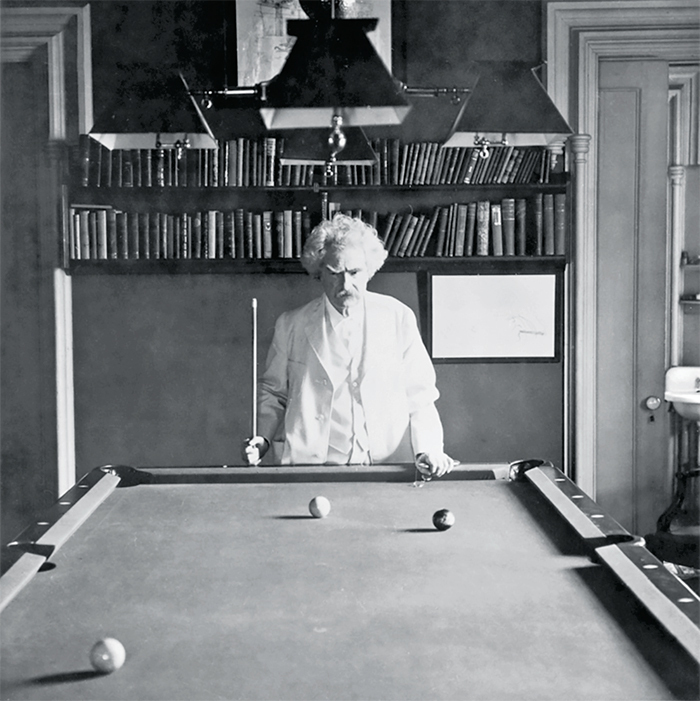

Mark Twain was at the peak of his fame when a London club granted him an honorary membership. Told his only predecessors were two explorers and the Prince of Wales, he sized up his own inclusion nicely: “Well, it must make the Prince feel pretty fine.” The planet’s most celebrated American author until Ernest Hemingway came along—and guess whose laurels have proved more durable?—Samuel Clemens was never one to take a backseat to anybody. No wonder, then, that he seems much more himself as the undisputed star of Chasing the Last Laugh, Richard Zacks’s entertaining account of the international lecture tour Twain undertook in 1895 to pay his debts after his unfailingly disastrous business sense had brought him to the brink of ruin, than he does getting second billing to diplomat John Hay—once Abraham Lincoln’s baby-faced private secretary during the Civil War—in Mark Zwonitzer’s The Statesman and the Storyteller. Because Zacks’s concept is a lot simpler, his book is the shapelier of the two, mining contemporary accounts, the Clemens family’s letters, and Twain’s own writings to craft a lively tale that might as well be called Around the World in 800 Days.

But Chasing the Last Laugh is still a minor addition to the vast Twain literature, while Zwonitzer has produced a jam-packed, engrossing epic of American political and diplomatic history in what Thomas Beer memorably named the Mauve Decade. In fact, Zwonitzer’s main miscalculation isn’t demoting Huckleberry Finn’s author to supporting player but trying to make too much of him, even though Twain’s role is bound to attract readers who don’t know John Hay from Johnny Ramone.

Zwonitzer’s idea is to make Twain, who lived mostly abroad (in London and Vienna) for several years after his world tour was done, a sort of long-distance Banquo as the country Hay served discovered the rapacious joys of going full-on Macbeth in the 1890s and early 1900s. Having run out of home continent to conquer, the US briskly got busy annexing Hawaii, vexing the British Empire with its new virility, beating the pants off Spain in “a splendid little war”—Hay’s own mocking description, meant to deflate his undeflatable future White House boss Theodore Roosevelt—and subjugating the Philippines after vague promises of independence. By way of lagniappe, we built a humdinger of a navy and the Panama Canal.

