Joe Brainard achieved a singular position in the poetry world before his death from AIDS-induced pneumonia in 1994. An artist identified with a rarefied strain of Pop art, he was also a poet affiliated with the so-called New York School, a loose collection of wry Francophiles who could be readily described in the mid-’60s as avant-garde without anyone wincing at the designation. Ensconced in the circumscribed world of highbrow, camp-inflected culture, Brainard penned I Remember—a litany of self-regard whose formal rigor sharpens the kind of intimacies that invite readers to feel like coconspirators. The multibook work escaped New York’s narrow precincts to reach a wide (for modern verse) and enthusiastic readership. Along with Ginsberg’s more famous “Howl,” I Remember is the post-1950 poem people who don’t read poetry might know. That major effort, along with other poems, prose pieces, and drawings done over Brainard’s three-decade career, have been gathered in one volume by the Library of America. Smartly edited by his lifelong friend Ron Padgett, the collection demonstrates that this unlikely success was no fluke.

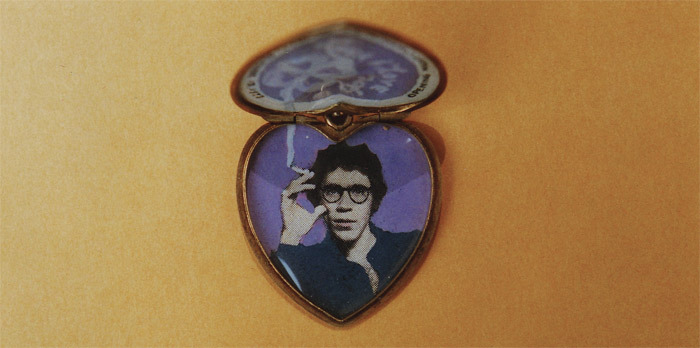

Brainard arrived in New York in 1960, along with fellow Tulsa teens Padgett and Dick Gallup; another Oklahoma pal, Ted Berrigan, soon joined them. He began writing poems, making art, and meeting the people—Frank O’Hara, Andy Warhol—who would prove influential in both endeavors. Having settled on the Lower East Side, Brainard began producing collages, drawings, and paintings, appropriating images and texts from popular culture and the city’s street life. In a 1977 interview with poet Tim Dlugos (included in this volume), he recounts being inspired to make altarpieces by the “Puerto Rican religious . . . junk” he found on display. This would prove to be a signature gesture—assimilate, repurpose, and subvert—that would eventually play out, for instance, in an extensive series of collages devoted to the comic-strip character Nancy, in which the spiky-haired imp can be found hiding in the “basket” of a sailor’s pants or spouting non sequiturs while caught in flagrante delicto. Brainard liked to help the pure products of America go even crazier.

If O’Hara was, in the words of critic Marjorie Perloff, a poet among painters, Brainard worked with equal vigor on both teams. His visual and verbal art cross-pollinated, and this was never more evident than in I Remember. Initially published in several editions (I Remember, I Remember More, More I Remember More) by the small press Angel Hair, this serial work has been collected to form an epic incantation. Like some liturgical rite that emphasizes its own trance-inducing music, the 130-page poem rings out with a series of simple declarative statements, each beginning “I remember.” But the length and repetition hardly ever cause our reading to drag. I Remember speeds along, a broken-field, decidedly unchronological dash through the poet’s life that manages to feel both condensed and expansive at the same time: “I remember chalk,” an observation elemental and universal, is closely followed by the more discursive and personal “I remember how much I tried to like Van Gogh. And how much, finally, I did like him. And how much, now, I can’t stand him.”

Drawing on his dadaist and surrealist experiments in art and infusing their juxtapositional impulses with his own calculated offhandedness, Brainard gave birth to a wholly original (and, despite its numerous homages and exemplary employ in a thousand creative-writing classes, near-inimitable) form: the collage memoir.

To note I Remember’s utter freshness when it began appearing in the early ’70s isn’t to discount its antecedents: There’s Whitman’s dithyrambic listing (in his introduction, Paul Auster enumerates Brainard’s myriad topics—more than a hundred entries for “The Body,” fifty for “Holidays,” and “Movies, Movie Stars, T.V., and Pop Music” scoring several dozen); Proust’s obsessional verve for detail (“I remember the very thin pages and red edges of hymn books”); and Christopher Smart’s call-and-response patterning in Jubilate Agno, in which every line starts with either “Let” or “For.” Brainard joined these formal approaches to his quicksilver and utterly congenial sensibility; the poetic thrill in I Remember derives not from inventive imagery or linguistic sport, but rather from the piquant, piercing evocation of Brainard’s charm. He routinely renovates sentimentality with the slightly perverse and still ends up landing sweetly: “I remember playing doctor with Joyce Vantries. I remember her soft white belly. Her large navel. And her little slit between her legs. I remember rubbing my ear against it.” Or he elevates confessional intimacy to self-dramatizing: “I remember, eating out alone in restaurants, trying to look like I have a lot on my mind. (Primarily a matter of subtle mouth and eyebrow contortions.)” Cultural history is digested and crystallized: “I remember movies in school about kids that drink and take drugs and then they have a car wreck and one girl gets killed.” Even though Brainard performs Brainard with great élan, the show never feels ego-driven; his poems could be transcriptions from a late-night talk with a close friend who wanders through matters both striking and banal with equal aplomb, refusing to recognize the difference, but not for a moment failing to entertain you.

