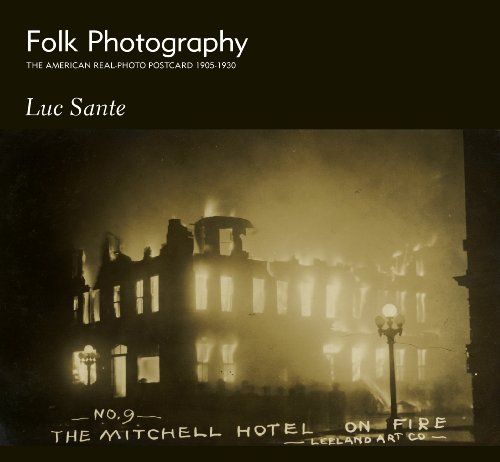

Anyone who haunts the bins of old photographs at flea markets and junk shops knows both the fascination and the dizzying tedium of wading through images from the vanished world. But Luc Sante, in his collection of some 2,500 "real-photo postcards," has cultivated a sweet spot in photographic history, when early-20th-century Americans enthusiastically gazed at their social vista, a gaze as intense as its small-town horizons were narrow. His Folk Photography: The American Real-Photo Postcard 1905-1930 presents 122 such cards, which were actual darkroom prints, often produced for sale by itinerant photographers or self-appointed documentarians.

These postcards were intended to bridge a gap in space, but they nearly as easily travel across time. Unlike ordinary family-album snapshots, which are private but unmysterious, they are personal gestures to all that is public. They invite the viewer to be an eyewitness to something extraordinary: the aftermath of a riot over streetcar fares, or a tug-of-war to celebrate a town's fifth anniversary. Even vacation photo postcards seem to offer evidence of carrying out a communal rite, without smiles or other tokens of interior feeling.

The cards' content might seem strange to us, but it also seemed strange enough at the time to be recorded. Much can be categorized as the physical, commercial, and spiritual epiphenomena of the throwing up of new settlements across the U.S. interior (and of those towns' first encounters with flood, fire, lightning, train wrecks). Still, the frames encompass details that gain particular piquancy from the passage of time. Some of these details are of historical interest, like a poster for "Anthracite" beer visible in a coal-country portrait of the Rough & Ready Cornet Band. Others harbor dramatic mysteries, like the baleful glare of a woman who may or not be the mother of the limp infant on her lap, who, you can’t help but think, may or may not be dead.

Sante, in a characteristically oracular introductory essay, emphasizes our distance in time from these photographic acts. But we can just as well marvel at the compression of history within the lifetimes of some people still walking the Earth today (maybe even that baby). John Shell, subject of a 1919 carnival post card calling him the Oldest Man in the World, probably wasn't really 131, but the card nevertheless claims a living link to the 18th century.

The postcards bristle with startlingly sharp dirt and wood and brick, recognizable as "reality" in the photographic language we share with the picture-makers. But while we grew up with that language, they were still inventing it, and therein lies the thrilling dissonance. Sante notes that real-photo postcards became obsolete when they were "insufficiently aspirational for people suddenly conscious of the great mass of images now saturating the world and nervously measuring themselves against it." That's us. More important than the glimpses of a lost time is the way that the postcards in Folk Photography—plainspoken, omnivorous, and experimental by necessity—refresh our exhausted ways of seeing.

Jonathan Taylor has written for publications including The Believer, Stop Smiling, the Village Voice, The Nation and Time Out New York.