Transforming America’s global role in roughly a decade, this sudden spree of chess played with blackjacks is largely forgotten now, since the fabled innocence America is forever losing depends mightily on a talent for amnesia. Yet Zwonitzer’s chronicle of aggressiveness fig-leafed by piety makes George W. Bush and Dick Cheney look like amateurs compared to the phlegmatic, privately fretful, but imperium-seduced William McKinley. And McKinley, in turn, comes off as an imperial dilettante compared to his brash young vice president, Teddy Roosevelt, who vaulted to the top job after McKinley’s assassination in 1901. The upgrade, if anything, calmed Teddy down, but he remained a cheerful berserker when it came to any policy designed to extend America’s imperial reach.

No jingo himself—or at any rate an uncommonly civilized and hence elusive one—Hay was probably the most capable and effective secretary of state in US history. And that was very much what he needed to be, regardless of how you may come down on the overseas empire that sprang into being while he handled the mellifluous parts of the job. We do know what Twain thought of it, since the rampant butchery and torture of our Philippines counterinsurgency drove him to a rare break with his habit of never doing anything to risk his popularity. That’s the admirable but uncharacteristic episode that apparently tempted Zwonitzer to aggrandize Twain into Hay’s full-time foil.

After startling New York society with a 1900 speech that went off-topic to decry “sending our bright boys out there to fight with a disgraced musket under a polluted flag,” Twain castigated the whole enterprise, and imperialism in general, in “To the Person Sitting in Darkness.” Unlike most of the diatribes indicting Christianity, militarism, and “the damned human race” he scribbled in his later years, this one was meant for public consumption, earning Clemens brickbats once it was printed early the next year in the North American Review. By contrast, “The War Prayer”—today probably the best known of Twain’s antiwar polemics—stayed unpublished until after his death in 1910.

How important were Twain and Hay to each other? Not terribly, no matter how hard Zwonitzer—who’s much too scrupulous to fudge things outright—works to link them. Twain had befriended Hay and praised his poetry during the (slightly) younger man’s literary phase. While seldom meeting in person, they exchanged the occasional cordial letter until Hay’s death in harness in 1905. Yet it’s worth noting that Hay’s name doesn’t crop up at all in Chasing the Last Laugh, which examines approximately the same years of Twain’s life through a less politicized lens than Zwonitzer’s.

Try as Zwonitzer might, the Twain-Hay relationship finally seems too tangential to either man’s CV to justify The Statesman and the Storyteller’s ambitious scheme of depicting their career arcs contrapuntally. That’s especially true because the one event that would give it a dramatic point—an open break between them over US policy—never occurred. Even when Clemens was fulminating publicly and privately against McKinley’s and then Roosevelt’s “skull and cross-bones” version of the Stars and Stripes, his old acquaintance the secretary of state was conspicuously exempted from his anti-imperial broadsides.

For that matter, Zwonitzer can hardly disguise the fact that venting about public affairs was a fairly incidental sideline compared to Twain’s main concerns at the time—or at any other point in his career. In both these books, Twain is primarily dealing with the chaotic fallout from his failed publishing company and dim-witted investment in an unworkable typesetting machine with eighteen thousand moving parts. His prime objective late in life was getting his finances back on an even keel by peddling his wares both onstage and in print, while also coping with the tragedy of his daughter Susy’s death from meningitis at age twenty-four. Since Zwonitzer’s structure obliges him to keep switching between Clemens’s and Hay’s situations anyway, that makes for a few too many vapid segues on the order of “Sam Clemens wasn’t keeping close tabs on geopolitical events at the beginning of June 1897.” You don’t say.

Unexpectedly, readers may find themselves groaning each time they turn a page to see they’re in for another well-wrought but otiose chapter about Twain’s pecuniary and domestic troubles in another foreign domicile. We want to get back to the good stuff: the contending agendas and vainglorious personalities of Zwonitzer’s fabulous gallery of Washington pooh-bahs and New York press barons; the mordant contrasts between the urbanity of drawing-room imperialism and its brutality in frontline close-up; Hay jousting with foreign plenipotentiaries and preening US senators to turn blueprints into realities—if not vice versa, since negotiating treaties is often a highly retroactive art form.

