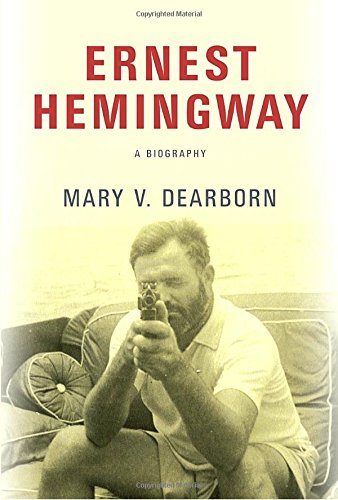

The unusually striking photograph on the cover of Mary V. Dearborn’s new biography Ernest Hemingway shows the writer in his prime in 1933 sitting on the cushioned stern of a boat, possibly his thirty-eight-foot cabin cruiser the Pilar, and aiming a pistol at the camera. He always carried guns on board to shoot sharks or, when bored or annoyed, seabirds and turtles. He was thirty-four when this photo was taken and he had recently discovered Key West and the fabulous Gulf Stream with its gigantic marlin, sailfish, and tarpon. He fished and fished and fished, insatiable. There were the heroic fighting fish, the trophy fish—some of which he used as punching bags after they were strung up on the dock—but all provided pleasure. When a colorful school of dorado appeared on the surface around the Pilar, Hemingway and his party landed eighteen of them in five minutes. They’d be used as fertilizer for his wife’s flower beds. He referred to this time, the decade of the ’30s, as his “belle epoque,” for there was not only the happy scouring of the Gulf Stream, but also the hunting in Wyoming for elk and antelope (for lighter fare he shot prairie dogs from a moving car) and the safari in Africa, where lions, leopards, cheetahs, and oryx could be collected, though it rankled him when others killed bigger animals than he did, or those with darker manes, bigger racks, or, in the case of rhinos, larger horns.

“I like to shoot a rifle and I like to kill and Africa is where you do that,” he said.

But killing could be fun anywhere. In Sun Valley, Idaho, he and two of his young sons, Gregory and Patrick, visiting from school, shot four hundred jackrabbits during one adventure. Years later, another son, Jack, would reminisce that “one of the most memorable moments of my lifelong relationship with my father” took place in Cuba on the roof of the Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s home there, where they drank pitchers of martinis and shot “great quantities of buzzards.” The highlight for Patrick, “the last really great, good time we all had together,” was “dropping hand grenades on turtles” from the deck of the Pilar during the bizarre sub-hunting days of the ’40s, the acts “justified by the need to learn how long it was between when you pulled out the pin and when it went off.”

It is said that Hemingway never killed an elephant—he admired their fidelities and social structures apparently—but his youngest son, Gregory, the “troubled” child, the son who after several wives and eight children underwent sex-reassignment surgery and died in a Florida jail as “Gloria” Hemingway, shot eighteen elephants in a month. It’s possible he shot them to annoy his father, whom he considered a “gin-soaked abusive monster,” but he also claimed it was just damn relaxing to kill elephants. The activity made him less anxious about things.

Gregory wrote a book about “Papa.” So did his half-brother Jack. So did Hemingway’s brother Leicester, and Hemingway’s fourth wife, Mary. In his younger years he was quite charismatic and people who knew him then remembered that and wrote about it. The bulls, the booze, the fresh air, the slopes, the streams and war stories. And many other books have been written about Hemingway—there is Carlos Baker’s chummy hagiography; Michael Reynolds’s deep life; Jeffrey Meyers’s woundy thesis, the one that bothered Raymond Carver so; Paul Hendrickson’s spirited, speculative boating party; James Mellow’s scholarly and overblown production (“He had been at the center of a cultural revolution unequalled in its wide-reaching effects on Western culture except by the Italian Renaissance . . .”); Kenneth Lynn’s psycho-hugie; Peter Griffin’s focus on the early, enchanted, good-looking days. Even so, it’s been fifteen years since we’ve had a major new study of the man. But now, with Dearborn’s grimly astonished book, we do.

One approaches the life of Hemingway not with excitement but with an anxious defensive duty. After all there are a great many writers who learned a great deal from his work—the early work always—the cleanness of the line, the freshness, the solemnity of the sentence, the discoveries that restraint and omission allow. Gertrude Stein said that he looked like a modern but smelled like a museum. I don’t smell museum. The word that springs to my mind is fetor. The stench of death. Hemingway stared death in the face again and again and was proud of it, but it was almost always an animal’s death, an animal’s face, a creature’s face, the face of a nature he repeatedly diminished, the light and life of which he would extinguish over and over.

