IN A 2002 press briefing about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, Donald Rumsfeld issued his now-infamous series of statements about “known knowns,” “known unknowns,” and “unknown unknowns.” Covert Operations: Investigating the Known Unknowns, which documents an exhibition held at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (Scottsdale, Arizona), takes its subtitle from Rumsfeld’s intentionally mystifying phrases. What methods of artistic response might speak to such a dizzying—and ultimately deathly—epistemological formulation?

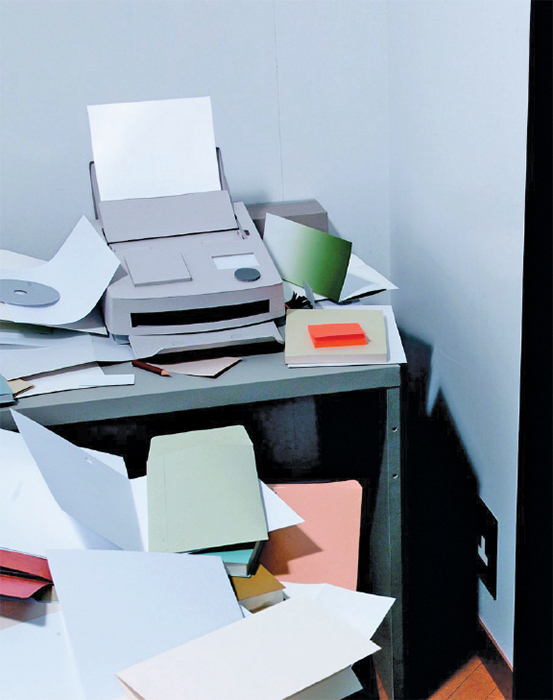

Cased inside a nifty-looking brown envelope with a string clasp that recalls older, analog forms of espionage, the book focuses on artistic practices in the wake of 9/11 that thematize questions of transparency, deception, privacy, and control. Bringing together works by Harun Farocki, Jenny Holzer, Trevor Paglen, Taryn Simon, and others, Covert Operations makes the claim that art—as a process of exposing concealed truths—can provide alternative narratives and shed light on our current condition. Much of this art uses digital technology, but a surprising number of works traffic in the material world, too, from Thomas Demand’s series of photographs of the paper-and-cardboard model he made of an office in the Niger Embassy in Rome (Detail XI, 2007) to Paglen’s collection of personnel patches from secret US-military operations.

Redaction is a major conceptual rubric as well as an overarching design element; the black lines obscuring text on the cover of the book echo Holzer’s PHOENIX yellow white (2006) paintings of FBI documents released under the Freedom of Information Act that are dense with struck-out words. Revealing hidden evidence by means of the FOIA, interviews, data gathering, and archives is a key strategy of many of the artists, and much of their work is documentary in nature (e.g., in David Taylor’s photographs of remote-surveillance technology along the US-Mexico border). At the same time, the pieces are insistently critical—not just dry compendiums of facts—as the artists bring their affective choices and aesthetic interpretations to these urgent projects. Such reframings raise larger questions about the persistently slippery relationship between veracity and fabrication, reality and simulation.

A few artworks take the form of direct resistance against the grinding mechanisms of power, as in Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0’s real-world devices to assist immigrants. But the book concludes on a pessimistic note: a still from the two-channel video projection 30 Days of Running in the Place, by Ahmed Basiony, an Egyptian artist who was killed in 2011 in Tahrir Square while filming the military police firing at protestors. What we know is this: Sometimes the cost of bearing witness is certain to be terrible.