Near the end of Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood recalls how her mother, mortified by Esther’s recent stay at an asylum, recommended they simply carry on as if nothing—the fits, the hallucinations, the suicide attempt—had ever happened. “Maybe forgetfulness, like a kind of snow, should numb and cover them,” Esther thinks. “But they were part of me. They were my landscape.”

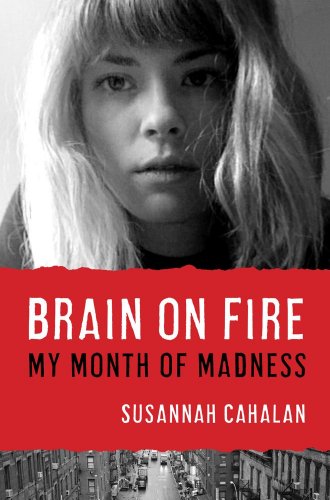

Unlike Esther, New York Post reporter Susannah Cahalan says she remembers almost nothing of her terrifying brush with madness, but she’s no less haunted by it. Using evidence gathered from interviews, medical records, journals, and hospital video cameras, she delivers an intense, mesmerizing account of survival in her new book, Brain on Fire.

It all began in early 2009 during New York’s bedbug scare, when Cahalan says she woke up one morning with “two red dots on the main purplish-blue vein” of her left arm. That evening, after a day at the Post where she uncharacteristically spaced the “impossible to forget” weekly pitch meeting with her editors, Cahalan was struck by a sharp pain in her head “like a white hot flash of a migraine.” A few days later, she found herself snooping through her steady boyfriend’s emails, suddenly and inexplicably paranoid over his exes.

This was all a prelude to the tempest building in Cahalan’s brain. A few days later, her left hand went numb. Then she began losing her short-term memory and hallucinating. Finally, the seizures arrived. “Though I had been gradually losing more and more of myself over the past few weeks, the break between my consciousness and my physical body was now finally fully complete,” she writes. “In essence, I was gone.”

Before it was over, she would miss seven months of work and rack up one-million dollars worth of medical bills.

Like a good thriller, Brain on Fire’s mercury quick chapters race through this mystery, gradually revealing Cahalan’s scary, disorienting illness. Ten days after her first blackout, she was admitted to NYU’s Langone Medical Center where she spent twenty-eight days in the hospital’s advanced monitoring unit. “I wish I could understand my behaviors and motivations during this time,” she says, “but there was no rational consciousness operating, nothing I could access anymore, then or now.”

Perhaps the only thing worse than being diagnosed with a serious affliction is being seriously afflicted and undiagnosed, so one of the book’s most rewarding moments is when Cahalan finally receives hers. After hundreds of neurological exams and some absurdly expensive treatment—at one point, for instance, Cahalan receives a series of intravenous immunoglobulin infusions, each of which “cost upwards of $20,000”—the author learns she is the 217th person worldwide since 2007 to be diagnosed with anti-NMDA-receptor autoimmune encephalitis.

Essentially, this means that an autoimmune disease compromised the ability for the neurons in Cahalan’s brain to talk to one another, silencing essential conversations that “are at the root of everything we do.” Although she’s mostly recovered today, she now talks in her sleep every night, and when she compares pre- versus post-illness photos of herself, she sees “something altered, something lost—or gained.”

Despite its grave subject, Brain on Fire is never maudlin. Cahalan punctuates the narrative with comic moments that arrive via her college buddies and her colorful colleagues, the “slingers of hyperbole” at the Post. One of them, a Wiccan priestess who works at the paper’s library, tries to help Cahalan by giving her a tarot reading early in the book. But things still feel off the next day. “It’s probably just residue from the astral travel you experienced during the reading we did yesterday,” the woman says, “I think I may have taken you to another realm.”

The book also chronicles the particular way tragedy can bring people together. Cahalan’s devoted boyfriend, for instance, earns the nickname “Susannah whisperer,” and there are several wonderfully tender moments between Cahalan and her father. One night, he steadfastly refuses to leave his daughter alone, even after she has reduced him to tears during one of her psychic fits. Later, she tells us how he “bumrushed” a young doctor for telling a group of students – in front of her – that she may need to have her ovaries removed.

Cahalan’s deft descriptions of her spooky hallucinations could be right out of a Poe terror tale. Here, she walks past framed headlines in the halls of the Post before her seizures begin: “The pages were breathing visibly, inhaling and exhaling all around me. My perspective had narrowed, as if I were looking down the hallway through a viewfinder. The fluorescent lights flickered, and the walls tightened claustrophobically around me. As the walls caved in, the ceiling stretched sky-high until I felt as if I were in a cathedral.”

Perhaps the scariest thing that emerges in Brain on Fire is a clear picture of how deeply flawed our medical industrial complex is. Cahalan suffers through misdiagnosis after misdiagnosis during her treatment, partly because her disease is extremely rare. In one instance, a rushed doctor, “a byproduct of a defective system that forces neurologists to spend five minutes with X number of patients a day to maintain their bottom line,” simply doesn’t listen to her.

That doctor “is not the exception to the rule. He is the rule,” she writes. “I’m the one who is an exception. I’m the one who is lucky.”

John Wilwol has reviewed for The Washington Post, the San Francisco Chronicle and NPR.