He killed far more in life than he did in fiction, obsessively, methodically, in the sanctified slaughter referred to as sport.

An acolyte said he could be forgiven anything because he wrote like an angel. But during the last long years of Hemingway’s life, the angel had pretty much left. Perhaps the last time the angel was truly in the building was 1936, when Esquire published “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” It was a good story. Somewhat self-regarding and sentimental, with the little plane and all. Pretty ending, though: the grinning pilot, the cold clean peaks.

As the work became less good, the life became more bloated. There was just the killing and the pomposity and the betrayals and foolish exaggerations and gleeful cruelties. And still, he continued to be forgiven a great deal.

For true aficionados, it is the writer’s work, and only the work, that matters. And this is appropriate and correct. But biographers—it is a dictate of their profession—focus on the life. If legend has overtaken the life, so much the better. A decision was made, possibly by Hemingway himself as his great gift shrank and his powers lessened, that it was his life that was singular, that it was the artifice of life that would endure. The critic James Wood has said that Hemingway “preceded his own bad influence,” that he was the “master of his wake,” that he “franchised” himself. This has continued through the efforts of his publisher, Scribner, and the estate. His only surviving child, the octogenarian Patrick, when asked if he still read his father’s work, allowed that he did because he had “a commercial interest” in being “competent in the marketing of it and the management of it.” Back in the ’90s, Patrick and his brothers, who were still alive, threatened to sue Key West (which just wants to have an eternal good time) over the popular and rowdy Hemingway Days party in July. They wanted it to be a “more dignified” gathering. They also wanted royalties. It was just in 2012 that Scribner reissued A Farewell to Arms with its forty-seven possible endings. (Still a relief to know he chose the best one, the walking-out-in-the-rain one . . . ) A Scribner publisher said, “This is one of the most important authors in American history and fortunately or unfortunately you need to keep refreshing or people lose interest.”

A Farewell to Arms (Hemingway considered other titles, such as Death Once Dead, Of Wounds and Other Causes, and In Praise of His Mistress) was written in 1929, and despite fluffing and refreshing efforts remains uncanonized. As is the case with For Whom the Bell Tolls, which is so melodramatic and antique—“Did thee feel the earth move?”—as to be mostly unreadable today, though when it was published in 1940 it was an enormous best seller.

The decade of the ’40s saw no new fiction from Hemingway, though he remained keen on the ranking and reputation of others. Regarding his dead friend F. Scott Fitzgerald’s posthumously published The Last Tycoon, Hemingway wrote that he was awfully “glad it got such a fine, prominent review in the New York Times Book Review,” but “the book has that deadness . . . as though it were a slab of bacon on which mold was grown. You can scrape off the mold, but if it has gone deep in the meat, there is nothing that can keep it from tasting like moldy bacon.”

With his new, third wife, the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn, he traveled (“China by way of Hollywood”), wrote some journalism, honed his tall tales, hunted for Nazis on the heavily armed Pilar, spied for the Soviet Union (code name Argo), and enjoyed his new fiefdom in Cuba, a fifteen-acre hilltop retreat overlooking Havana. By 1946 he had shed Martha for Mary, who fit more or less seamlessly in to the good times at the Finca and as the last of his wives was to see Hemingway through to the bitter bitter end.

In 1950 the disastrous Across the River and into the Trees was published. It was Hemingway’s worst novel. The love story is embarrassing, the prose execrable: “Now, beating up the Canal, against the cold wind off the mountains, and with the houses as clear and sharp as on a winter day, which of course, it was, they saw the old magic of the city and its beauty.” The year 1950 also saw Lillian Ross’s bizarre and damaging New Yorker interview with Hemingway, “How Do You Like It Now, Gentlemen?,” in which he imagines himself boxing with the greats. “I started out very quiet and I beat Mr. Turgenev. Then I trained hard and I beat Mr. de Maupassant. I’ve fought two draws with Mr. Stendhal, and I think I had an edge in the last one.” He modestly allowed he was not quite ready to get in the ring with Mr. Tolstoy.

