Kathy Acker met media theorist McKenzie Wark in 1995, when Acker was on tour in Australia. A novelist, essayist, and performance artist, Acker first made a name for herself in the New York art world of the 1970s, achieving widespread notoriety in 1984 when a mainstream press published the thrilling, anarchic novel Blood and Guts in High School. Acker was widely regarded as both inheritor and innovator of the literary avant-garde, and like many of her later books, Blood and Guts in High School appropriated text and themes from classic works, filtering them through the voices of multiple narrators—who often resembled the author and in some cases even shared her name. As her friend Avital Ronell wrote, “she didn’t turn her back . . . on the literary tradition”; she turned the literary tradition on its back. She brought to her relationships the same force she brought to her work. Whatever it was—a book, a room, a party—she always made it her own.

Her final novel, Pussy, King of the Pirates (1996), would be published shortly after Acker returned from Sydney, where she and Wark had a brief affair. When she returned to the States, they corresponded via e-mail, exchanging more than a hundred pages’ worth of messages in a few weeks, which are now collected in this volume. Each one is prefaced by the date, time, and subject, as well as the e-mail addresses it’s been sent from and to: a deceptively banal format for anyone who isn’t tempted by the prospect of reading other people’s e-mails. For those who are, the layout is immediately alluring, and the book will not disappoint, especially if one is an Acker fan. The collection does nothing so routine as “revive” her reputation. Rather, it makes a figure with whom we’ve grown familiar seem strange: It offers a new light in which we might read her work, and it brings to her new life.

The courtship documented in the book seems at once urgent and protracted: Often one of the correspondents sends four or five e-mails before the other replies. Multiple conversations are maintained, initial responses returned to and elaborated on. They occupy each other’s imagination, and become—more than merely thought of—that which directs and inflects the other’s thoughts.

They disclose assorted details about their daily lives (messy apartments, hangovers, parties), discuss their work (Wark’s first book, Virtual Geography, had come out a year earlier; Acker was collaborating with the Mekons), and tell stories about their friends. Books, TV, and movies are important tokens of intimacy. They pool and reflect on shared references (Nietzsche, The X-Files), make recommendations and take them (Blanchot, Pasolini), and read in and out of step with one another. They also talk about sex and relationships, including past affairs and—especially in Wark’s case—current partners.

In many ways, I’m Very Into You resembles much of Acker’s other work, at least thematically. It is, at its core, a study of power and sex, and of performance, how we invent ourselves through our relationships with—our stagings of ourselves for—other people. “You know I’ve been working hard for your friendship, Ken,” Acker writes. “I have about a hundred cats living in me and all of them are curious. So in order to talk about you, I get to ask questions.” One is about their encounter in Sydney (why didn’t he touch her the last night they slept together?); in his response, Wark reassures her: “I really liked sleeping with you. Really.” He adds that he’s been working hard to be her friend, too, “like I’ve been chattering away. . . . It’s like getting the rhythm to a waltz right. Only who’s gonna lead? Does it always work that way? Is there always a butch/femme moment in every exchange?” Acker picks up this thread later and echoes a version of his question back to him: “Like . . . when we e-mail. . . . who’s taking the lead?” There’s no “who’s gonna lead,” Acker senses. Someone has already taken it.

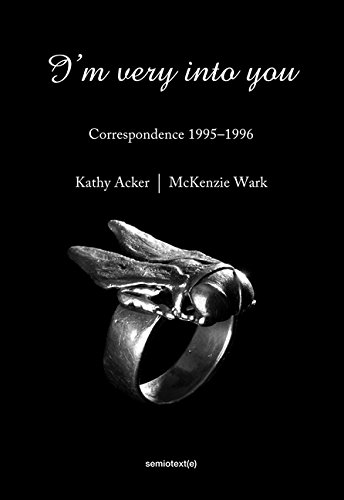

[[img]]

