LOOKING BACK over the past twenty years of art books, there is much to sift through and much to celebrate. Here, I’ve asked publishers, editors, designers, and booksellers to help me nominate the outstanding titles published in the US during that time. (I limited the search to volumes costing less than $300.)

Today, art-book publishing is blooming in a desert. Despite ever-dwindling nourishment from sales, it is a golden age in terms of both the number of titles available and their impressive quality. No single factor explains this paradox, but if we examine the list, we do see trends. The most important may be the uncoupling of art publishing from trade bookselling. As rising exhibition attendance led to increased in-house book sales, museums and galleries came to regard trade partners as superfluous. Relying on university and specialty book distributors, they began to replace trade houses at the center of art publishing. Relatively inexpensive page-makeup software helped turn books into appealing and versatile vehicles for promotion and marketing as well as creative expression by artists and designers. Traditional forms, like artist monographs and broad art-historical surveys, became rare.

There was little overlap in the lists provided by my twenty-plus respondents—another sign of the wealth of worthy candidates. “20 x 20+” is a nod to Phaidon’s 10 x 10 (2000): As with the other titles selected here, it was not the “best” book of its year, but rather an iconic one—a notable example of the kind of concept book that has proliferated since the mid-1990s. All of the volumes I’ve highlighted below are remarkable for editorial innovation, outstanding illustrations and text, design and production quality, or (not least) success in the market. I could have easily chosen many others, and a more extensive list of the era’s outstanding books is available on Bookforum’s website. Divided into three periods—the first ending with 9/11, and the second with the 2008 economic slump—the list begins, appropriately, with a book about books.

1994–2001

Riva Castleman, who passed away this September, wrote A Century of Artists Books (Museum of Modern Art, 1994) to accompany her final show at the Museum of Modern Art (New York) after three decades of leading the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books. An enthralling look at a neglected aspect of modern art, this catalogue (lucidly designed by Michael Hentges) begins in the 1890s, with Paul Gauguin’s Noa Noa, 1894, and moves up through the early 1990s, when maturing desktop publishing technology and the reduced cost of printing overseas allowed architects, artists, and others to creatively transform art books.

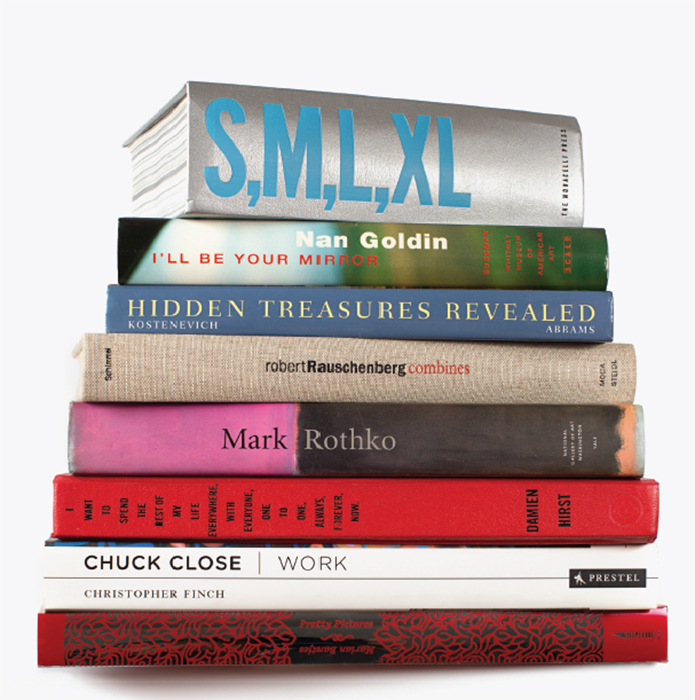

Among the earliest examples of this creative hijacking is S,M,L,XL (The Monacelli Press, 1995). Bruce Mau, the fashionable intellectual’s designer of choice in the ’90s, shared author credit with Rem Koolhaas and the Office of Metropolitan Architecture. Mau made this juiced-up take on the familiar architectural monograph of the ’80s and ’90s into a design showcase: Published just after Koolhaas’s Delirious New York (1994), the 7 × 9" doorstop could have been titled Delirious Design, as it reveled (or perhaps drowned) in the creative possibilities of computer-aided layout. The result is a marginally comprehensible, 1,376-page inundation of words and images. Mau’s studio spawned many talented offspring, including Greg Van Alstyne, who, as MoMA’s chief designer in the ’90s, collaborated with curator Terence Riley on Light Construction (1995), a model of restrained design clarity that is still seen—as is S,M,L,XL—on the desks of student architects.

