In 1962 Diane Arbus asked John Szarkowski, head of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, for August Sander’s address, “because there is something I would like to write to him about.” Several things make this request remarkable. First, there’s the shock that Sander (1876–1964) and Arbus (1923–1971) were even alive at the same time. Then there’s the ordinariness of the proposal, as if an up-and-coming songwriter were casually asking for Bob Dylan’s e-mail. Finally, there is the appropriateness of Arbus’s presumption. Sander’s photographs played a crucial part in the development of Arbus’s mature style, but her work, in turn, is a path that leads viewers back to his—whereupon a Harold Bloom–ish reversal takes place because the Arbus influence on Sander’s work, made before she even held a camera, seems unmistakable.

Szarkowski, of course, knew better. Put in mind of Sander by one of Arbus’s pictures, he pulled out some photographs for her to look at. Not having seen Sander’s pictures before, she was, according to Szarkowski, completely “floored” by them. The epiphany is perfect except in one small detail: It’s not quite true. In 1960, Arbus had dashed off a card to Marvin Israel: “Someone told me it is spring, but everyone today looked remarkable just like out of August Sander pictures, so absolute and immutable down to the last button feather tassel or stripe. All odd and splendid as freaks and nobody able to see himself, all of us victims of the special shape we come in.” Note how Arbus, with the characteristic flash and style of genius, first fixes the Sander style (“absolute and immutable”) before immediately changing that which is immutable into something subtly closer to her own peculiar ends (“splendid as freaks”).

Arbus’s insight was based on only a few of Sander’s pictures; this latest iteration of People of the 20th Century contains more than six hundred of them. Having conceived the idea of a physiognomic portrait of Germany by 1925, Sander photographed hundreds of individuals and families to create “the expression of their time.” He drew on work made as early as 1910 and spent the rest of his life either taking more pictures or reshuffling the results into an order destined never to be definitively achieved. In 1925 he expressed a desire to exhibit the work “as soon as the project reaches some degree of completeness”—and immediately checked himself: “if one can even speak of completeness.” A selection of pictures was exhibited in 1927; sixty were published, two years later, in a book, Face of Our Time. The people in People shifted around, but the overall idea remained pretty stable: an initial portfolio of twelve “Archetypes” followed by seven “Groups”—“The Farmer,” “The Skilled Tradesman,” “The Woman,” “Classes and Professions,” “The Artists,” “The City,” “The Last People”—comprising forty-five portfolios, some of which were subdivided, so that “The National Socialist,” for example, is a subcategory of “The Soldier” within the overall Group of “Classes and Professions.” Since the individuals depicted are types, it is natural to be reminded of Middlemarch and the Reverend Casaubon’s efforts to find and write the “Key to All Mythologies”: the archetypal project doomed by the scale of its ambition. Sticking with photography, we have W. Eugene Smith, whose Pittsburgh Project of the mid-1950s saw him make ten thousand exposures of every aspect of the city before spending years failing to edit the mass of material into some kind of form. Smith eventually came face-to-face with his inability to do justice to “the tremendous unity of [his] convictions.”

Sander experienced his share of frustrations—his work was censored because, in Roland Barthes’s words, the faces he photographed “did not correspond to the Nazi archetype of the race”; his studio in Cologne was bombed by the Allies; twenty-five thousand negatives were lost in a fire in a cellar in 1946—but he seems to have stuck at his “incredible task” with unfailing resolve. People of the 20th Century was not just the work of a lifetime, it was a work with a life of its own, shifting shape to take into account the changing times it sought to preserve. Sander was justifiably proud of the portfolios showing persecuted Jews and political prisoners (including his own son, Erich), which had played no part in his original plans. It is, in fact, Sander’s inability to contain the project within his imposed grid that stops it from being a monument to thwarted ambition, for the thinking behind it now seems pretty loopy. This hard-to-pin-down quality also meant that the project’s intent remained somewhat open to interpretation: While Sander was working, his objectively compassionate amalgam of ideas about types and physiognomies was being turned, with an added racial bias, to darker purpose. (The final Group, “The Last People,” comprises “Idiots, the Sick, the Insane”—among the first to fall victim to Nazi eugenicist policies.) When you consider the way that a picture of a “Turkish Mousetrap Salesman” (!) is included in the “Gypsies and Transients” subsection of “Traveling People” (under the larger umbrella of “Group VI: The City”), the pseudoscientific taxonomy seems more akin to the caste system of Hinduism with its handful of primary social divisions and thousands of subdivisions. And the rigor of the method, it should be stressed, was Sander’s way of pressing his claim to artistic seriousness. In a way that is, depending on your frame of reference, either Hitchcockian or Borgesian (remember the encyclopedia of animals whose categories include animals “that are included in this classification”), a self-portrait of the project’s creator is tucked among the section “Types and Figures of the City.”

