Spoiler alert: I made the Big Fucking Steak. Of course I did. Because of all the recipes in Anthony Bourdain’s new cookbook, Appetites (Ecco, $38), it has the most Bourdainian recipe title, stamped in huge letters at the top of the page and preceded by a photo spread of an enormous dog in profile, jaws wide open and teeth glistening, about to pounce on a piece of raw meat. “Big Fucking Steak” is more like a mini-lecture than a recipe. It doesn’t tell you what cut of meat to buy (“look for marbling”). It doesn’t tell you what cooking method to use (Bourdain is agnostic when it comes to grilling versus pan-searing, the latter finished with butter in a very hot oven). It, like Bourdain in general, doesn’t deign to care about a lot of things that most cookbook authors care about. It does, however, make two demands. One of them is that “whatever you do, however you get there—when it’s done—or just shy of being done, rest your steak before poking, slicing, or otherwise interfering with it!” If this directive sounds awfully mundane for our resident foulmouthed, globe-trotting food personality, rest assured: Bad-boy Bourdain is here in full force, too. The only other thing he insists on when it comes to steak is that “American wagyu and Kobe are also two terms you want to be cautious about, as they are often little more than marketing bullshit and douche bait.” Hello, Tony!

Appetites is Bourdain’s paean to domesticity, to which he is a grateful latecomer, and which perhaps accounts for his lapses into a more modulated tone than we’ve come to expect. Now sixty, he’s become reflective while remaining obnoxiously unruly. “From age seventeen on, normal people had been my customers. They were abstractions, literally shadowy silhouettes in the dining rooms of wherever it was I was working at the time,” he writes in the introduction. “I looked at them through the perspective of the lifelong professional cook and chef—which is to say, as someone who did not have a family life. . . To the extent that I knew or understood normal people’s behaviors, it was to anticipate their immediate desires: Would they be ordering the chicken or the salmon?” Now married and a father (the mind boggles just the tiniest bit), he finds himself enraptured with his home life—which is, well, just about as normal as you’d think. “My eight-year-old daughter, Ariane, does a terrific imitation of my wife threatening to choke a taxi driver,” he informs us. As for the wife in question, “it has been many months, maybe years, since anyone has seen [her] out of her regular attire of rash guard and spats. She’s a martial artist, a purple belt in Brazilian jiujitsu, and she trains full-time, seven days a week. Most of her efforts are spent practicing horrifying new ways to quickly, forcibly manipulate opponents’ feet, ankles, and knees in such ways as to permanently damage their tendons and ligaments.”

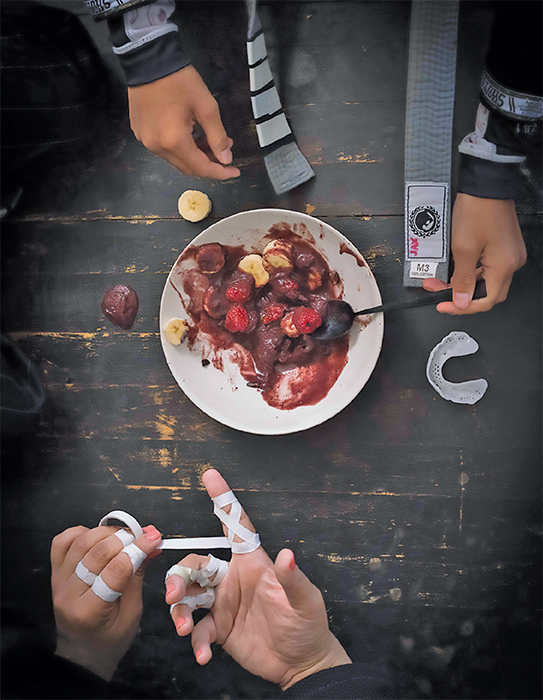

Which reminds me, naturally, of the Big Fucking Steak: mmm . . . muscle. Since Appetites is a book about what Bourdain likes to cook and eat at home, I broke it out on a recent family vacation. There was a huge crowd to feed, including four college-age water-polo players, so I threw eleven steaks on the grill—call it Even Bigger Fucking Steak—not a scrap of phony wagyu or Kobe among them. I followed Bourdain’s few suggestions, and he’s right about everything. Appetites, in addition to presenting an eclectic, expletive-laden portrait of one family’s fare, is also a really great cookbook. It covers everything from macaroni and cheese and deviled eggs to wild-boar ragout. There are recipes for things many of us eat all the time, like tuna salad and omelets, and they are good. There is a whole section on burgers. Korean army stew and various other Asian dishes that you can imagine trying out at home make appearances. In a quintessential Bourdain move, the recipe for an acai bowl is slotted into a category that I’m fairly certain exists in no other cookbook in the world: “Fight!” Its header is a gross-out masterpiece: “Brazilian jiujitsu is a thing in our house. Our lives—all our lives—revolve around training schedules; at any given time, there’s a heap of sodden, frequently blood-smeared gis (the two-piece garment, secured by a belt. . .) waiting outside the washer.”

