The narrator and (barely) protagonist of Lynne Tillman’s smart and sleightful novel—her first since American Genius, A Comedy (2006)—is one Ezekiel H. Stark, a cultural anthropologist who specializes in vernacular photography. He’s a playful invention, given to citing highbrow or avant-garde culture—“We worked in silence. John Cage scored with it.”— and then undercutting himself with passé slang: “Kidding. Not.” In his earnest, academic, sometimes awkwardly demotic fashion, Zeke outlines his personal-professional interests in self and image, the inward oddness of family life, and wider cultural movements, chief among them second-wave feminism. He also sketches a sort of method. “I’m telling you that I’m telling you; my self is my field, and habitually I observe, and write field notes.” Over the four hundred pages of Men and Apparitions, Zeke is by turns analytic, emotional, distanced from his own tale, and immersed in others’ histories. In the absence of any dominating narrative line, he is exhausting his stock of images, anecdotes, and essayistic digressions on the history of private image-making. And he is hinting at—flagging but refusing to speak directly about—his current work in progress, an ethnographic study of the attitudes of men his age to women and to feminism: “I was a new man among new women, and we new men needed help, and Zeke to the rescue.”

Zeke was born in 1978, so is old enough to recall the aesthetic and affective pull of analog photography, and young enough to be in thrall, like the rest of us, to digital images. In either era, as Zeke contends from inside his battery of antique theory, “an image is a concoction, often manufactured, meant to create a way to be seen, viewed, understood. It can be aerie faerie, a phantom, phantasm.” It’s a way of thinking about representation that privileges the vagrant, fleeting, and ambiguous. The question is: Are Zeke’s critical resources up to the job of understanding real bodies, real presences? The reference points for his disquisitions on images, family, and memory are familiar—including Roland Barthes and photo historian Geoffrey Batchen—though Zeke has catholic tastes in photography, and also remarks in passing on Stephen Shore, Susan Hiller, and Gerhard Richter’s Atlas, among others. But it’s the domestic snapshot that interests him most, that maybe keeps him at some remove from the actual subjects in those images, and has brought him to his present pass as an assistant professor with hopes of tenure, embarking on a “field study” he calls MEN IN QUOTES.

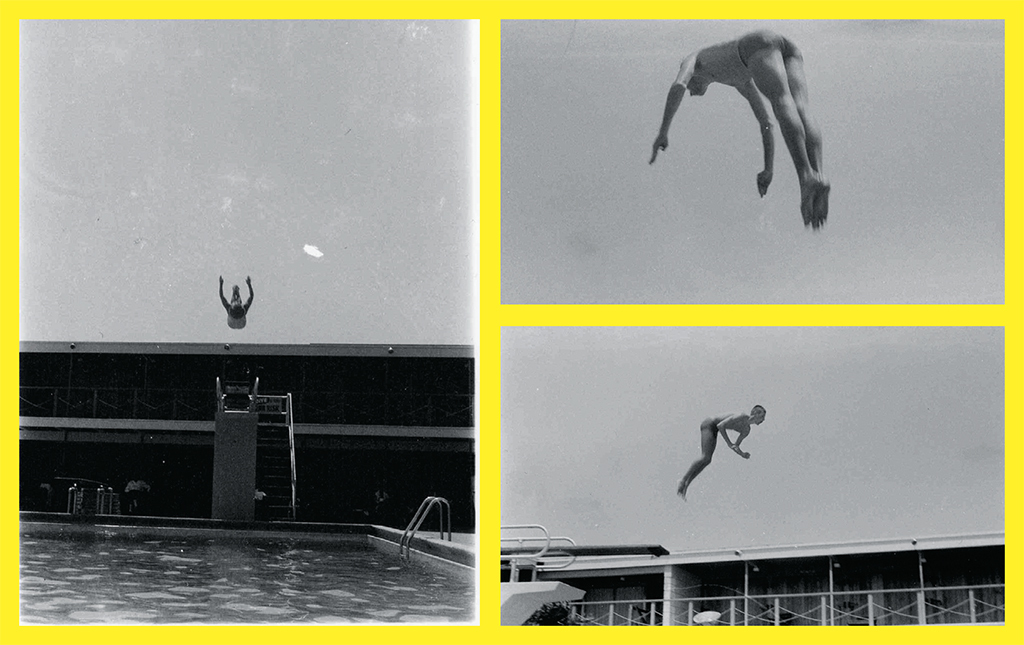

Eventually we’ll get a précis of this project, followed by an excerpt: The former oddly pitched and partial, so that we may wonder—as Tillman no doubt wants us to— about Zeke’s chances before a tenure committee. In the meantime, however, he is busy making us doubt his grasp of, or commitment to, the role of participant-observer in the field where he has made his name. On the one hand, he is suspicious about the veracity of the images in front of him, which are drawn from his own family inheritance and random junk-store acquisitions. (Tillman punctuates, and sometimes fills, her pages with these grainy black-and-white pictures.) On the other, Zeke constantly undercuts his own scholarly self-consciousness: “Whose ‘I’/‘eye’ can be trusted? From what I learned in my family, I don’t trust anyone in front of or behind a camera, but I keep my bias out of it. Kidding.” That “kidding” is a tic in Zeke’s monologue, an intentional irritant in Tillman’s construction of him that means we’re never sure how capable he is of the task before him: making sense of his family history via photographs.

