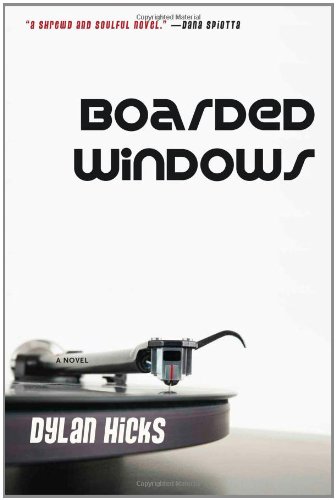

Boarded Windows must be appreciated as one of those debut novels that strike their own dizzy balance. It’s a rock’n’roll story couched in Proustian delicacy, a Beat reconfiguring of the family that moves towards pomo deconstruction of any reliable relationship—and withal, a hybrid of highly pleasing shape. Indeed, this fiction derives in part from another medium, that of the folk song. Doesn’t Bob Dylan (slyly alluded to here) insist that folk is about mystery, its details like glimpses between boarded windows? And isn’t this Dylan (Hicks, the novel’s author) also a singer-songwriter, with three well-received albums to his credit (and fourth will be released alongside this book)?

Accomplishment like that lies beyond the reach of the narrative’s major players, though all define themselves, pitiably, by dreams of better. The fulcrum of events, or what passes for event, is a utility player on the Midwestern rock circuit, and that’s the story’s milieu as well. Climatic revelations take place over rewarmed slices of pizza and detour into a recitation of North Dakota towns. So too, when the speaker starts to rhapsodize about the landscape, “the Plains sunflowers yellowing the roadside, the little bluestem empurpling the prairie,” his listener smells a ruse: “Can you stop?”

A ruse is always in the air around Wade Salem, part-time DJ and songsmith, full-time bullshitter. As the primary action gets underway, in the winter of 1991-92, Wade has reached middle age with rakish looks intact and splendid prospects—a DJ gig coming up over in Berlin. At the moment, though, he needs to crash in the Minneapolis apartment of a young couple almost as unmoored as he. The girl of the couple is Wanda, dabbling in experimental performance (and lovers of her own gender); the boy is our narrator, simmering with his own ambitions, among them a writer’s ambition. It’s this young Werther (to cite another allusion) who brought Wade to their door, with his LPs and his pot. For a little more than a year, not quite 15 years earlier, “I called Wade my stepfather.”

Our protagonist never knew his actual father. So too the woman who raised him, Marleen, was no more his mother than she was Wade’s wife - or than she achieved her own pathetic aspiration, that of a French scholar. The story of how Marleen adopted the baby narrator from a troubled college acquaintance proves one of the novel’s first triumphs: a tale recollected in the ’90s, first revealed in the ‘70s, about bright, doomed vagabonds of the late ’60s, the whole shebang cohering into heartbreak entirely of the moment.

Questions of parentage grow more insistent, prompted by the resemblance between the makeshift family of the early ’90s and that of the late ’70s. Still the boy of the family, in either case, remains unnamed. Every lurch towards some truth of origin, whether in dusky memory or wary confrontation, thrusts the main character deeper into unknowing. Does it mean nothing that he enjoys an “electric cuteness” like his smooth-talking guest’s? Wade’s flimflam past included a sojourn with the boy’s real mother, it turns out, in another anecdote that starts off beside the point and ends up spellbinding. All that’s solid melts away, and cracks appear, too, in the relationship with Wanda.

The boyfriend puts the blame on their boarder, but the true threat may be another woman, not unlike Wade in her blend of performance and con: “She had no artistic talent as conventionally understood, but she had the spirit of art… the art of living artistically as a nonartist.” Or should we say, living delusionally as a nobody? Adrift on the American Dream, no matter how often the figure onstage proves a “Bozo, a “charlatan”?

That betrayal, a hero’s, a father’s, takes quieter forms in the novel’s denouement. The closing image speaks of music in “free time,” a rejection of closure, and this may disappoint. Such a reading, however, ignores the luxurious open-throated quality that has been, throughout, the great pleasure of the text. The evasions of the dialog, ear-perfect, are paired with meditations that embrace vocabulary like “lazzaroni” and “ephebe.” The free hand with allusion tosses in everything from Jagger-Richards (“as black as the vision of the painted red door”) to Beckett’s Molloy to Gilbert Sorrentino’s Mulligan Stew. If our narrator is weaving a home, a magpie’s nest, he’s tucked in glinting strands of finery, and I was never less than entranced, really. Happily I succumbed to this voice, at once downtrodden and finicky, its apercus rising at times to devastating effect:

Back then I still held the American teenager to be the greatest invention of the twentieth century…, had a particularly patronizing and romantic view of black youth culture, and was a dogmatic opponent of the suburbs, where I now live, alone and unprosperously.

The Sea-God’s Herb, a selection of John Domini’s essays and reviews, will appear soon on Dzanc Books. See johndomini.com.