We live in an era of food separatism. Among our factions are the locavores, the vegans, the raw foodists, and the sustainable agriculturists. We have grass-fed beef, grass-finished beef, organic produce, minimally treated produce, and people who swear by or disparage some or all of the four. We have theory after theory—scientific, political, personal—about what to eat and why. We have Top Chef and Iron Chef, and never the twain shall meet.

What we don’t have is a modern-day Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, who, in addition to being a lawyer, a politician, a professional violinist, and, by his own charmingly immodest estimation, “a doctor, chemist, physiologist, and even something of a scholar,” was perhaps the most passionate food generalist ever to roam the earth. Born in eastern France in 1755, his only claim to expertise was that he was the first person to realize, as he “considered every aspect of the pleasures of the table, that something better than a cook book should be written about them.” It’s thanks to him that we’ve all uttered what remains the ultimate statement on food—indeed, the very bon mot that may well have led to the aforementioned fracturing of our eating identities—“You are what you eat.”

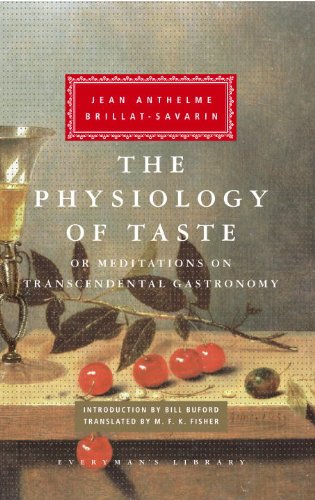

This aphorism first appeared, in a slightly longer form (“Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are”), in 1825, in the opening section of Brillat-Savarin’s final product—so much better, as he promised, than a mere cookbook—The Physiology of Taste: Or Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy. This masterpiece, published when he was seventy (he died two months later), has never been out of print and has just been reissued by Everyman’s Library ($25), which has paired M. F. K. Fisher’s intelligent, pitch-perfect 1949 translation from the French with a fine introduction by Bill Buford. It remains, close to two hundred years after its debut, a marvel, made up of more moving parts than one might think it possible to fit into a single book. There are dialogues, essays, and “Meditations” on everything from appetite and dreams to thinness, thirst, and the “Theory of Frying.” There is the delightfully named “Varieties” section, which includes a great deal of poetry and also a little treatise on the “Effects and Dangers of Strong Liquors.” There are, of course, some recipes (“I have tried among many other methods to make coffee in a high-pressure pot; but the result was a drink bursting with oils and bitterness, good at its best for scraping out the gullet of a Cossack”).

There is also a great deal of Brillat-Savarin’s autobiography, about which he is self-aware if unrepentant. “I could be accused, I know, of letting my pen run away with me occasionally,” he writes in his preface, “and of garrulity in my storytelling. But is it my fault that I am old? Is it my fault that, like Ulysses, I have known the manners and the towns of many nations? Can I be blamed for writing a little of my own life story?”

Honestly, no, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. His stories infuse The Physio-logy of Taste with a warmth and zaniness not easy to find in food books these days, reminding us that rather than a bully pulpit, eating is a function of our daily lives and thus sets the stage for every other action we perform. Brillat-Savarin knew this, I suspect, better than many people of his era, and without a doubt better than most of ours; his book is bursting with an array of tales that show precisely why dining is about so much more than just eating. In “Official Way of Making Chocolate,” he recounts what may be the only conversation on record about the epistemological aspect of hot cocoa:

“Monsieur,” Madame d’Arestel, Superior of the convent of the Visitation at Belley, once said to me more than fifty years ago, “whenever you want to have a really good cup of chocolate, make it the day before, in a porcelain coffeepot, and let it set. The night’s rest will concentrate it and give it a velvety quality which will make it better. Our good God cannot possibly take offense at this little refinement, since he himself is everything that is most perfect.”

And you thought cleanliness was closest to godliness!

Or take, on the other end of the spectrum, this “Anecdote,” which appears in “Meditation 11: On Gourmandism”:

One day I found myself seated at the dinner table next to the lovely Mme. M . . . d, and I was silently congratulating myself on such a delightful accident when she turned suddenly to me and said, “To your health!” At once I began a compliment to her in my prettiest phrases; but I never finished it, for the little flirt had already turned to the man on her left, with another toast. They clicked glasses, and this abrupt desertion seemed to me a real betrayal, and one that made a scar in my heart which many years have not healed over.

There is drama before the meal has even begun, which, one presumes, is precisely the way Brillat-Savarin likes it (who doesn’t?), and even this emasculation fails to daunt his enthusiasm for his subject. Its retelling is followed almost immediately by a section titled “Influence of Gourmandism on Wedded Happiness,” one of many instances in which the author wanders off in the direction of sex when he’s supposed to be talking about food, so that before you know it, a meditation on le gourmand has become one on l’amour.

Which, of course, is part of what makes Brillat-Savarin’s writing so alluring: He’s a sensualist, which ought to be a requirement for anyone writing about food (or, to put it another way, a chef friend of mine once told me he didn’t trust thin chefs because he saw it as a sign they weren’t interested enough in the food to be constantly tasting it). He’s also someone you’d like to have dinner with yourself, if only you wouldn’t have to sit through the French Revolution to do it (and maybe even if you did). Who wouldn’t want to chat—OK, flirt—with a man who can write a book with a section called “About Fondue” and another called “The End of the World” and still somehow find a place to squeeze in his thoughts on what was apparently the burning question on everyone’s mind in nineteenth-century France: “Are Truffles Indigestible?” Even Fisher was unable to resist him, writing in a translator’s note for the 1971 edition of her text: “I see no need to add to what I wrote then, except perhaps to avow that my love for the old lawyer burns as brightly now as ever.”

“Men who will come after us will know much more than we of this subject,” Brillat-Savarin admits readily. He’s referring specifically to the science of taste—to chemistry, really. And though he was right about one kind of chemistry, about another he clearly understood a great deal. “Every modification which complete sociability has introduced among us can be found assembled around the same table,” he writes. “Love, friendship, business, speculation, power, importunity, patronage, ambition, intrigue.” We accept such pronouncements because their author is amiable, smart, and deadly in earnest about his subject without ever being preachy; his book is carried as much, if not more, by the force of his personality as it is by its contents. There was no occasion for its existence and no trend that encouraged it. It is ambitious but never calculating, written purely for its own sake and for the eyes of anyone who was able and had the inclination to read it.

This democratic impulse is perhaps worth keeping in mind as we head into the holiday season and face the seemingly innumerable mini-factions, foodie and otherwise, within our own families. Is there anyone who hasn’t been to a Thanksgiving dinner where someone’s eighteen-year-old cousin, returned home from college for the first time, suddenly announces a fanatic devotion to vegetarianism just as the turkey is being delivered to the table?

At such trying moments, you may long to get started on Brillat-Savarin’s recommended drinking scheme—“The proper progression of wines or spirits is from the mildest to the headiest and most aromatic”—in order to dull the chaos as quickly as possible. Instead, take a deep breath and repeat a different one of his aphorisms to yourself as the steaming bird is carved up and the gravy and rolls are passed around the table: “The pleasures of the table are for every man, of every land, and no matter of what place in history or society; they can be a part of all his other pleasures, and they last the longest, to console him when he has outlived the rest.”