Rae Armantrout is the most philosophical sort of poet, continually seeking in her collections to summon and surmise the contemporary character of subjective experience and, further, to test the limits of knowledge. Yet these meditations are often counterintuitive and sometimes downright absurd in their complexion, referencing cartoon characters (Wile E. Coyote and Rainbow Frog), miming the standardized phrases of tabloid headlines and business transactions (“These temporary credits / will no longer be reflected / in your next billing period”), and rehearsing bits of dialogue rooted only in the vapid grammars of cultural cliché (“I think our incentives / are sexy and edgy”).

With such seeming self-contradiction, Armantrout is a special case even to the extent that she willingly turns a critical eye on her own poems, aware of the possibility that they risk mirroring a kind of commodity logic, merely fulfilling conventional expectations for poetry as an expressive medium. As she once put it pithily, “[Readers] want to identify with the speaker of the poem as one might identify with an action figure,” and so they might seek in poetry only a “confirmation of what they already feel (or wish they felt).” This observation explains much, in fact, underscoring Armantrout’s bond with her generation’s appropriation artists, who were similarly suspicious of traditional conceptions of expressivity. Better to draw from the well of the mass media and disrupt its modes of transmission than to remain locked up in romantic, prepackaged notions.

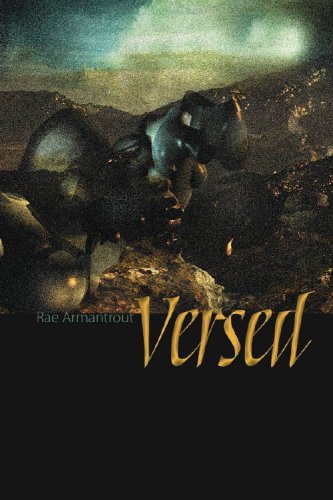

Armantrout’s writing in her latest volume, Versed, will thus be familiar to her longtime readers for its way of holding meaning (and identification) in uneasy suspension. Short lines in brief poems are polyvalent in both voicing and implication, inviting multiple readings. (In the context of what Armantrout has called her “faux-collage,” the bloodless billing statement quoted above easily assumes metaphysical import, for instance.) Her crystalline word selection underscores her motive for indexicality—“Any statement I issue, / if particular enough, // will prove / I was here,” she writes, as if words could be like hands with a firm grip on things—and yet her crisply pop vocabulary belongs also to the realm of high-definition television. Armantrout ably frames a highly mediated world using its own language, even as she deftly employs quotation marks and overly familiar diction to delineate those voices we “receive” in contemporary culture, leaving open and in perpetual play in her compositions the question of where the real begins and the (pre)fabricated ends, or where the poet emerges and where she disappears.

Indeed, the recurrence of already-known phrases and images seems to predicate an active desire—or Pavlovian impulse, as the case may be—among figures in the poems to locate themselves within that continuum. These are characters who want to be in character. A woman buying a gallon of vodka “may imagine herself as an actress playing an alcoholic / in a film,” Armantrout imagines. Elsewhere, an anonymous voice calls out, “Hey, / my avatar’s not working!,” while still another poem sounds a note of estrangement in the face of such media: “To be beautiful / and powerful enough / for someone / to want to break me / up // into syndicated ripples.” (Again, isolated, these lines are compelling enough, but their metaphoric value accrues only in context.) In this regard, Armantrout’s poetry might well have previously suggested that subjectivity today is in a dialectical embrace with the forces of media, looking for moments of cathexis or catharsis, but her very first poem here, the three-sectioned “Results,” implies that the ante has lately been upped, with media inviting participation from its consumers, so that their “expressed” voice is just the one given to them:

Click here to vote

on who’s ripe

for a makeover

or takeover

in this series pilot.

votes are registered

at the server

and sent back

as results.

As in Armantrout’s other work, it is in the space left open for the reader, who must navigate these voices, that the potential for alternatives resides. (The instability allows the reader to create his or her own meaning even while aware of any given poem’s constructedness. Of course, this meta-self-consciousness also gives rise to comic irony. Another fine line: “Symbolism as the party face of paranoia.”) But the second section of the book, “Dark Matter,” underscores a new sense of what’s at stake: Having recently dealt with cancer, Armantrout sets certain poems in the hospital and juxtaposes her witticisms with brutal lines about her sickness—with the science of cellular structures presenting in these poems a difficult extension of interpretative dilemmas in text. (Following the billing language above: “Metaphor / is ritual sacrifice. // It kills the look-alike.”) How do you, after all, mull matters of life and death when hearing the music pumping out at the local Starbucks? What space can you occupy then? A passage from the poem “Pleasure”:

Only distinctions can

matter.

(Canned matter.)

The irony cuts two ways, at once opening up and closing off possible experience, yet pleasure arises in contemplating both the options and the paradox.

Tim Griffin is the editor of Artforum.