Is it true that everyone remembers the day death was first explained to them? I was seven and a hamster had died. The hamster had been given to me, perhaps, so that it could die and facilitate the conversation I then had with my mother. I remember not wanting to pay too close attention to what my mother was defining for me, so I listened instead to the faint sound I heard coming from downstairs. It was my father playing a record. I strained to make out the lyrics of the song and realized that, by doing so, I could somewhat ignore the words my mother spoke. This was the first moment of what would become a most useful skill—the ability to divert focus from what is the front-facing reality: that my life, all life, is meaninglessly short.

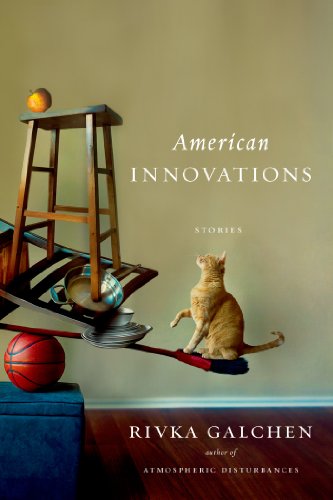

Rivka Galchen’s approach to life and death is an epistemological one. Central to American Innovations, Galchen’s new collection, is this question: How might we keep ourselves from knowing the only thing we could know—that life is unavoidably marked by losses big and small until all is lost, completely and totally? Dead fathers, distant mothers, truant husbands, and disappearing friends populate the backgrounds of Galchen’s stories. These abandonments are met not with the protagonists’ contemplation, but with their dogged avoidance.

Accordingly, “The Lost Order” begins by telling us what is not happening. “I was at home, not making spaghetti,” the narrator explains. She glosses over the fact that she’s left her job, and only hints that her husband is being unfaithful: He’s misplaced his wedding ring; he is urgently telling her he loves her on the phone. The points are quickly dodged and, instead, we receive the inner ramblings of the newly stay-at-home wife, interrupted by an odd call from a man who has mistaken her phone number for that of a Chinese take-out restaurant. Her failure to fulfill his request for the speedy delivery of garlic chicken is something she allows herself to feel guilty about, while weightier problems lurk at the periphery. Similarly, in “The Entire Northern Side Was Covered with Fire,” a novelist avoids learning why her husband has abruptly left her and their unborn child, though the answers may be readily available in the husband’s secret blog, “I-Can’t-Stand-My-Wife-Dot-Blogspot-Dot-Com.” When a friend urges her to read the husband’s posts and share her feelings, she changes the subject.

Galchen is skilled at obscuring the tension of a story. With humor and linguistic sleight of hand, Galchen, like life, dazzles us into forgetting certain inevitabilities. Galchen’s finest writing occurs when her characters dangerously dip below their own surfaces and finally acknowledge something. In one striking passage, the unnamed narrator of “The Lost Order” elegizes her now-gone job: “I handled quite a large number of mold cases. I filled out the quiet fields of forms. I dispatched environmental testers. The job was more satisfying than it sounds, I can tell you. To have any variety of expertise, and to deploy it, can feel like a happy dream.”

Many of these stories feature a type of avoidance that often takes the pattern of a male character asking a direct question and a female narrator responding as if she hasn’t heard or doesn’t understand the question. In “Dean of the Arts,” our narrator flees to Mexico City to vaguely escape a vague problem: “I was going through an intense bout of fearfulness that is too irrational and stupid and elusive to explain,” then encounters an odd mystery (there are two men who may or may not be named Macheko. Are they, in fact, one and the same Macheko? Our protagonist investigates). The husband wants to address the danger at home, but his wife swats it away: Yes, but what about this Macheko mystery? This pattern of deflection can feel repetitive, as the “real danger” posed to characters is brought to the reader’s attention in the same way over and over: through scenes of two people speaking meaninglessly to one another.

This is not to say that the depiction of two people speaking meaninglessly to each other isn’t an artful device. Readers of Galchen’s widely appreciated debut novel, Atmospheric Disturbances, will be familiar with her unique ability to make (mis)communication at once funny and painful. What this device points to, if a bit too finely in this collection, are the other questions asked by the book. When loss occurs, why does it leave in its wake so much that is unknowable? How is it that people we love can become strangers to us, or disappear without explanation? Even the small details circle the theme of inexplicable absence. In “The Late Novels of Gene Hackman,” the narrator has, for a trip to Key West, packed a book about Ettore Majorana, the famous particle physicist who vanished in 1938. In the final story, “Once an Empire,” the narrator watches helplessly from the street as every object she owns escapes unaided out her apartment window, down her fire escape, and off into the night. The most interesting conversations occur metatextually. “The Lost Order” ends with line-by-line similarities to “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”; Gogol’s the “The Nose” and Borges’s “The Aleph” are reimagined in Galchen’s “American Innovations” and “The Region of Unlikeness.” Why the story-to-story ekphrasis? The most thematically fitting reason would be a tender attempt to keep a beloved story alive, to extend its life by entwining it with the DNA strands of a new story.

There are many mysteries and few discoveries in this collection. Each story reiterates what is, perhaps, the only plausible reality: In the end, we are alone with no answers. Still, Galchen’s characters do their best to deny this. One says to another: “Maybe I’m not in pain.” The other responds: “I’d put my money on pain. It’s the Kantian sublime, what you’re experiencing. There’s your life, and then you get a glimpse of the vastness of the unknown all around that little itty-bitty island of the known.” American Innovations ultimately points us toward the preferably ignored truth of the vast unknown, the fact that—as one narrator says while considering various paradoxes—“At the heart of it is the inescapability of our fate.”

Chloé Cooper Jones studies and teaches philosophy in New York City. She is the interviews editor at Gigantic.