It’s hard to imagine who else could get away with writing about bodily fluids and filthy laundry in a book about food preparation, even if it’s followed by an explanation of why the recipe it leads to is the perfect replenishment after a long training session. Then again, it’s hard to imagine who else could do many of the things Bourdain does. He’s a guy who can persuade President Obama to share a bowl of cheap noodles in Vietnam, the two of them charmingly hunched on little stools with cold beers at hand, and also announce in the “Hamburger Rules” section of this book that “if you’re putting mesclun or baby arugula on your burger . . . Guantánamo Bay would not be an unreasonable punishment.” This is precisely the kind of beyond-the-pale, willfully politically incorrect commentary that makes many people hate him, of course. He’s always been out to shock, and it can be hard to stomach. Despite an abiding interest in the world of restaurants and cooking, I could never bring myself to get more than a few pages into Bourdain’s best-selling memoir Kitchen Confidential, put off by its sheer—to use a word Bourdain might select—assholery.

When his tone is less menacing—when he isn’t using an infamous military prison as a throwaway punch line about salad greens—his barbs land with the kind of caustic humor that has made Bourdain a television star, even when he continues to indulge his instinct to provoke. A simple explanation of the best way to make bacon ends like this: “Hold cooked bacon on the interior pages of the newspaper of record, which have been proven to be among the most hygienic, bacteria-free surfaces you can find anywhere. Really. If you ever need to deliver a baby unexpectedly, just reach for a nearby New York Times Styles section. You can be pretty sure nobody has touched that.” (This made me flash back to his slightly queasy-making description of his daughter’s birth, “head corkscrewing out of the womb”—another first for a cookbook, I suspect.) His spaghetti alla Bottarga recipe features an alarmingly sappy little headnote: “After I fell in love with this dish on the Sardinian coast, I asked my father-in-law to show me how it’s done.” Incongruous images of Bourdain in happy kitchen concert with a jolly extended family floated through my head. Fortunately, I had only to turn the page and it was back to business with the wild-boar-ragout recipe: “As much as I’m enjoying having married into a large Italian family, I’m even more delighted about the Sardinian wing of the family on my father-in-law’s side. They live in a compound in the mountains, and they all carry knives—pretty much the picture of the perfect family to me.” What this has to do with the pasta recipe I have no idea—maybe these guys use the knives to kill the boars while running through the forest?—but it was a relief to know that no amount of togetherness can suppress Bourdain’s inner hooligan.

The night of the Even Bigger Fucking Steak, ultimately, was an all-Bourdain night. To go alongside all that meat, I tackled making a truly gigantic Caesar salad per his instructions (recipe note: “God does not want you to put chicken in your Caesar”). I made croutons by plunging cubes of white bread into a pan full of hot olive oil, garlic, and anchovies, and set them to drain on a sheet pan lined with newspaper (of which I had plenty, since there were no babies to deliver that afternoon). I whirled together the dressing ingredients, including raw egg yolks and more anchovies—as there should be—in the food processor. I grated Parmigiano-Reggiano and rough-chopped romaine. When it all came together, it was impressive and delicious. The consensus was that it was the best Caesar salad any of us had ever eaten (what is family for if not to show such bias toward your cooking?). It was also the first Caesar salad I’d ever made. Whether out of laziness or fear, I’d never bothered attempting the complicated dressing before, much less homemade croutons.

In Bourdain, I somewhat unexpectedly found my guide. With his words close by, I simply thought “Fuck it!” every time I was unsure about what I was doing, and forged ahead. If nothing else, I was pretty certain he wouldn’t mind if I blamed my failure on him; after all, he’s done a lot worse, even in this book (see: Guantánamo Bay). He led me to the promised land—or at least into uncharted territory. In Appetites, he admits he’s been going there himself, lately, and not just in the culinary sense. “The human heart was—and remains—a mystery to me,” he tells us, amid all the jiujitsu posturing and intentionally gruesome photos of animal parts. “But I’m learning. I have to.”

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).