Mr. Faulkner, however, was another matter. When Faulkner won the Nobel in 1949 and produced his famous speech about man not only enduring but prevailing, Hemingway said: “He made a speech, very good. I knew he could never, now, or ever again write up to his speech. I also knew I could write a book better and straighter than his speech and without tricks or rhetoric.” From the lengthy unfinished manuscript of his Sea book, he salvaged the story of the fisherman Santiago, which was published as The Old Man and the Sea in 1952. Two years later he won the Nobel and gave a rambling victory speech before a few friends and journalists at the Finca: “I am a man without politics. This is a great defect but it is preferable to arteriosclerosis. I like the fighting cocks and the Philharmonic Orchestra. . . .” And so on. He prepared a more eloquent statement later for the ceremony in Sweden, which he did not attend.

The fattest prize of all did nothing to assuage his fear and loathing of younger writers who dared to struggle for ascension. He particularly detested James Jones’s From Here to Eternity. He wrote to his editor that maybe he should reread it, but: “I do not have to eat an entire bowl of scabs to know they are scabs; nor suck a boil to know it is a boil.” It was around this time too that he wrote a threatening letter to Cardinal Spellman (of all people) recounting a “story about being constipated as a boy and subsequently plugging up a toilet at a track meet.”

Hemingway was becoming even more unhinged (though it must be said he had always enjoyed writing nasty letters). Although he puttered about the Finca shooting off a pair of miniature cannons he’d ordered, traveled to Spain for more bullfights, fell in love with a teenage Italian girl and then with his young secretary Valerie (who later became one of Gregory’s four wives), and motored about in the Pilar bemoaning the fact that the Gulf Stream had been fished out, he was increasingly feeling “dead in the head,” no doubt because of the five concussions he’d suffered over the years. (In the last one, the result of a plane crash during his final African safari, cerebral fluid leaked out of his skull.) Mary complained of his drinking and his “endlessly repeated aphorisms” while he complained of the bad dreams he had at night and the bad dreams he had in the day. (Though one earlier had been pleasant enough: He had made love to a bear and they shook hands afterward.) Cuba wasn’t enjoyable anymore. Nothing was enjoyable. It was thought a return to the American West might be salubrious. They bought a house in Idaho, in Ketchum, a concrete-bunker-like affair with enormous plate-glass windows overlooking a river. It was certainly private. Hemingway was becoming increasingly paranoid and depressed, delusional, almost mute. His mental and physical descent into the maelstrom could be conducted pretty much out of the sight of old pals and sycophants, both his cuadrilla and the critics.

It’s unknown who took the first steps in addressing Hemingway’s mental illness, but some eight months before his suicide in July of 1961, he was taken to the Mayo Clinic

in Rochester, Minnesota, and given a series of shock treatments. He was admitted under the name of George Saviers, his “country doctor” in Idaho. Inexplicably, the Mayo team pronounced him cured, his confusion and depression the result of medications

he was taking for physical ailments—mild diabetes and liver disease. There is no record that he was given any antidepressants or antipsychotic medicine.

Our biographer, Mary V. Dearborn, spends little time on the final months and days. “It did not end well,” begins the final brief chapter. Dressed in the red Italian bathrobe that his wife called the Emperor’s Robe, Hemingway, early on that summer morning, took the key to the gun case that was left on the windowsill in the kitchen, went to the foyer, chose a shotgun, and blew his head off. Certainly one would think that a key to the gun case so brightly visible, so practically shrieking its encouragement, would be less available. . . . But no matter. Hemingway was through. And there was no way it could possibly end well.

Dearborn does not bury Hemingway in this six-hundred-plus-page biography, but she doesn’t resurrect him either. Her portrait is solid, sympathetic, and direct. She does not struggle for his relevance. The relevance is, to her, a given. Hemingway “changed the way we think, what we look for in literature, how we choose to lead our lives.” And, the biggest canard of all, because of his “intense feeling for the natural world,” he taught us about the natural world.

This is from the book’s peculiar prologue, in which Dearborn attempts to explain why she’s taken on the project in the first place. It seems to have had something to do with a Hemingway program some years ago at the Mercantile Library, where a member of the audience wanting very much to share addressed the panel: “I just want to say that Hemingway made it possible for me to be who I am.”

What could this possibly mean? I don’t know. But Dearborn finds it terribly important, even though, she writes, “it was difficult to determine the speaker’s gender, only that it appeared to have recently changed.”

So is Hemingway ushered, somewhat muzzily, into the new century.

Martha Gellhorn said of Across the River and into the Trees that it had “a loud sound of madness and a terrible smell as of decay.” But this was just a book, only words on a page after all. The real smell of decay, the fetor, came from the life. Again and again, he had taken from nature. He killed everything and anything he could in all seasons without qualm or restraint with an obsession bordering on the insane. Nowhere has it been suggested that Hemingway ever felt remorse for all the killing or felt an urge to conserve the species and wild places he so “loved.”