The fruit of a brief thaw in US-Russian relations, Hidden Treasures Revealed: Impressionist Masterpieces and Other Important French Paintings Preserved by the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, by Albert Kostenevich (Abrams, 1995), was a last hurrah of the high-profile trade art book and a triumph for legendary publisher and editor Paul Gottlieb, who helped sustain Abrams’s dominance of US art publishing in the ’80s and ’90s by partnering with museums to make and promote big, glossy catalogues as part of the “exhibition experience.” Designed by Miko McGinty, the book includes seventy-four paintings that had been in private German collections before World War II, and were then kept in closed storage in the Hermitage after the Soviets whisked them away at the war’s end. Produced under strict secrecy and on an absurdly tight schedule, the book became that rare thing, an art-book best seller, with overall sales approaching a quarter-million copies.

Designed and coedited by Hans Werner Holzwarth, Nan Goldin: I’ll be Your Mirror (Whitney Museum/Scalo, 1996) departs from the still-standard approach of presenting photographs as art objects; instead, the book dispenses with captions and uses frequent single- and double-page bleeds to create an immersive, intimate, and harrowing visual diary–cum–downtown–New York family album. The book opens with four double-page bleeds of Goldin self-portraits in mirrors; the second of these shows her with pearls, lipstick, and two black eyes. Brief texts by her friends include David Wojnarowicz’s aptly titled “Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell.”

Around this time, as museum publishers (kept afloat by exhibition funding) displaced trade ones, the art monograph—traditionally an in-depth account on a “life and works” model of a single artist’s achievement—morphed into a kind of hybrid, an exhibition publication made to resemble a trade monograph that would gradually replace the standard museum catalogue (basically, a guide to the work being shown). Much too heavy to carry through an exhibition, this new thumper gave birth to the exhibition reading room, a stopping point midway through a show where visitors could peruse beat-up catalogues chained to desks. These nicely produced upscale souvenirs usually featured multiple authors in place of a substantial critical text (which harried curators could not be expected to provide). Ellsworth Kelly (Guggenheim Museum, 1997) exemplifies this type of high-quality faux monograph, with a coolly elegant design by Takaaki Matsumoto and fine printing by the German firm Cantz. Another outstanding example, Mark Rothko (National Gallery of Art, 1998), with thoughtful essays by Jeffrey Weiss and John Gage, is printed on silky matte stock, the pages absorbent enough to mute the reflectivity of reproductions that are presented (mostly) one image per spread—all contributing to a contemplative walk-through of Rothko’s oeuvre. It was distributed by Yale, which in 2000 replaced Abrams as the exclusive distributor for the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), a watershed event.

Death, Sex, and Publicity might have been a more economical title for Damien Hirst’s exuberant I Want to Spend the Rest of My Life Everywhere, With Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now (Booth-Clibborn, 1997). But the over-the-top title is of a piece with a book that pulls out all the stops—with tabs that, for example, make a shark disappear and reappear. It features die-cut openings, stickers, spinnable reproductions of Hirst’s spin paintings, and even pop-ups, including one illustrating a preserved bull’s head in a tank. Collaborating with the designer Jonathan Barnbrook and the editor, and now publisher, Robert Violette, Hirst skipped the trouble of convincing a trade house to produce a substantial book signaling his “arrival” in the art world’s upper echelons.

The architecture survey 10 X 10 (Phaidon, 2000) updated the kind of editorial concept book the publisher had had so much success with (e.g., 1994’s The Art Book). Julia Hasting, who became the company’s art director in 2000, added a whiff of design cachet to Phaidon's distinctive Phormula of promotional, impressively plump illustrated titles that had made it the archetypal purveyor of “branded” art books. 10 x 10—in a square format, naturally—features a lenticular cover that alternately reveals and hides the architects’ names as well as those of the critics and curators who chose them. Inside there are bold colors, for example orange and white type knocked out against dramatic black, and a profusion of illustrations that butt and bleed, with practically none of that pesky white space that poky designers used to cherish.

