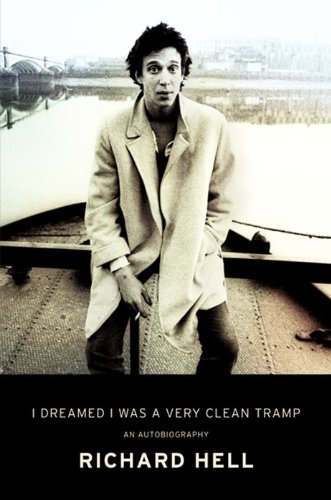

Speak, memory: “Nan’s pussy got damp but not soaking wet,” the musician Richard Hell recalls late in his new autobiography, I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp. “It was slick, like a squeaky rubber duck.” There are many shivery, illicit pleasures in this louche memoir of bygone bands and lost downtown haunts, including the author’s anatomically vivid, clinically surreal descriptions of past conquests. Hell writes of meeting—in a late-’60s poetry class taught by José Garcia Villa—a “sad, hysterical girl with red capillaries on her nose and cheekbones, and large breasts that looked like twin Eeyores.”

Think about that image for a second. Google “Eeyore” if you need to.

Anyway, he’s a breast man, Hell, that much is clear. Here’s him waxing ecstatic and resentful on a former rival, Patti Smith:

She was a natural-born sex waif and a pretty-assed comedian. She’d step out with her hand on her tight-cocked hip, all casual, if in-your-face, and jack out mind and body gush, giggling at herself like a five-year-old, under her deep-set eyes and her coal-black shag, begging to be fucked, skinny as a rod, massive tits deceptively draped in her threadbare overlarge Triumph motorcycles T-shirt, and then twirl away, denying you in favor of Anita Pallenberg.

The author kept journals in those years, back when a teenager named Richard Meyers left behind a rootless boyhood in Lexington, Kentucky, to come to New York City, intent on becoming what he became: a poet, an artist, a musician, a drug addict, a man who carried a dead turtle in a jar from one unfurnished apartment to the next. About the Neon Boys, the proto-punk band Hell formed in 1972 with his teenage buddy Tom Verlaine, Hell writes: “We wanted to be stark and hard and torn up, the way the world was.” Soon the Neon Boys would morph into Television, “a rolling, tumbling clatter of renegade scrap,” house band of a Bowery dive called CBGB.

So began a career that was more than the sum of its parts. Hell wasn’t much of a musician, and never really became one, though he’d go on, after falling out with Verlaine and leaving Television, to play in the Heartbreakers, with Johnny Thunders, and then to front his own band, the Voidoids. He was not a prolific songwriter, though what he did write tended to have an outsize impact—“Love Comes in Spurts” pulled off the nifty trick of being pop-punk before punk even really existed, while the perfectly nihilistic “Blank Generation” pretty much invented the Sex Pistols, the Ramones, and all that came after them.

Instead, as his memoir makes clear, Hell was a virtuoso of taste, a critic with a sensibility so fine and unconventional it bordered on its own form of art. In Tramp, he digresses at illuminating length on the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the poetry of Dylan Thomas. The demimonde of downtown New York in the ’70s is a familiar, even exhausted, subject—everyone alive and below Fourteenth Street in those years has their own portentous Allen Ginsberg encounter to relate. But only Hell, propositioned by the older poet one day while working a construction crew, would be reminded of “Walt Whitman admiring the sweat-sheened torsos of laborers.” And only Hell would turn Ginsberg down, not because he wasn’t gay—though he wasn’t—but because he didn’t think much of Ginsberg’s poetry.

“Half the beauty of rock and roll,” Hell writes, “is that ‘anyone can do it’ in the sense that it’s not about being a virtuoso but about just being plugged in in a certain way, just having an innocent instinct and a lot of luck.” So much of Tramp is just a recounting of where that instinct took him.

Hell arrived in New York the day after Christmas, 1966, worked the usual assortment of odd jobs—stock boy, magazine-subscription salesman, taxi driver, mail sorter—wrote poetry, started a small magazine, and got published by New Directions. He plotted his artistic career methodically: Even the tattered, safety-pinned clothes and ragged hairstyles he and Verlaine sported onstage were the result of thorough calculation. “I arrived at the haircut by analysis,” Hell writes, in a typical aside, before going on to riff on the Elvis ducktail, the Beatles bowl cut, and his own shaggy childhood crew cut.

He attracted the right people: Patty Oldenburg, wife of the sculptor Claes, at whose refined hands Hell gained an early sentimental education; a young poet and bookstore owner named Andrew Wylie (Hell dated his sister); Smith, Nicholas Ray, and Malcolm McLaren; Susan Seidelman, who directed Hell in 1982’s Smithereens; Dee Dee Ramone, who became a junk buddy; and Susan Sontag, who did not. He did the right drugs, too—mushrooms, THC, acid, codeine, beer, wine, and whiskey—until he didn’t: Heroin pretty much halts this memoir somewhere in the early ’80s. “The center from which all other paths radiated like a world-sized cobweb,” Hell writes, “was my opiated solitude.”

The gossip here is good, if cruel—Hell, who has himself been a professional writer for more than four decades, still sees fit to settle old scores with fellow musicians, like Verlaine and Smith, and journalists, even dead ones like Lester Bangs. He is frequently unkind. One sentence begins: “Some years later when Kathy Acker wanted me to slap her while I fucked her in the ass . . .”

Mostly, though, you read I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp for Hell’s mind, which is weird and singular and superbly self-aware. He’s a scumbag with an intimate, articulate understanding of scumbag psychology. “Being a rock and roll musician was like being a pimp,” he writes. “It was about making young girls want to pay money to be near you.”

This isn’t nice, but it’s true—something you could say about most of this memoir. Hell is insatiable and insightful, an evil sensualist. “I do love hair,” he confesses, apropos of very little. “Because it’s dead but personal and because I’m moved by the futility of its attempts to warm and protect the places where it grows.” Hell’s gift, then and now, is for finding a redemptive kind of ugly in otherwise blank, beautiful things, himself very much included.

Zach Baron last wrote for Bookforum about George Saunders.