Who that is becomes clear when Acker invites Wark to stay with her for a night while he’s traveling. He accepts casually, telling her he can take care of himself if she’s busy. “I’m not fucking playing games,” she responds, and says her apartment “isn’t a hotel.” He’s the one with the power—the one who wasn’t sure, initially, if he wanted to go to her reading, to meet her, to do this thing. It’s cool to talk about his girlfriends and all, but, Acker writes, “fucking just tell me what you want and I’ll go with it. That’s what you do when you do s/m scenes. . . . If you don’t discuss the rules, then the shit power games are outside the bed and they hurt. And I’m truly no longer interested in either hurting or being hurt.” He apologizes, but she’s still bruised by the exchange. By the confusion she felt—a by-product (or main product, possibly) of the standard heterosexual seduction ritual, with all the artful ambiguity it requires. For the rest of the correspondence, her guard isn’t what you’d call up, but it’s never as down as it once was. She keeps writing—but then she keeps apologizing, too.

Throughout their correspondence, Acker and Wark discuss subject position and sexual identity, often raising the questions in the abstract—how does one seduce, or behave when seduced—in order to further seduce each other. The urgency that particular discussion had, in this particular cultural moment in the art and literary worlds of the mid-1990s, is especially palpable in these instances, as Acker recognizes her role in their relationship—and, by the same turn, that their exchange is the very thing it’s about. (In other words: You’re never just e-mailing about your life. You’re living it.) Understandably, she resents having to “rise up to the surface, through the codes of irony I learned to play in England, and ask you directly ‘What’s going on?’ Seemed a bit brutal to have to do that.”

What seems equally brutal, if not more so, is a passage that comes earlier in the book, just a few days into their correspondence. In it, Acker responds to an e-mail from Wark about how Australia imagines—is infatuated with—American culture: “We can never be AmeriKKKa but we can do it in drag! We want Gidget! We want Bob Hope!. . . . We want Kathy Acker!”

“Oh Ken,” she replies:

the KATHY ACKER that YOU WANT (as you put it), is another MICKEY MOUSE, you probably know her better than I do. It’s media, Ken. It’s not me. Like almost all the people I know, and certainly all the people I’m closest to, all of whom are “culture-makers” and so-called successful ones. . . . We’re hustling, we’re doing the two-step. . . . Our only survival card is FAME and the other side of the card, the pretty picture, is “homelessness”. . . . No medical insurance; no steady job; etc. This isn’t me, Ken, or rather it is me (personal) and it isn’t: it’s social and political.

I’m Very Into You is the autobiographer’s autobiography, letters from the person who lived inside—and through—the persona generated by her writing and solidified by her celebrity. It’s a useful complement to the “I” of her fiction—that near-mythic “I,” one often produced by laying texts side by side or by channeling other voices, the text acting as a psychic medium. It’s a testament to the formal qualities of e-mail, the way it summons us to ourselves—to reveal exactly who we believe ourselves to be, one human being addressed to another. These e-mails trace, too, what e-mail was and has become, and how we’ve been accustomed to the medium and molded by it. Our patterns of expression, our expectations, even the rhythm of our thoughts: The cadence of Acker and Wark’s writing foretells our own. In the essay “Writing, Identity, and Copyright in the Net Age” (1995), Acker describes this process, identifying it as a model not only of intimacy but of intellectual exchange: “We need,” she wrote, “to remember friends, that we write deeply out of friendship, that we write to friends. We need to regain some of the energy, as writers and as readers, that people have on the Internet when for the first time they e-mail, when they discover that they can write anything, even to a stranger, even the most personal of matters.”

By the time Acker met Wark, perpetuating an image was her primary means of income. “Can’t figure out why I’m doing this,” Acker writes to Wark on a night she’s “flipping out” with desperation: “I tour . . . like . . . every month and am more than used to the nature of the life.” It’s not your typical Kathy Acker scene. Most of the scenes in I’m Very Into You aren’t. In these e-mails, Acker writes about feelings—and with them—that she didn’t, or couldn’t, approach in much of her published work or in her public appearances. Maybe she would have, eventually, but then it was a fragile hold on security being “Kathy Acker” gave Kathy Acker. She was diagnosed with cancer in 1996, shortly after the last e-mail in the collection was sent, and passed away in 1997. No cushion, no time to rest—no health insurance. It must have seemed a bit brutal. It still does.

Elizabeth Gumport is a writer living in New York.