2002–2008

As trade art publishers continued to retrench in response to the post-9/11 recession and drop in sales, and independent booksellers began to evaporate, small publishers started to fill the vacuum: energetic independents, galleries with vision, designers, printers, and others not relying on book sales for income. Jeffrey Fraenkel’s The Eye Club (2003), produced by his San Francisco gallery and named for an informal group of photography experts who, in the 1970s, helped form some of the world’s great photo collections, is an early example of the handsome, gallery-produced or -sponsored books that trade houses now covet. The Eye Club, in quarter-bound black cloth with a surprising mustard-colored cover, is a tour de force: refined design by Catherine Mills and stunning reproductions owed to separations by Robert Hennessey, production by Sue Medlicott, and printing at Trifolio in Verona, Italy.

Accelerating a shift toward books with minimal text and maximal imagery, Matthew Barney: The Cremaster Cycle, designed by Abbott Miller (Guggenheim Museum, 2002), is, like Barney’s Cremaster films, more concerned with mise-en-scène than “plot”—whether biographical narrative, formal analysis, or historical context. Minimal articulation is offered by large, dictionary-like thumb tabs, which allow the reader to navigate from one film’s sea of images—preparatory drawings, visual research, photography, props/sculptures, and film stills—to that of another.

The impact of high-res digital photography on art books is vividly illustrated by comparing two mid-2000s publications devoted to the eternally yoked Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Robert Rauschenberg: Combines (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles/Steidl, 2005) surveyed the artist’s most influential period (1953–64) for the first time, but relied on catch-as-catch-can photography (presumably including transparencies). An attractive package, with cloth binding and a vellum dust jacket featuring an Avedon portrait of Rauschenberg, the volume is marred by washed-out reproductions and mushy details. Jasper Johns: Gray (Art Institute of Chicago/Yale, 2007) fared better, as a private donor made new digital photography possible. Focusing on Johns’s works that employ the color gray—or, more accurately, gray as an abstention from color—it featured an austere cover designed by Roy Brooks, that probably dampened sales, but it boasts reproductions that capture all the richness and subtlety of this far from monochrome body of work. Johns was thrilled.

WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, edited by Connie Butler and Lisa Gabrielle Mark and designed by Lorraine Wild (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles/MIT Press, 2007), is an indispensable reference book that aims to return the achievements of the women’s movement in art to their deserved place at the center of art-historical discourse. The wraparound dust-jacket image, a detail of Martha Rosler’s ironic Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain: Hot House, or Harem (1966–72), is a carpet-like photo collage of nudes cut out from old Playboy magazines that caused more fuss than the show. But the book has its priorities straight: Following 180 pages of plates is an array of concise biographies of international figures, from Magdalena Abakanowicz to the Indian artist Zarina; focused essays by Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Valerie Smith, and others; and a useful chronology of exhibitions.

Chuck Close: Work, by Christopher Finch (Prestel, 2007), a rare example of a single-author critical monograph, was the result of the long friendship between the author and Close. When he was a curator at the Walker Art Center in the late ’60s, Finch helped arrange the first museum purchase of a Close painting, the iconic Big Self-Portrait (1967–68). Designed with trade-book savvy by Mark Melnick, the monograph has gone through two revised editions, each adding new artworks—unlike museum “monographs,” which typically go out of print quickly and are updated rarely.

By now probably more than half the shops represented in Store Front: The Disappearing Face of New York (Gingko, 2008) are gone, victims of Bloomberg-era development. Single-story facades of businesses, captured on lush 35-mm film over a decade by James and Karla Murray (who also interviewed owners and employees), are reproduced in straight-on shots or combined in seamless panoramas of entire blocks, in which urban detritus like passing cars and parking meters has magically disappeared. One of the period’s most successful New York books—an evergreen subgenre—Store Front demonstrated the paradoxical power of digital photo editing to alter actual views in order for us to see more clearly what is really there.

2009–2014

In the work of Jeff Koons, scale and execution are everything, so Jeff Koons (Taschen, 2009), with its immensity, skillful “curating,” and spare-no-expense production, trumps the recent Whitney exhibition publication, though their structures are similar. No account of recent art publishing would be complete without attention to Taschen’s flamboyant strategy of making oversize, limited-edition monographs, boxed and signed, as well as an even more exclusive “art edition,” packaged with an original artwork, followed in a year or two by a trade edition sold at a reasonable price. With luck, the special editions recoup the publication’s costs, and the trade version is gravy.

