside his skin.” “He somehow captured my ineffable lostness.” Shields has many different ways in How Literature Saved My Life of circling back around to the literary and emotional principle of empathy, or “transferring consciousness”: “We’re outside genre,” he writes, sounding for all the world like a literary theorist. “And we’re also outside certain expectations of what can be said, and in this special space—often, interestingly, filled with spaces—the author/narrator/speaker manages, in hundreds of brief paragraphs, to convey for me, indelibly, what it feels like for one human being to be alive, and by implication, all human beings.” Because knowing for sure, even for a moment, that you’re not alone in the universe might save a person’s life.

The way David Shields writes reads like an early Joan Didion—with tons more self-awareness and far less time (clocks move faster now than they did once; death comes fast). It’s elliptical and punchy and harvests the Self for subject matter. For the most part, writers who power forth with the courage of their convictions at their back don’t look over their shoulders. That kind of self-consciousness doesn’t often produce the kind of organic, fearless prose that Shields practices. Weirdly, his whole project is self-consciousness. (“The writer getting in the way of the story is the story, is the best story, is the only story.”) I would even go so far as to suggest that the revolutionary poetics Shields models is an aesthetic of self-consciousness—not effete or contrived, neither coy nor unemotional, not defensive, not weighed down with footnotes and peremptory explanations. Shields is muscular and self-conscious. He was an athlete and a stutterer.

There is a great deal of repurposed material here. A beautiful section about a mythological college romance is lifted whole from his early book Remote (1996). The spectacular piece about nighttime radio host Delilah is reworked from a New York Times article. I love the possibility (though I might be reading too much into how this collection was put together) that the same essay bears different meaning in this context, that it is in effect new again. Or maybe Shields wanted to make sure that we hadn’t missed it the first time around. The new and old, anecdotes and miniatures, all come together, just as a collage should. And because it’s a collage, one soon forgets the slightly less intriguing sections (I didn’t like reading the plot of The Taste of Others, a French movie I hate, but was happy to be reminded that Shields’s tastes are not infallible), or the ones already read, because something else interesting and mind- or heart-tweaking comes right after. (“The paragraph-by-paragraph sizzle is everything.”)

That forward movement replaces a suspense arc—which isn’t to say there’s no suspense here. This story is cumulative—not progressive, but a collage. There is no plot. There is linear (thematic) motion and a nonlinear mind. There is an abiding, utterly cerebral, question: Can literature save your life? It’s a giant, thrilling riddle. As for suspense—the fearsome persistence with which Shields pursues his answer builds the hope that in the last few hair-raising pages he might actually reveal how Literature did, one day not so long ago, yank him out of the path of a falling piano.

Minna Proctor is the editor of the Literary Review.