There’s a shorthand phrase in Israel for describing the politics of war and peace that permeates everything: ha matzav, “the situation.” You might come upon a conversation between two people and ask, “What are you talking about?” And the response would simply be “the situation.”

This can mean whatever happened that morning—a café blown up, olive trees vandalized in the occupied territories, or the latest proclamation of “Death to Israel” from Tehran. But it can also capture the particular flavor of a collective existence that finds itself, on a regular basis, trounced by History—an unrelenting, never-forgotten force, as much a part of everyday life as whether the buses are running or it’s rainy outside.

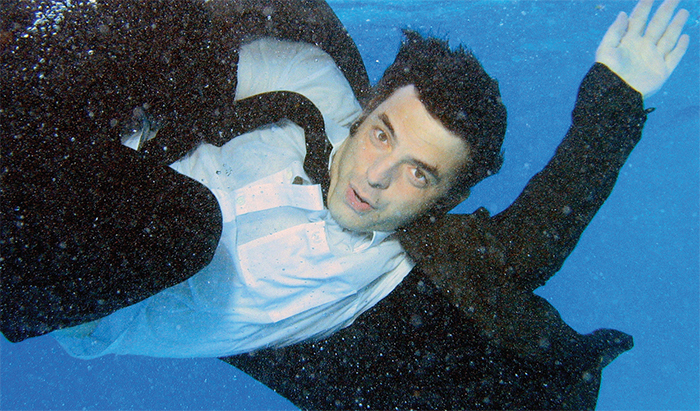

Etgar Keret, the most internationally celebrated and widely read of his generation of Israeli writers, has been notably uninterested in “the situation.” His microstories are no longer than a couple pages each and don’t concern themselves much with Hezbollah or Netanyahu. The best of them are fantastical and arrive, very economically, at some strange wisdom about the inner life of the human animal.

To take a few examples from his last story collection translated into English, Suddenly, a Knock on the Door (2012): In “Lieland,” a man discovers a secret gumball machine granting him entry into a world populated by characters he has invented in the lies he has told since childhood (e.g., the made-up sick uncle, the made-up injured German shepherd he said he had to stop and rescue) and must come to terms with the misfortunes he has inflicted on them. In “Unzipping,” a woman discovers a small zipper in her boyfriend’s mouth that allows her to zip off his skin and reveal another man inside. (“A teensy zipper. But when she pulled at it, her whole Tsiki opened up like an oyster, and inside was Jurgen. Unlike Tsiki, Jurgen had a goatee, meticulously shaped sideburns, and an uncircumcised penis.”) The story ends a few paragraphs later with the woman finding her own hidden zipper and wondering if she should pull it.

This is crystallized absurdity. When these stories work, they’re irresistibly charming—parables that, if not as obviously profound, have as much power as Kafka’s, told with the vertiginous insight of a man who’s observing the world while standing on his head. But sometimes, when they don’t work, they can feel like Israeli twee: a little too precious and emotionally cute. (Unsurprisingly, Keret’s stories are regularly featured on “This American Life” and have been the source for many an earnest film student’s first short.) They never really get all that dark, bitter, or difficult—and should they start to, the white space marking the end of the story is never far off.

All of which makes his latest book, The Seven Good Years, a striking departure. It’s a memoir, and a highly personal one, that covers the period between the birth of his son, Lev, in 2005, and the death of his father from cancer, in 2012. In that span, Keret becomes an adult. He confronts the strange new vulnerability of having a child and tries to acclimate to the existential loneliness of losing a parent. In one of the later vignettes, after his father has died, Keret injures his hand while cushioning his son’s fall after he slips on a wet bathroom floor. Lev wants to know why his father sacrificed himself. “The world we live in can sometimes be very tough,” Keret tells his son. “And it’s only fair that everyone who’s born into it should have at least one person who’ll be there to protect him.” If there is an emotional arc at the heart of the sometimes scattered material of The Seven Good Years, it’s somewhere here—in Keret’s discovery that he’s that person for his son, and in his loss of the one person who was that for him.

The Seven Good Years is also, inevitably, about “the situation.” Keret repeatedly invokes the helplessness of a parent trying to protect his child in an environment that feels constantly menacing. Deprived of the luxury of escaping into fantasy and of indulging a rapid pivot into the next story’s magical situation, involving, say, talking fish, Keret is forced to examine the anxiety of living in his particular society much more directly than he does in his fiction. This comes through, for example, in his description of playground debate with a group of mothers about whether he will let three-year-old Lev join the army when he grows up, and in a scene in which he decides to stop washing the dishes or taking out the garbage after becoming convinced that Iran is close to lobbing a nuclear bomb at Tel Aviv.

Indeed, “the situation” is as inescapable in the pages of Keret’s book as it is in Israeli life. Some of the episodes Keret recounts take place on his travels to book festivals and readings in places like Sweden and Indonesia. At one event, in Sicily, Keret looks out at the Mediterranean Sea, a body of water he knows very well. Except from Sicily it seems different, somehow: “The same sea, but without the frightening, black, existential cloud I’m used to seeing hanging over it.”

After years of reading Keret stories in which “the situation” only intrudes when the sound of a radio-news announcer’s voice comes wafting through an open window, I found it refreshing to see how central the conditions of Israeli life are to his work and his thinking. His alertness to the way people navigate their relationships with each other—an attribute that exists in something of a vacuum in his stories—widens here to include his own relationship to the Israel that surrounds him. It’s a place where parents need to make up a game called “Pastrami” to get their children to lie down on the side of the road when an air-raid siren goes off. A place where a customer-service representative will yell at you for trying to lower your cell-phone bill with this retort: “Tell me, sir, aren’t you ashamed of yourself? We’re at war. People are getting killed. Missiles are falling on Haifa and Tiberias, and all you can think about is your fifty shekels?”

Keret is a sketch artist. He makes no excuses for this. He gets great joy out of his own style of writing, as he tells Miranda July in the brief Q&A that serves as a preface to this book, and he has never seen any reason to listen to anyone who told him that he should “write differently.” This commitment to the sketch as an art form suffuses this memoir, too. Perhaps because he’s attempting a sustained portrait of himself, the fragmentary quality of The Seven Good Years feels frustrating in a way his stories usually don’t. The various episodes of his life he describes don’t seem chosen out of an attempt at self-examination—the hard work that makes the best memoirs so good. Instead, they seem triggered, as one imagines his stories are, by a funny or bizarre incident with some twist that leaves a bittersweet feeling, the easy trace of a smile on the reader’s face. This is not to say The Seven Good Years avoids real emotion. Particularly at the end, as he’s slammed by the reality of his father’s death, Keret confronts devastating grief without the comforts of cuteness.

Though Keret has distinct limits when it comes to capturing the bruising rigors of real life, he also appears, to his great credit, to understand this. The most revealing episode in the book doesn’t have to do with his father or his son or “the situation.” It takes place at a reading at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. Keret, the most accomplished of three writers reading one evening, agrees out of “either generosity or condescension” to go last. The first writer leaves him impressed, but the second absolutely floors him with an anecdote that delves deeply into moral questions, ones only a writer can plumb, in this case via a story about a father whose children are spending their summer vacation torturing animals. Keret is shaken by it, and as he walks past the writer to the podium, he observes, “She gave me a pitying glance, the kind a proud lion in the jungle gives to a circus lion.”

The other writer grasped something Keret says he himself had forgotten: that it is a writer’s job to draw on the darkness and ugliness of his or her own life to explore difficult human questions, to tiptoe along that moral line that demarcates right from wrong, civilization from chaos. The only kind of writer who forgets that his vocation is to navigate this difficult territory, he writes, “is a successful one, the kind who doesn’t write against the stream of his life, but with it, and every insight that flows from his pen not only enhances the text and makes him happy, but also delights his agents and his publisher. Damn it, I forgot it. That is, I remembered that there’s a line between one thing and another, it’s just that lately, it has somehow turned into a line between success and failure, acceptance and rejection, appreciation and scorn.”

Etgar Keret seems, after all, the kind of writer not completely content just to be that charming circus lion.

Gal Beckerman is the author of When They Come for Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).