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (2011) benefited from a perfect storm—the suicide of the couturier maudit, a sensational exhibition, and a knockout cover: a lenticular image of McQueen’s head morphing into a metallic skull. Here we see the triumph of fashion as art, with high-profile “visual culture” replacing art history as the tailor’s dummy, so to speak, on which art books are shaped. 2011 turned out to be a banner year for Met publishing; the press also received Best Book honors from the Islamic Republic of Iran (an award bestowed by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad) for The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp: The Persian Book of Kings (2011; both Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale), published to celebrate the opening of the Met’s Islamic galleries. A collaboration between the Met and the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, this sixteenth-century illustrated manuscript of the poet Firdausi’s Shahnama, the Persian national epic, brings together in one volume miniatures scattered across many collections.

Marian Bantjes Pretty Pictures (Thames & Hudson/Metropolis Books, 2013) is a self-made monograph by the Vancouver virtuoso of computer-assisted illustration and design. The imposing (14-inch-tall) book, every detail of which the obsessive Bantjes looked after, combines mind-numbing complexity with psychedelic sweetness—a volume to get lost in. The clever cover of Kara Walker: Dust Jackets for the Niggerati (Gregory R. Miller, 2013), produced with the design firm COMA, unfolds into a large artwork that includes Walker’s foreword and a full-scale detail of one of the show’s ink-transfer-on-paper text pieces, And Modern Black Identity, 2010. Walker’s work has inspired a number of inventive books and catalogues, beginning with a pop-up artist’s book in 1997 and including the Walker Art Center’s reading-book-format retrospective catalogue, Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love (2007), whose cloth cover is embossed with a bold text: “Dear you hypocritical fucking Twerp . . .” Walker conceived Dust Jackets’ images as “potential covers for unwritten essays, works of fiction, and missing narratives of the black migration,” transforming the art book from coffee-table objet to conscience catalyst.

Art Spiegelman perfectly captured the contradictory urge of the marginalized artist—outsider, graffiti writer, fashion designer—to be part of the art-history game but also thumb his nose at it from the sidelines in Co-Mix: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps (Drawn & Quarterly, 2013), which he created for a traveling survey. With a trim proportional to standard tabloid dimensions, the better to evoke an alternative newspaper or broadsheet, it features a tipped-in comic-book insert (“Two-Fisted Painters”) and several handsome gatefolds. Lastly, Contemporary Chinese Art, by Wu Hung (Thames & Hudson, 2014), is a possibly unique example, in recent years, of a trade publisher bringing out a classic, comprehensive survey of a body of modern art by a single author who is a recognized eminence in the field. Weighing in at 456 pages—and an unusually hefty list price—it will, I hope, become available in a more affordable format and enjoy a long, multiple-edition life.

TRADE PUBLISHERS with deep backlists will carry on and small publishers will continue to proliferate. Just over the horizon, as yet with no consumer base, electronic art publishing promises a new form of interactive visual experience, untethered from a turn-the-page format and exploiting the dynamic potential of databases running on cell phones and tablets. Just as computer-aided design and digital image editing empowered artists, designers, and small publishers, so too may modestly scaled, cloud-based technology help small presses circumvent the bully Amazon (as well as the more benign distributors that dominate art publishing). For the moment, print art books remain among the most consistently beautiful commercial objects produced by our culture—not to mention our most reliable form of long-term visual-information storage (remember CD-ROMs?). And they are great bargains: A hardcover book that sold for $65 in 1994 ought to cost almost $100 now, given the rate of inflation, but that book will still probably sell for $65 and its reproductions will be much better. Many of the books mentioned here are out of print but readily available online and from used-book sellers at modest costs. They are hidden (in plain sight) treasures.

Bookforum thanks the following contributors for their suggestions: David Anfam, Phaidon Press; Susan Bielstein, University of Chicago Press; Jamie Camplin, Thames & Hudson; Roger Conover, MIT Press; Mary DelMonico, DelMonico-Prestel Books; Daniel Frank, Meridian Printing; Thomas Frick, freelance editor; Sean Halpert, Museum of Fine Arts (Boston); Hans Werner Holzwarth, Hans Werner Holzwarth Design/Holzwarth Publications; Christopher Hudson, Museum of Modern Art (New York); Stephen Hulburt, Prestel; Norman Laurila, MoMA; James Leggio, Brooklyn Museum; Laura Lindgren, Laura Lindgren Design; Miko McGinty, Miko McGinty, Inc.; Mark Melnick, Mark Melnick Graphic Design; Judy Metro, National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC); Abbott Miller, Pentagram Design; Lisa Pearson, Siglio Press; Mark Polizzotti, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York); Terence Riley, Keenen/Riley Architects; Gwen Roginsky, the Met.

Christopher Lyon is an art-book publisher in New York.