If there is a unifying theme that emerges from the poem, it might be the fluidity of the self—the posited truth that our memories, beliefs, and feelings are always in flux and thus ever redefining who and what we are. In the Dlugos interview, Brainard talked about the composition of I Remember: “I have a terrible memory. . . . But then I began to realize that beyond that point there is another level of knowledge that could be triggered off.” The deliberateness of the enterprise, this “triggering,” may seem an odd source for a poem that flows with the insouciance of conversation, but this is the crux of Brainard’s art—the meticulous construction of naturalness:

I remember the first erection I distinctly remember having. It was by the side of a public swimming pool. I was sunning on my back on a towel. I didn’t know what to do, except turn over, so I turned over. But it wouldn’t go away. I got a terrible sunburn. So bad that I had to go see a doctor. I remember how much wearing a shirt hurt.

This casual recollection (which slyly embeds a parable of sexual guilt and punishment—is this the other “level of knowledge”?) registers ingenuously. The speaker is familiar, and the anecdote is, too. The next entries shift sharply:

I remember the organ music from As the World Turns.

I remember white buck shoes with thick pink rubber soles.

Here the lens tightens focus—even as it verges on camp. The details—the cheesy theme from a daytime soap opera and the pavement-eye view of footwear—sit in pointed juxtaposition to the “authentic” memory of adolescent distress. Skillfully mixing tones and points of view, Brainard mimics the randomness of perception, as well as the unpredictability of emotional associations. The reader continues to zig with his zags, as these lines are followed by “I remember living rooms all one color.” We move in a blink from sexual secrets to pop-culture ephemera to sociological précis—the material is always kept in contrapuntal balance. Many entries begin, “I remember thinking . . .” or “I remember a story . . .” or “a daydream.” Memories of memories send us spiraling down the rabbit hole: It’s not just that we are always remembering, Brainard is saying, but that we are always remembering that we remembered.

Weighty as that idea is, it treads lightly through the poem. Brainard’s comedic touch—a deadpan wit that veers toward sincerity rather than sarcasm—marks all of his writing. Reliant on nuances of tone and inflection, it is the kind of graceful, openhearted humor that barely claims its laughter upon reading, yet you recall and recount to others weeks later. In full, the prose poem titled “Ron Padgett”:

Ron Padgett is a poet. He has always been a poet and he always will be a poet. I don’t know how a poet becomes a poet. And I don’t think anyone else does either. It is something deep and mysterious inside of a person that cannot be explained. It is something that no one understands. It is something that no one will ever understand. I asked Ron Padgett once how it came about that he was a poet, and he said, “I don’t know. It is something deep and mysterious inside of me that cannot be explained.”

Traditional tools are at work—alliteration, repetition, formalized diction—while the parodic intent is deftly turned. The coterie-style joke is on aesthetic theorizing and essentialist creeds (O’Hara’s “Why I Am Not a Painter” is close kin here), but it’s precisely this earnest intellectualism that sparks Brainard’s deeper jest. This is a poet who candidly reports to Dlugos that the poetry of longtime friend John Ashbery is, “you know, over my head. . . . My mind wanders off.” His sophistication was his simplicity.

The Collected Writings makes its case—Brainard surely belongs in this canonical series, in no small part because he represents that peculiarly American aspiration to self-mythologize in the face of an otherwise relentlessly quotidian world. But this is done gently, with affection and a profound sense of commonality with his readers. Sounding playful, sometimes naive notes, Brainard nevertheless advances a serious cause—the enlargement of the self to include all friends, family, movie stars, old high school teachers, anonymous subway riders, great artists, decisive moments, embarrassing scenes, hidden truths, celebrated falsehoods, and Dinah Shore. The welcome sign hung over this concoction of reference and remembering reads “Joe.” Brainard’s artistry can appear as plain as that name, yet all the while giving subtle, human-pitched voice to the many selves swirling beneath.

Albert Mobilio’s most recent book of poems is Touch Wood (Brooklyn Rail/Black Square Editions, 2011).