[[img]]

So although it is correct that the editors should scrupulously follow Sander’s intentions the way an orchestra aims to be faithful to the score of an unfinished—and unfinishable—symphony, what we are left with is an abundance of photographs that hold our interest in spite of the wonkiness of the immense structure designed to lock them in place. The most common type on offer, it turns out, is the sort whose individuality is revealed most nakedly.

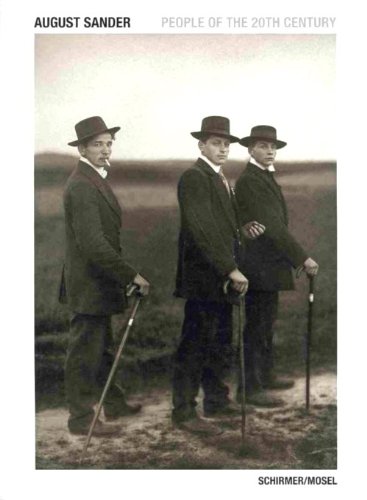

The other irony in so comprehensive a body of work is the way that it has tended to boil down to about a dozen much-reprinted stalwarts: the doughty, bowl-faced baker, the student with his cheeks proudly slashed by dueling scars, the Arbusian blind girls and midgets, the hod carrier with the weight of der Erde on his shoulders, the attorney with his pointy dog (a favorite of Barthes’s), and so forth. And then there’s Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance: Used on the cover of both this volume and an earlier edition published by MIT in 1986, and also the subject of a novel by Richard Powers and a brilliant essay by John Berger, this image has become Sander’s logo in the way that Migrant Mother has come to stand for Dorothea Lange (if not the Great Depression as a whole).

What of the rest? The first thing to emphasize is that there’s so much more to them than faces and bodies. Sander attempted, as Rebecca West said of a compendious effort of her own, “to take an inventory of a country down to its last vest-button.” These vest-buttons—along with cuff links, ties, and boots, together with the buttons, feathers, tassels, and stripes mentioned by Arbus—offer such an abundance of information that Berger, in his essay, concentrates not on the men but on their clothes. For casting directors and wardrobe or set designers on any film set in Germany between the wars, the Sander archive is the first stop—possibly the only one. This is not simply a matter of period detail: Sander gives us the very texture of the times, the psychological cloth from which the Weimar Republic was cut.

What’s surprising is that it’s not only the clothes and hair—which change most noticeably over the years—that seem solidified in the past; the faces, too, are stuck like fossils in the geology of time. People just don’t look like this anymore. There are, at the risk of sounding silly, no proto-dudes or babes here—and this is highly unusual. Look at the portraits Edward Weston made of Charis Wilson in the 1930s: You could fall in love with her today. Going further back in time, a woman I knew at university in the 1970s was amazed to discover that Julia Margaret Cameron had prophetically taken her likeness in 1866. There are, by contrast, only a couple of women in the Sander vaults who look like they could walk around in today’s shoes. The men are identifiably the same species, but the bulk of them look as extinct as mammoths: a negative testament to how thoroughly Sander succeeded in capturing the face of his time. Generally speaking, it’s only the members of the nomadic and racially mixed circus world—particularly the black guy sitting comfortably in his muscled skin and singlet—who could pass as contemporary. In the portfolio of “Artists,” almost none could manage this (the avant-gardists have ended up defiantly behind the times), except, interestingly, Sander himself, who returns the viewer’s gaze as if from across a table, free of the deadlock of old time. In almost every other instance, since the people stubbornly refuse to advance toward us, we have to go back in time to them. Hence, I suspect, the all-consuming psychological pull of the pictures, their immense and draining gravity.

Perhaps that’s part of the reason why the experience of looking at page after page of these faces becomes so oppressive, suffocating, exhausting. It’s a relief to come to “The City” and discover the odd street scene. Further afield, in a monograph published by Taschen, one can take in Sander’s landscapes, trees, and views of Cologne, both pre- and post-bombing. A photograph of the bombed-out remains of his studio serves as a ruined emblem of how badly one craves escape from the density of faces and clothes—of people.

The same urge is subtly satisfied by Michael Somoroff’s profoundly beautiful Absence of Subject (published by Stativ Ltd. in 2011). Somoroff takes some of Sander’s best-known pictures and digitally removes the people from them. Time, at last, has loosened its grip, let them go. But they have, as it were, soaked into their surroundings so that their absence has become entirely present. Where there was once a baker, a pianist, or a family of nine, now, serene and invisibly haunted, there is just a silent kitchen, a vacant room, an empty chair, and grass.

Geoff Dyer’s new book, Another Great Day at Sea: Life Aboard the USS George H.W. Bush, will be published by Pantheon in May.