VERY FEW of Hieronymus Bosch’s approximately two dozen paintings are on view in the United States (and none of his most iconic canvases are), yet the medieval painter’s imagery—at turns naturalistic and bewilderingly hallucinogenic—is broadly familiar, reproduced for High Times illustrations, dorm-room posters, and nearly every time the apocalypse is mentioned. Everyone knows Bosch, but far fewer people have actually seen the paintings in Madrid, Vienna, Bruges, and Lisbon, the locales where the most famous ones reside. Given that reproductions in books are gross diminishments of his sizable works, the massiveness of this tome is a necessary first step toward properly displaying the artist. The volume’s editor, Stefan Fischer, goes further: The book provides complete views of several major works, but the real revelations are found in the reproductions (all newly photographed) of minute areas of the paintings that present scenes much larger than they are on the canvas. A recent discovery that tiny musical notes visible on an obscure figure’s buttocks compose a playable melody testifies to the artist’s desire to fill every inch with meaning. This may be the first time for many of us to actually see Bosch.

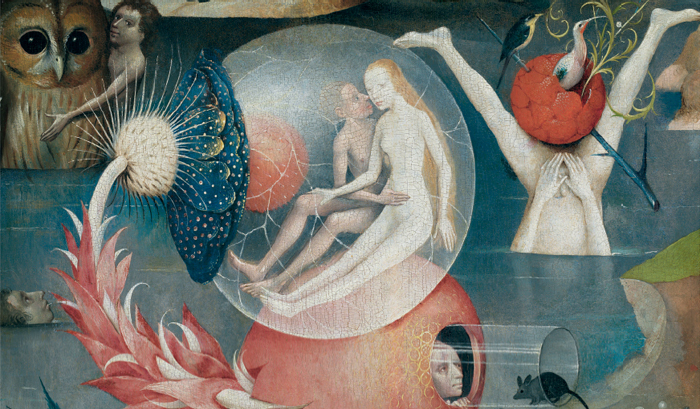

The Surrealists and various other twentieth-century modernists took instruction from Bosch’s visionary inclinations—fantastical fauna, improbable couplings, and oneiric architectures—and doted especially on his depictions of violence and punishment, renderings so intricately devious that they might handily stock a contemporary manual of s/m practices. This appreciation of extravagant elements gave short shrift to Bosch’s spiritual dimension, ignoring how the riotous sodomy, cannibalism, and bestiality all fit securely within religious allegories and scripture. (Fischer offers attentive readings that situate the images within their fifteenth-century political, as well as theological, contexts.) The Garden of Earthly Delights detail above, from the central panel (Humankind Before the Flood),demonstrates the vigor of Bosch’s invention—it’s doubtful anything in the entire oeuvres of Dalí, Ernst, and Tanguy supersedes this dreamscape. Yet there is prescriptive method: The fruit and flowers remind us of the narrative of the forbidden apple and the recent Fall, particularly the trapped man who longingly peers out through a glass tube; the couple above him are sealed within another part of this plant, innocent yet sexual. Probably commissioned in 1503 to celebrate a royal wedding in the Netherlands, the painting can be interpreted as a guide to resisting temptation and making a successful marriage. The density of animistic, biblical, and alchemical symbols puts the viewer in mind of Joyce’s Ulysses, another work besotted with God, the flesh, and the devil. Like that book, Bosch’s paintings require close-up textual study. With these pages, there’s no guard to shoo you back or announce closing time.