“I was under the tragic spell of the South, which either you’ve felt or you haven’t,” John Jeremiah Sullivan writes in “Mr. Lytle: An Essay,” from his new collection, Pulphead. “In my case,” he continues, “it was acute because, having grown up in Indiana with a Yankee father, a child exile from Kentucky roots of which I was overly proud, I’d long been aware of a faint nowhereness to my life.”

Sullivan’s previous book, Blood Horses, was an extended meditation on the horse, adapted from a gripping cover story he wrote for Harper’s Magazine in 2002, “Horseman, Pass By.” I remember thinking it was one of the best magazine stories I had read in ages—a perfect blend of reportage, personal essay, cultural criticism, and amateur-historian musings.

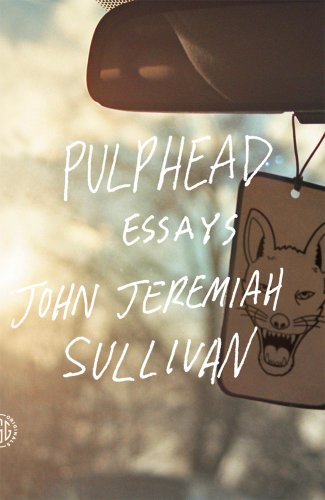

Pulphead follows in this same tradition, collecting much of Sullivan’s magazine writing over the past decade. The book’s pieces appeared originally in GQ, Harper’s (where Sullivan currently serves as a contributing editor), the Paris Review (where he is “southern editor”), and the Oxford American (where he was an assistant editor in the late ’90s). Sullivan has retooled them a bit here, so that they can speak more directly to the writerly preoccupations that lay behind them, and fit alongside each other in a more cohesive whole.

Sullivan’s prose is unpretentious and self-assured. He channels an innate sense of storytelling, coupled with a love for, and knowledge of, southern literature; the end result calls to mind some of the best New Journalism of the ’60s and ’70s. Sullivan’s essays stay with you, like good short stories—and like accomplished short fiction, they often will, over time, reveal a fuller meaning.

But what makes this collection so refreshing is that the reworked essays radiate an even brighter light than when they first appeared in print: Sullivan’s experiential stories epitomize the write-what-you-know ethos, so conspicuously absent from most product- and PR-driven commercial magazines today. (Fittingly enough, the collection draws its title from a rescinded letter of resignation Norman Mailer wrote to Esquire during his brief but colorful career as a magazine editor in 1960: Good-bye now, rum friends, and best wishes. You got a good mag (like the pulp-heads say) . . .)

In “Upon This Rock,” for example, Sullivan delivers an expansive yet gripping confessional account of his complicated relationship with Christian rock. Renting an RV to attend the Creation Festival in rural Pennsylvania, Sullivan drives over from the East Coast with some young Christian-rock “hard-core buffs” in their late teens. This is immersion journalism at its best:

In fifteen minutes, all my ideas about Christians were put to flight. . . . I started asking questions, lots of questions. And they loved that, because they had answers. Your average agnostic doesn’t go through life just primed to offer a clear, considered defense of, say, intratextual Scriptural inconsistency. But born-agains train for that chance encounter with the inquisitive stranger.

Meanwhile, Sullivan’s meditations on rock icons Michael Jackson and Axl Rose (both Indiana natives) underscore his ability to glean fresh details about even overexposed celebrities. Of Rose, he notes that “the readers of Teen magazine, less than one year ago, put him at number two (behind ‘Grandparents’) on the list of the ‘100 Coolest Old People.’” In the 2006 profile, Sullivan captures the former Guns N’ Roses front man at a point when he “hasn’t released a legitimate recording in thirteen years,” a period during which he had “turned into an almost Howard Hughes–like character—only ordering in, transmitting sporadic promises that a new album, titled Chinese Democracy, was about to drop, making occasional startling appearances at sporting events and fashion shows, stuff like that—looking a little feral, a little lost, looking not unlike a man who’s been given his first day’s unsupervised leave from a state facility.” Toward the end of the book, Sullivan likewise delivers memorable profiles of Bunny Wailer (the last surviving founding member of legendary reggae band the Wailers) and folk guitarist/blues enthusiast John Fahey in the twilight of their careers, never allowing their cult-hero legends to get in the way of a better story.

His portrait of the eccentric nineteenth-century naturalist Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, on the other hand, has an unusual scholarly quality to it:

He showed up still wanting to know it all, to be a synthesizer. He didn’t see it was a time instead for clean, precise, empiricist gathering. His books, he quaintly announces, are henceforth to be thought of as volumes in a life’s work, the Annales de la Nature. Deep down he’s still in Grandmother’s library. And then he goes to America, where the profusion of unclassified organisms that has helped to trigger these methodological and conceptual upheavals to begin with lies waiting.

Whether he ponders the legacy of a long-dead French scientist or the unlikely cultural trajectory of Christian rock, Sullivan imbues his narrative subjects with a broader urgency reminiscent of other great practitioners of the essay-profile, such as New Yorker writers Joseph Mitchell and A. J. Liebling or Gay Talese during his ’60s Esquire heyday. And like such forerunners, Sullivan has a suitably restrained sense of his own place in the story; in lieu of a traditional author’s introduction, Pulphead opens with a police mug shot of Sullivan as a teenager, followed by the Mailer resignation note as its epigraph. This point of entry speaks volumes about the subtle yet assured writer Sullivan is today—while the material that follows reinforces his standing as among the best of his generation’s essayists.

J. C. Gabel is the founding editor and publisher of Stop Smiling magazine and edits and publishes Stop Smiling Books.