Last year’s museum-quality Ad Reinhardt show at the David Zwirner gallery, complete with an atrium devoted to Reinhardt’s career-capping black canvases, prompted the thought that this cantankerous art-world maverick might be the quintessential mid-twentieth-century American painter.

A lifelong abstractionist and card-carrying member of the New York School, complete with a youthful WPA stint, Reinhardt made systemic, antiexpressive paintings that engaged those of the heroic action guys and wrote manifestos attacking the art world to propose a Jacobin notion of art-as-art. He anticipated the Minimalists and Conceptualists, and had points of contact with John Cage, Black Mountain College, and Fluxus. His late work got lumped in with Op art and was appropriated, in a way, by Pop—or at least by pop culture. A vitrine at Zwirner showed the degree to which his series of canvases known as the “black paintings” served as a butt for editorial gags and New Yorker cartoons.

The irony is that Reinhardt was himself a cartoonist of distinction, something that—along with his qualities as a teacher, gadfly, and satirist—is amply demonstrated in How to Look, an anthology of the comics Reinhardt produced for the advertising-free left-wing tabloid newspaper PM throughout 1946, as well as for Artnews and other art journals in the 1950s. Reinhardt’s PM comics bring to mind the exuberant ridicule with which New York newspaper cartoonists greeted the modern art that confounded the city in the 1913 Armory Show, except that Reinhardt was arguing from the other side of the aesthetic divide. Though not without an edge, his explication of modern art is largely a matter of civic-minded advocacy. It’s a New Deal in aesthetics—for which he received a fan letter from Sinclair Lewis. (Reinhardt, perhaps ironically, reprinted the letter next to his version of a 1937 Kandinsky non-objective painting, in the comic titled Hey, Look at the Facts.)

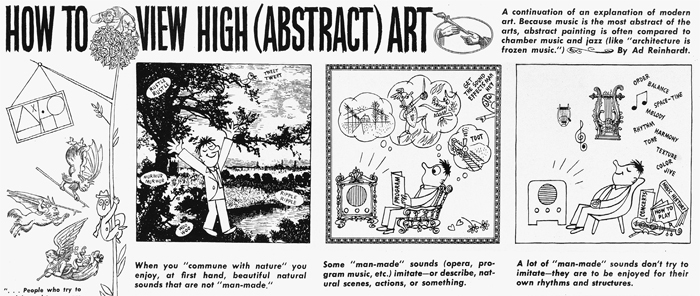

Reinhardt’s stint at PM began with a page titled How to Look at a Cubist Painting and, following up with How to View High (Abstract) Art and How to Look at Low (Surrealist) Art, continued for another twenty installments that, among other things, instructed his readers how to look at “space,” “art-talk,” “things through a wine glass,” and “looking” itself. The tone was friendly but feisty. How to Look at a Cubist Painting ends with a split-panel riff in which an inanely grinning cartoon figure points to an abstract painting—“Ha ha what does this represent?”—only to have the suddenly anthropomorphized canvas point to him and knock him sideways with the question “What do you represent?” (Reinhardt repeated this gag so regularly that it came to seem his mantra, or the visual equivalent of Mad magazine’s village-idiot mascot, Alfred E. Neuman.)

The “How to Look” series—with its elastic format and graphic busyness (the margin is a trove of jokes, messages, and quotations)—has a remote affinity to the rowdy all-over newspaper comics of the 1890s and early 1900s, and later info strips like Ripley’s Believe It or Not! or Rube Goldberg’s intricate single-panel gags, but it’s basically sui generis. Reinhardt was not only constructing essays, by posing questions, making visual comparisons, and creating parallel arguments, but also charting new territory: His PM pages don’t look like any previous comics. Much as he disliked Surrealism, the artist brought Max Ernst’s collage techniques to the tabloid press (perhaps his journalist antecedents are the fake photographs pioneered by the New York Graphic). Reinhardt, however, was far more eclectic and playful than Ernst.

Reinhardt’s comics make extensive use of what curator Robert Storr calls, in his catalogue essay, “a hoarder’s wealth of materials from old newspaper advertising, encyclopedias, and school textbooks.” Even the jazzy, casual-looking drawn material is collage-like, variously appropriating Egyptian hieroglyphs, medieval tapestries, recent clippings from the New York Times, and characters from the cartoons of Reinhardt’s PM colleague Crockett Johnson. The extravagantly taxonomic How to Look at More than Meets the Eye includes a collection of eyeballs by Klee, Miró, and Picasso. How to Look at Art & Industry mocks a Pepsi-Cola–sponsored painting competition with a cornball early-twentieth-century engraving of Socrates drinking the hemlock—Socrates tagged “American Artist” and clutching a drawn bottle marked, in reference to the current price war between Coke and Pepsi, “Nickel Drink Competition.”

How to Look at Modern Art in America is the most famous of Reinhardt’s PM pieces—an art-historical family tree in which abstract paintings diverge from illustrative pictures, with the latter branch about to crack under the deadweight of “Subject Matter” and a host of other dangling distractions (“Mexican Art Influence,” “Business as Art Patron”). Leaves labeled with the names of Reinhardt’s fellow abstractionists Hans Hofmann, Jackson Pollock, and Arshile Gorky are closest to the sun (with Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Adolph Gottlieb a bit below). Reinhardt himself is absent, although he does provide extra blank leaves for the reader to fill in as he or she sees fit.

Always polemical, Reinhardt’s cartoons associate abstract painting with left-liberal politics and figurative art with its opposite. In How to Look at Looking, the artist updates an old almanac drawing contrasting the brood hen of “Ignorance” with that of “Intelligence”; below them, a pair of stuffy-looking hens labeled “Progressive” and “Abstract Painter”—incubating the eggs of “Truth,” “Democracy,” and “Creativity”—oppose a scowling pair of birds, “Reactionary” and “Picture Artist,” which guard the eggs of “‘Free’ Enterprise,” “Ragged Individualism,” and “Hack-Skills.”

Hatred of the art market was a given, but post-PM, Reinhardt’s view of the art world itself grew increasingly totalized and caustic. Museum Landscape, drawn for the little magazine trans/formation in 1950, is filled with invented tendencies of bogus abstraction: the “Grand ‘Sweatshop’ Style”; the “Coney Island Trashbasket School” (exemplified by Ben Shahn); “Therapy Style, Turps & Vinegar ‘Abstraction’” (Pollock, Hofmann). Reinhardt’s friend and frequent target Robert Motherwell is a sprig on a solitary cactus labeled “Lonely Hearts School.”

In How to Look at Modern Art’s final iteration, published in Artnews in 1961, the healthy branch of the tree has simply vanished. The void is occupied by a pair of birds labeled “Curators and Dealers.” The void within the void, and perhaps the structuring absence, in this version of the comic is the textureless black square (“five feet by five feet by five thousand dollars”) that preoccupied Reinhardt from 1960 until his untimely death in 1967 and was characterized by the artist as “the last painting which anyone can make.” (Almost all of the paintings Reinhardt made in the final years of his life were versions of this black square.)

Storr’s essay puts Reinhardt’s comics in the context of Hogarth and Daumier, as well as the New York art world, but, in keeping with Reinhardt’s all-over-ness, there would seem to be other ways to historicize the art comics. One would be in the disappearing, if not defunct, realm of newspaper culture and the lost world of the Popular Front. PM staffers included I. F. Stone, Elizabeth Hawes, Dr. Benjamin Spock, Margaret Bourke-White, and Weegee; the tabloid’s editorial cartoonist was Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss.

In his PM comics, Reinhardt refers to himself as an “artist-reporter” and does occasionally comment on current shows—as well as, in How to Look at Iconography, “lines seen about town lately.” How to Look at a Mural is devoted entirely to Picasso’s Guernica, which had recently been installed in the Museum of Modern Art after a prolonged tour, while How to Look at 3 Current Shows singles out self-taught people’s artist Ralph Fasanella for praise: “Implicit everywhere here was the (good) democratic idea that creative-painting-activity belongs to everyone potentially and not to the few, special, hack-skilled, ‘sound craftsmen’ who produce dept-store pictures.”

Reinhardt’s early comics in particular are the precursors of the faux-didactic, attitude-drenched one-pagers that appeared in the first few years of the Harvey Kurtzman–edited comic book Mad and his subsequent magazines Humbug and Help! (Framing the art world in terms of tip sheets and bookies, Reinhardt’s 1951 Museum Racing Form is prototypical Mad.) Given that a left-leaning art-school dropout like Kurtzman might well have been reading PM in 1946, it’s not impossible that Reinhardt impressed him or that Reinhardt’s example may have led Kurtzman to encourage the “chicken fat” clutter that was the stylistic signature of his closest associate, Will Elder; what’s certain is that underground cartoonists R. Crumb and Art Spiegelman were deeply influenced by Kurtzman and produced even more self-aware, didactic comic strips.

A fondness for diagrammatic pages and the frequent shifts in styles and registers that Storr calls “pictorial disjunction” brings Reinhardt even closer to Spiegelman. The programmatically disjunctive frame from How to Look at a Cubist Painting (selected for How to Look’s cover) is practically a Spiegelman avant la lettre, while High Art Lowdown, Spiegelman’s hilarious review of the Museum of Modern Art’s “High and Low” show, a one-page strip published in the December 1990 issue of Artforum, is, both in form and attitude, a Reinhardt-style art comic drawn more than two decades after Reinhardt’s death.

Spiegelman’s point, satirizing the myopic class bias that divides high art from low, is not, however, Reinhardt’s. Reinhardt wanted to take art to its self-obliterating limit. His last cartoon was a mandala. His maximalist, garrulous, pedagogical art comics (as well as his epic slide shows and copious writings) are the captions tossed off en route to, as he puts it in one manifesto, “not confusing painting with everything that is not painting.”

J. Hoberman’s most recent book is Film After Film: Or, What Became of 21st Century Cinema? (Verso, 2012).