Just Like Heaven

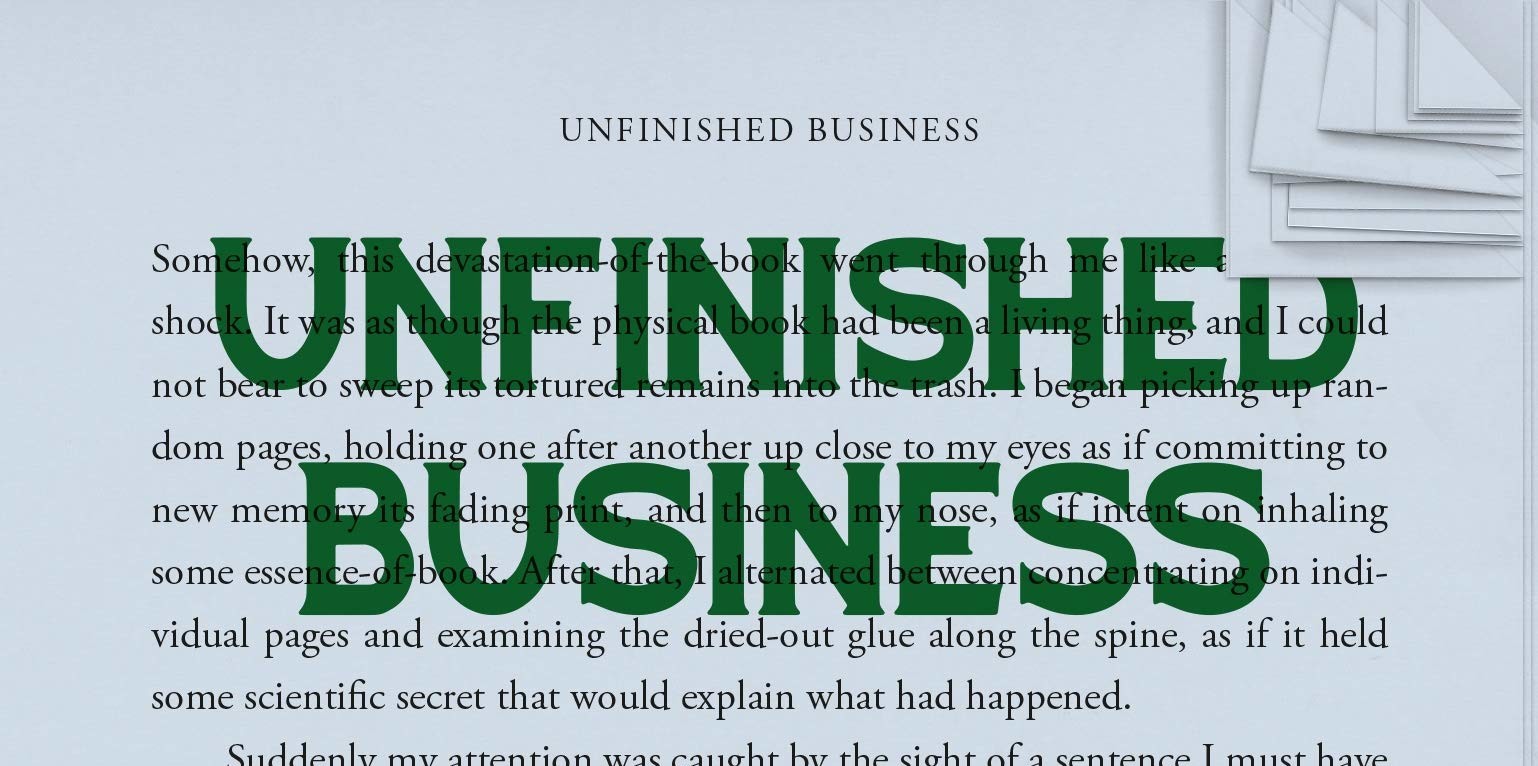

The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold