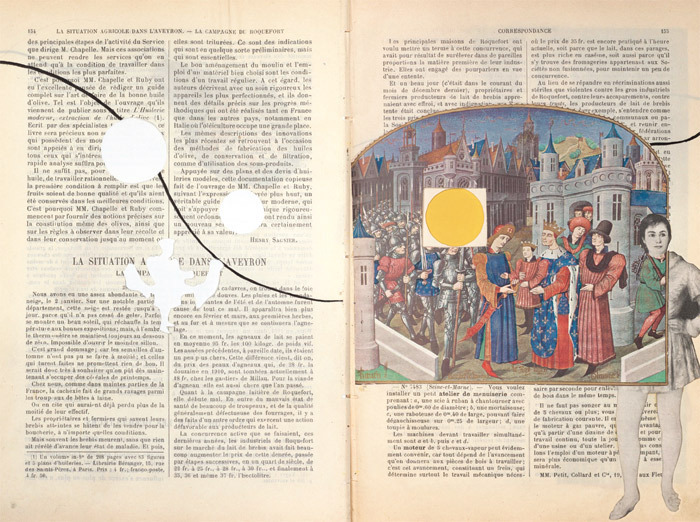

IN A SKETCHBOOK NOTE, Jasper Johns put the plan and practice of modern art simply: “Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it.” As an early-twentieth-century harbinger of this creative tack, Joseph Cornell’s Untitled Book Object was first displayed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in a 1998 show that also featured, appropriately enough, Marcel Duchamp. Cornell most likely acquired the French agricultural yearbook that became the basis for this work on one of his treasure hunts among the bookstalls and junk shops of Manhattan sometime in the early ’30s. Like so much of the bric-a-brac and ephemera (obscure postcards, pharmaceutical bottles, and astronomical instruments) the Queens native repurposed in his assemblages, this battered volume, the Journal d’Agriculture Pratique, was utterly ordinary and fit for disposal. The tome’s 844 pages—replete with tables, illustrations, and photographs—provide detailed information about weather, crops, and livestock, and this mere utility may be just what inspired Cornell. About a quarter of the pages have been altered—collaged with figures plucked as readily from Vogue as the Prado, cut out to create three-dimensional effects, and marked with the artist’s handwritten annotations. References nest within each other; any one alteration opens up a rabbit hole of art-world intertextuality. A tipped-in full-page reproduction of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa nods to Duchamp’s famously subversive L.H.O.O.Q. But Cornell places a couple of bottles of French perfume in her arms to deepen the homage, calling to mind Duchamp’s self-portrait of himself as Rrose Sélavy (itself collaged on a perfume bottle). Another tipped-in page, from the Chroniques de Normandie, shows French king Louis IV (above) handing the dauphin over to a general for training. Upending the scene (along with the cutout yellow circle—some kind of sunlike portal to another century?) is a figure sneaking off with keys, whose head has been replaced by that of nineteenth-century actress Henriette Henriot; her portrait has been snipped from a reproduction of a painting by Renoir. Again and again, the original columns of text and numerical tables about crop yields and rainfall constitute an aptly solemn stage for visual wit and a trickster sensibility. While only sixty pages have been printed for this facsimile edition (the rest are included on an interactive CD), they amply demonstrate the entrancing, evocative poetics of this redemptive art: Cornell took a discarded book, did something to it, and made it so new that over a century later we can peruse with delight the marvels to be found amid French farm facts.