Zwonitzer handles all this material superbly, giving us a cornucopia of social and atmospheric detail without losing sight of the big picture. At a time when the US State Department got by with fewer than eighty overburdened Washington employees, the men (which they all were) in the higher councils of government—including the Senate, not yet elected by popular vote—were a tightly knit clan of elitists on intimate terms with one another who didn’t put much stock in democratic nostrums. The serene clubbiness of it all makes our latter-day establishment seem raffish by comparison. Hay himself hadn’t held an official position in thirty years when McKinley brought him back into the game, initially as our ambassador to the Court of St. James before a reluctant Hay got talked into becoming secretary of state, a job he predicted would kill him in six months. (It didn’t.) But it didn’t matter, since he knew everybody anyway, from Henry Cabot Lodge—his tormentor on the Senate floor at least once—to, of course, TR. “Hay needed no office in order to wield influence,” his longtime friend Henry Adams wrote, sounding a bit nettled by the fact. “For him, influence lay about the streets, waiting for him to stoop to it.”

Zwonitzer deploys his glittering cast to near-novelistic effect. Adams, predictably, is always good for a jaundiced remark—one that’s usually brainy as well, except when he’s quoted parading his unembarrassed and vicious anti-Semitism. Lodge struts the stage like a peacock trapped in a falcon’s body. Effortlessly crowding Twain aside, however, the book’s real supporting MVP is Teddy Roosevelt—“clearly insane in several ways,” in Clemens’s own appraisal, but nonetheless a man no writer has ever managed to make dull. TR seems to have left everyone in Hay’s circle aghast, but not appalled, and you can’t help thinking that maybe it should have been the other way around. Zwonitzer’s description of TR’s elaborate demurrals regarding his pursuit of the No. 2 spot on the 1900 ticket is very funny—“There is no instance of an election of a Vice President by violence,” Hay tartly told him—and so is Hay’s bemused recollection of hearing Roosevelt speak French: “It was absolutely lawless as to grammar and occasionally bankrupt in substantives, but he had not the least difficulty in making himself understood, and one subject did not worry him more than another.” That was more or less the man’s whole approach to life in a nutshell.

As for the big picture, it gains considerable freshness from Zwonitzer’s use of Hay as his primary vantage point. There’s nothing like a born negotiator pressing nonnegotiable demands and doing it skillfully enough to keep his opponents’ pride intact, only to have to start over when Capitol Hill’s grandees decide the result is insufficiently obnoxious and braying. Even Hay’s years as our ambassador to Britain add fascinating grist to the mill, because our new overseas assertiveness had already been redefining us as the British Empire’s upstart competition and—surprise, surprise—the Brits were hardly unaware of it. Hay’s finesse goes a long way toward explaining why their reaction wasn’t more truculent.

By the time The Statesman and the Storyteller wraps up, the writing is already on the wall so far as future US supremacy goes. Not only have the British grumpily acceded to the Panama Canal, but we’ve also made a smashing success of bloodily crushing the Filipino insurrection while Britannia is botching the Boer War. There’s something almost poignant—but not quite—in how the young Winston Churchill (aka their Teddy Roosevelt) pops up for a cameo toward the end, welcomed to New York by Twain with a barbed encomium on Anglo-American relations: “Now . . . we are also kin in sin.” Obviously, to plenty of patriots who don’t fit the Fox News definition of one, the saga of our superpower origins is no triumph; it’s a horror story. By and large, Zwonitzer keeps his own indignation tempered—meaning that he doesn’t waste time berating people as interesting as Hay or even Lodge for being ignorant of twenty-first-century values. Even so, it isn’t just to amplify Twain’s disgust that we’re given so much eyewitness testimony about the squalid—and officially sanctioned—cruelties of the Philippines campaign. “You have no idea what a mania for destruction the average man has when the fear of the law is removed,” one young soldier wrote home. “I am in my glory when I can sight my gun on some dark skin and pull the trigger.”

