Two rather astute voices were in my ear as I read Megan Hustad’s beautiful but ultimately unsatisfying new memoir: that of the “worker in song” who’s giving Leonard Cohen head in the Chelsea Hotel; and that of Joan Didion, circa Slouching Towards Bethlehem, who delivers a characteristically morbid appraisal of herself, and the rest of us, in “On Self-Respect.”

Hustad’s reminiscence of her lost evangelical youth may seem, on the surface of things, to have little to do with these arch narrations of ingenues gone wrong in the big city. Still, beneath the many broad subjects billed on the jacket copy of More than Conquerors—“class, politics, the slipperiness of memory, the promises of a particular brand of American faith, the seductions of cities, and the chasing of grace in all its guises”—Hustad’s book is really a story of how ambitious and talented young women from the hinterlands are forced to take stock of themselves when they land, bright and big eyed, in New York City.

It’s an old story, a version of the coming-of-age tale previously told by the likes of Holly Golightly and Eliza Doolittle. Either you wake up in this city and accept that personal capital is measured on a different scale here, or you rue the homespun history that sets you at a seeming disadvantage: the kitsch and frugality of midwestern kitchens, the Protestant faith in things unseen, the embarrassment of ill-fitting hand-me-downs, the less-than–Ivy League degree. More than Conquerors is a list of such slights, increasingly whiny as you read on.

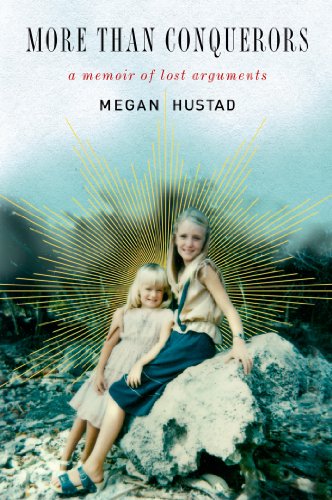

In pieces, the book captures Hustad’s childhood and eventual falling away from her faith and her parents. After a stint working at a high school, her father, Stan Hustad, packs up his wife and two daughters for the Caribbean island of Bonaire, part of the Dutch Antilles. It’s 1978, and Amy, the oldest, is almost nine. Megan is three. They’re MKs—missionary kids—and their family is one of thirty on the island dispatched to operate the evangelical Trans World Radio system.

Even in this unfamiliar setting, commonplace things are imbued with a divine purpose. “The light of a strong clear signal,” Hustad recalls, “was taken as proof that using radio to reach the unchurched was God’s will.” During summertime visits to the States, they ask American church congregations for their keep because Stan doesn’t get paid any salary from Trans World Radio. The restless Hustads move their mission work to Holland in 1983. By 1987, when Megan is twelve, the family is back in Minneapolis, where her father pursues various business propositions and fails at most of them.

Along the way, More than Conquerors attempts to make the case that the girls are disadvantaged by the legacy of their parents’ faith. Thrift-store clothing, “un-American teeth,” a “peculiar accent,” and a Christian past are, we learn, their plight. Years later, while Megan is trying to make it as a publishing assistant in New York, she, Amy, and Amy’s husband, Mark, “agreed that the Hustad missionary upbringing, pleasant tinges of exoticism aside, had generally speaking been bad for us, and further that Midwestern evangelical know-nothingness had deprived us of the launch in life we deserved. You—Mark jabbed a finger in my direction—should have gone to Yale. And that they were too church-minded to see that is unconscionable.” It’s a telling, uncomfortable passage, particularly if you understand that poverty is something other than being deprived of American toiletries or a $58,000-a-year Ivy League education.

Hustad, however, has a couple of key things going for her. She’s the sort of beauty who attracts the kind of men willing to whisk her off to Buenos Aires and buy her three pairs of leather boots, “impractical kitten heel pumps in crocodile leather the color of dried blood,” and a new purse. In any city, that’s impressive. “They’re just things,” she tells him when they learn his apartment has been broken into. Hustad acknowledges that her actions and words are conflicting, but she never spells out just what that conflict means.

The most important thing Hustad has going for her is that she can write. More than Conquerors is embroidered with gorgeous sentences. Of her grandmother during a visit to the mall, she writes, “Marian flung compliments around the way small-town parade marshals threw candy.” While sightseeing with her parents, she observes tourists leaving a bus: “Most paused for a second on the last step to do a 180-degree scan of their surroundings. Only then did they commit to setting foot on the ground.”

The most engaging parts of the book deal with tragedy, such as Amy’s abusive marriage and the death of her great-great-uncle, Peter, in a hunting accident. A cousin, Peter E., stumbles and his gun goes off. “‘Woah, there. Steady now!’ he announced, straightening himself. Then he realized that a significant portion of his namesake’s face lay spattered in the grass.”

These detailed observations carry the book a long way, yet the lack of any arc—the coherence of a family story or a tale of twentieth-century American missionaries—leaves the author’s witty writing hanging. Hustad, like us, closes this book without knowing what she’s worth, without doing an audit of her own character or identifying her value in her chosen context of literary New York.

Which explains why I was thinking about the character of strong, wise women as I read. “We are ugly, but we have the music,” Cohen’s “oppressed” hotel chanteuse tells him, clenching her fist. For good or bad, she well knows what she is and is not. “There is a common superstition that ‘self-respect’ is a kind of charm against snakes,” writes New York transplant Didion, “something that keeps those who have it locked in some unblighted Eden, out of strange beds, ambivalent conversations, and trouble in general. It does not at all. It has nothing to do with the face of things, but concerns instead a separate peace, a private reconciliation.”

Ann Neumann is a visiting scholar at the Center for Religion and Media at New York University and contributing editor at The Revealer, where she writes the Patient Body column. She is currently writing a book about a good death.