That history, as with most families, is both of its time and out of it, symptomatic and particular. Zeke grew up outside Boston in “John Updike territory. Nice family place, if you didn’t know the family.” His father was a lawyer and a drinker, his mother a freelance editor—“mater of grammar, fact finder”—marked but not exactly liberated by feminism. (“Mother trotted from room to room, brain ON, tight-lipped, but her body wasn’t. As part of her boundlessness, she discussed issues with me as if I weren’t a kid.”) The three Stark children have been subject to a florid array of diagnoses: Zeke’s sister was mute, and his brother “is just a pathologist who suffers from what psychiatrists call taphephobia: he’s totally afraid of being buried alive. No one knows why.” And Zeke’s analyst tells him he has abulia: “an abnormal lack of ability to act or make decisions.” In some respects there is an orthodox novel of late-twentieth-century American family life lurking inside Men and Apparitions, but the novel is more essay collection than cross-generational saga. As Zeke puts it, “In childhood, desires and passions are seeded. In adulthood, they flower into interests and manias.” (As a child Zeke is obsessed by insects—he keeps a pet mantis called Mr. Petey—and by photography; he learns to order the world from “a super-charged madman high school biology teacher, Mr. Church.”) Something like this happens to the narrative premise of Tillman’s novel, which quickly bristles with essays and riffs and gobbets of criticism that sound and don’t sound like a twitchy cult studies prof with concentration problems.

They sound more like Lynne Tillman, at least in the slantwise irony of voice and the teeming richness of Zeke’s interests, his manic attention to art, literature, ideas, and the representative detritus of (mostly) American life. You could read Men and Apparitions as something like a scrambled sequel to its author’s most recent essay collection, What Would Lynne Tillman Do? (2014), such is the variety of its fleeting subjects. There are passages and pages here devoted to Pierre Bonnard, Clifford Geertz, Vermeer, Gertrude Stein, the rise and fall of Polaroid, Warhol’s Screen Tests, Alice Miller’s Drama of the Gifted Child, the murder of JonBenét Ramsey in 1996, and the final episode of Six Feet Under. Most of this constellating of culture is sharp and sharply expressed, but Zeke is sometimes behind the curve: He thinks the internet has killed TV drama, and his twentieth-century models for image critique have not caught up with grammable reality.

At thirty-eight, Zeke suspects the culture has outrun his academic assets. He’s of an academic generation—maybe just a generation—that found it easy to leave behind the more pressing exigencies of identity politics for aestheticized melancholia and regret, assuming the present would not violently intervene again. Hence, obliquely, a long section of Tillman’s novel devoted to the life of Marian “Clover” Hooper Adams: nineteenth-century photographer; socialite; associate of Emerson, Hawthorne, and Thoreau. Adams is one (privileged) model from the deep cultural-political prehistory of a feminism that marks a modern male American life like Zeke’s: She’s the New Woman who will eventually make the New Men he’s interested in studying possible. Zeke is indebted to and shaped by women like her in ways he has only begun to grasp. He’s interested in how his historical cohort of men relate to women and think about the politically charged period that came just before they were born. Men and Apparitions ends with sixty pages of Zeke’s MEN IN QUOTES, a part-oral-history account of present American male attitudes—for which, according to her acknowledgments page, Tillman solicited and quoted responses from numerous men. For example, a man referred to as “Subject 17” says, “The dignity of women is important to me. . . . But I’m not beyond being covetous, sexually insensitive, and objectifying.”

How are we to take these passages, with their pleasing assertions of gender parity and occasional admissions of discomfort or failings with the specifics of same? The answer depends partly on how seriously we have been able to take Zeke and his scholarly sublimations of familial trauma. Also on how far we can credit the recuperation of the “New Man,” once a staple cliché of mainstream media and now a historical curio, a comic vision of what masculinity might have been like after second-wave feminism. (If there’s a visual shorthand for just how crudely this figure was drawn in pop culture a quarter of a century ago, it’s in various images of muscled bros holding babies.) Can we have actual new men, or was the possibility shut off decades ago by the cartoonish, ironic image of the New Man? Tillman’s choice of a thirty-eight-year-old guy as the anxious medium by which to pose this problem is a canny and prescient one, in light of recent revelations about harassment and abuse by men young enough (or is it old enough?) to know better. Think how many of these men have claimed, implausibly, that their crimes and misdemeanors occurred in unenlightened times, now past. Think how often you’ve found yourself asking: What, the 1990s? Or the 2000s? Among its many other wise and witty lines of thought, Men and Apparitions is a vexing inquiry into the recent sexual-political past. Zeke’s ethnographic coda asks whether his generation of educated men, with their keen sense of aesthetic complexity and lingering family trauma, are best or worst placed to help point the way beyond it.

Brian Dillon’s Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction will be published in September by New York Review Books. He is UK editor of Cabinet magazine, and teaches writing at the Royal College of Art, London.