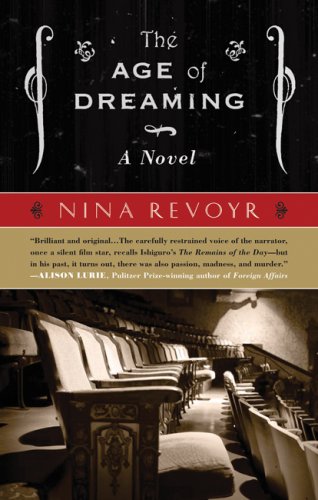

The star of Nina Revoyr’s third novel, The Age of Dreaming, is ostensibly Jun Nakayama, a silent-film-era Hollywood heartthrob. But the book’s real luminary is Los Angeles— old Hollywood in particular—a place where big dreams and big business rubbed shoulders, but with less treachery and friction than they do today.

The Age of Dreaming tracks the way LA and the movie world changed between the ’20s and the ’60s. Jun, who by 1964 is long retired and living in obscurity, receives a telephone call from a journalist and silent-film enthusiast, Nick Bellinger, who’d like to interview the aged actor. But Bellinger, Jun learns, has an ulterior motive: He’s written a screenplay and has already talked a slick Hollywood player into considering Jun for one of the parts. The offer leads Jun to revisit the past, reflecting on his arrival in the United States in 1907, his enormously successful film career, his romances and frustrating almost romances, and, finally, the event that would end his life as an actor: the unsolved murder of a famous director, a crime in which Jun was implicated.

Revoyr paints a rich, detailed picture of old Hollywood—not just the business but the way of life that sprang up around it. She describes the haunts where Jun and his fellow artists would gather for drinks and gossip, later flashing forward to show how one of those elegant watering holes has become a shelter for the homeless. Revoyr is particularly sharp about the racism that simmered in Hollywood (and throughout California) in the teens and ’20s—a review of one of Jun’s early films reads, “Nakayama is brilliant at conveying the beastliness of the Oriental nature”—and she expresses with subtlety the sense that those attitudes were simply business as usual for a successful Japanese professional working in a mostly white world. Revoyr is also smart about recognizing the ways in which early-twentieth-century immigrants had to live with racism. She understands that even though many of them accepted attitudes they couldn’t correct, they may nevertheless have longed for change.

Unfortunately, The Age of Dreaming lacks a strong dramatic backbone. Jun is reserved, well mannered, and perpetually elegant, and yet as he moves through a series of life-changing events, he always seems to be drifting; we know which moments in his life are most significant because Revoyr points them out, not because she makes us feel what it’s like to be in his skin. Still, this is a tender, heartfelt book, and Revoyr certainly appreciates the gentle power of early cinema. At one point, Jun reflects on his life’s work: “There was a purity to silent films that can never be recaptured in this clamorous age of sound effects and talking. We who made them knew that the most vital parts of stories—as of life—can never be reduced to mere words. We understood that moving images are the catalysts of dreams—more eloquent when undisturbed by voices.” Revoyr resurrects the old old Hollywood, from the time before talkies, and dreams it into existence once again.