That quote doubles as one of Zwonitzer’s many reminders that the whole project was rooted in an unabashed conviction of racial superiority. After all, our conquest of the Philippines was what inspired, if that’s the word, Kipling’s atrocious but catchy propaganda poem “The White Man’s Burden”: “Ye dare not stoop to less,” and so on. (Give the men of one African American US Army unit credit for making the perfect joke when jeeringly asked what “you coons” were doing so far from home: “We have come to take up the White Man’s Burden.”) Even Hay, not given to crudeness, was prone to calling Central American nations “dago countries,” which can only mean that, in his circles, such talk wasn’t considered crude. The book’s saddest passages are those describing the Filipino emissaries who couldn’t get a hearing for their increasingly desperate—but outdated—appeals to America’s own founding ideals.

Call me gutless, but I admit it: Despite my overall admiration for Zwonitzer’s several-hundred-page plunge into Mauve Decade imperialism at both its suavest and its most barbaric, Chasing the Last Laugh came as something of a relief. For one thing, I needed a Twain fix that Zwonitzer—who’s ultimately not that interested in him as either a literary figure or a showman, only as a scourge and/or martyr—hadn’t provided. Because it suits Zwonitzer’s scheme, The Statesman and the Storyteller dramatizes Twain’s world tour largely as an ordeal, goaded by dire necessity and full of setbacks, stress, and mishaps. Without ignoring the tsuris, Zacks is much more alert to the pleasure that Twain gave his far-flung audiences—not something to deprecate, since that was the point—and how he went about providing it.

If you only know Twain’s stage routines from Hal Holbrook’s egregious Mark Twain Tonight!, Zacks’s absorbingly detailed reconstructions of his performances—the carefully honed timing, the shrewdly reworked and reshuffled greatest hits—will increase your appreciation of him as a showbiz craftsman. The literary truism that Twain the entertainer betrayed Twain the artist began within his own family—“He should show himself the great writer that he is, not merely a funny man. Funny!” Susy lamented—but it’s worth remembering that their idea of great writing was the now all but unreadable Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. Anyone with an investment in pop culture should mistrust the idea that being a crowd-pleaser corrupted Twain’s genius; rather, it was an emanation of it.

Besides its credible and vivid portrait of Twain, the book is also a very enjoyable travelogue, because the English-speaking world’s colonial and semicolonial enclaves as the nineteenth century waned were fascinatingly variegated societies. Each one seemed to bring out different facets of the touring guest of honor’s personality. If Twain was unexpectedly, and charmingly, smitten with India, despite any misgivings he might have had about the Raj’s inequities, so is Zacks; he packs page after page with the flavorful marvels he’s culled from the writings of Twain and others. When politics crops up, as it inevitably does—journalists were always quizzing Twain about the issues of the day—Zacks makes it clear that Twain was a) no savant and b) out to protect his brand by muzzling his crankier opinions most of the time, as when he evasively (but maybe accurately) told one Aussie reporter, “I haven’t a bit of political knowledge in my stock that is worth knowing.”

Whether real or feigned, that kind of ignorance has generally been a source of pride to later generations of American literary luminaries, who’ve followed Twain’s example in railing against our superpower atrocities, from Vietnam to Iraq. Setting the pattern we’re still familiar with today, his public opposition to imperialism was valiant, eloquent, bracing, morally unimpeachable—and had zero effect on the outcome. Maybe he didn’t recognize it, but his real contribution was to comfort everyone who was as horrified as he was by letting them know that at least Mark Twain was on their side. In a convoluted way, he was still in the business of cheering people up.

Tom Carson is a freelance critic and the author of Gilligan’s Wake (Picador, 2003) and Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter (Paycock Press, 2011).