No one knows what he saw in his bad waking dream that July morning when he found and held the little key. Maybe he saw a monstrous pile of fin and wing and horn and heads and hides, rotting radiant piles of his slaughtering. And maybe that alarmed and saddened him. Or maybe not. At the end he seemed mostly worried about taxes.

The Hemingway House in Ketchum, Idaho

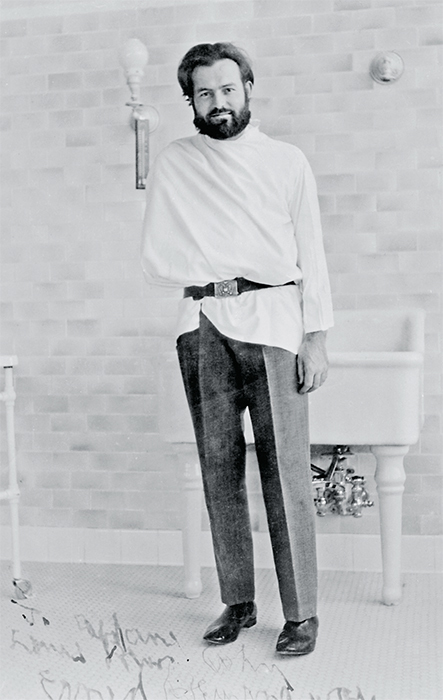

A WEALTHY TIN HEIR and bon vivant, Bob Topping built the house in Ketchum in 1953 for his fifth wife, an ice-skating intructess at the Sun Valley Lodge. He built it to resemble the lodge from which he had been ostracized, perhaps because of his relationship with the instructess who was twenty-five years younger than he. He exits history in 1959, when he sold it, mostly furnished, to the Hemingways. It’s a perfect example of midcentury modern, blond within and rather cold, its fabulous views now compromised by the million-plus-plus-plus-dollar houses on the other side of the Big Wood River. The closets still hold Mary’s colorful dresses, many with dry-cleaning tags from the ’70s, but there is little of Hemingway’s . . . aura. At most, he spent around six months in the house, though he’d been visiting the area for years, and by all accounts was sick, unhappy, and frightened here. He found the landscape too quiet and lonely to be out in it. The typewriter is not his, nor are most of the books. (He had left thousands behind in Cuba.) In the stairwell, there is an unsettling painting, by his friend Waldo Peirce, of two men skinning a decapitated bull. There’s the famous photo portrait by Yousuf Karsh—the one with the turtleneck—over the mantelpiece, and another casual photo of Hemingway adjusting the thermostat, sporting the caption “Civilians! Do you want lovin’ heat or eatin’ heat?” (Who knows if he actually said that, of course . . . ) There are several of his many many traveling trunks, and some jokester (a former caretaker perhaps) has placed a red towel monogrammed papa in the tiled (seafoam) bathroom. Once a big-screen TV hung from the ceiling in the living room. He saw Jimmy Stewart accept a special award for his ailing friend Gary Cooper at the Oscars ceremony in 1961 and, urged on by Mary, called him afterward. “Bet I make it to the barn before you do,” Cooper said, and he did, dying of prostate cancer in May, seven weeks before Hemingway’s suicide. For five years, Mary maintained that it was an accident, that he died cleaning his gun. As a widow, she lived primarily in New York City but used the house sporadically until her death in 1986, changing only the entryway. In a rather ironic turn, she bequeathed the property to the Nature Conservancy. At almost fourteen acres, it is the largest holding within Ketchum city limits. Twelve years ago, the Conservancy floated the idea of leasing the house to the Hemingway Foundation, which would open it to the public and give tours, but the neighbors—inhabitants of the million-plus-plus-plus-dollar houses nearby—went apoplectic. (Someone must have had the traumatic experience of visiting the Hemingway house on Whitehead Street in Key West, the one touting the fraudulent six-toed cats.) The Nature Conservancy has now turned the Ketchum property over to the town’s marvelous Community Library. The library, which is on excellent terms with everyone, at least so far, plans on opening up access a bit but hopes to run it mostly as a residency for scholars and writers. Hemingway is buried in the Ketchum graveyard, along with Mary and a constellation of others, friends and family, including even Gloria.

Joy Williams’s most recent book is Ninety-Nine Stories of God (Tin House Books, 2016).