They saw dead people. They heard them too. When summoned, dead people rang bells, wrote on slates, levitated tables. Sometimes their faces hovered in the air. The dead made this commotion for their parents, children, siblings, and friends at the behest of gifted individuals capable of readily communing with the world beyond. If the movement associated with this phenomenon, known as spiritualism—which was popular to varying degrees from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century—now appears a quaint relic of a benighted past, we should consider the vigorous currency of aura reading, crystal healing, and psychic consultations. These descendants of spiritualism testify to the ongoing human desire for an eternal force that operates outside the mortal limits of the body.

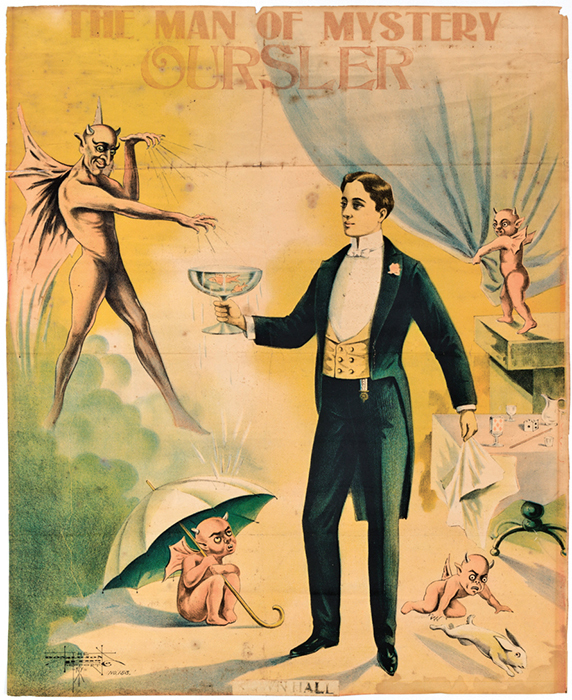

Of course, many of spiritualism’s practitioners—known as “mediums,” “psychics,” or “conjurers”—preyed on those in mourning, duping grief-stricken family members into believing they could communicate with lost loved ones. The especially cruel nature of the fraud provoked many skeptics and debunkers, including Charles Fulton Oursler (1893–1952), the grandfather of multimedia and installation artist Tony Oursler. An author of mystery and detective novels, Fulton Oursler (as he was known) waged battle alongside Harry Houdini against spiritualist practice, exposing its tricks and deceptions. Tony Oursler’s fascination with the eventful life of his grandfather—he was a polymath and agnostic, and his novel The Greatest Story Ever Told was adapted for the screen—is focused particularly on Fulton Oursler’s skeptical crusade, which is copiously evidenced by the 2,500 assorted photos, books, pamphlets, and objects the younger Oursler has collected over nearly twenty years. The portion of that archive that has been sequenced by the artist and published as Imponderable offers a dialectical view into a twilight world both distant and familiar, an archaic domain (there’s a printing plate for a late-eighteenth-century manual on how to cast spells believed to have been compiled by Moses) and one whose UFO and séance photos could be lifted from sci-fi and horror films. Oursler’s visual narrative animates the tension and mutual dependence between faith and science and, more crucially, between the longing for mystery and the need to understand.

The two images on the book’s first page encapsulate these paradoxes: A sepia-tinted photo of the Temple of the Sibyl in Tivoli, outside Rome, is juxtaposed with a schematic published in 1824 by Dr. Samuel Hibbert in a book investigating ghostly apparitions. His table purports to “measure the faintness or vividness of ideas, sensations, and emotions when one is experiencing a hallucination.” The sixth-century-BCE philosopher Heraclitus described sibyls as speaking with “frenzied mouth uttering things not to be laughed at.” So the female oracles and prophets who were worshipped at the temple in the photograph very likely behaved in ways that Dr. Hibbert sought to explain millennia later. His chart suggests that supernatural phenomena have physiological and psychological causes. While phantasms bequeathed by gods may turn out to be nothing more than the products of a high fever, the doctor’s precise-looking graph probably isn’t quite credible either by current medical standards. But solely in aesthetic terms, the decaying grandeur of the temple and its evocation of visionary rites make a more persuasive argument for the mythology that inspired its construction than Hibbert’s dull grid does for the scientific method.

With Imponderable—in addition to the book, Oursler released a film by this title in 2016, and his archive was recently the subject of a traveling museum show—Oursler engages a creative mode heralded by Hal Foster in his 2004 essay “An Archival Impulse” and recently showcased by the New Museum’s exhibition “The Keeper,” which treats materials collected and organized by artists as artworks. Archival artists, Foster writes, “seek to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present.” He cites the work of Thomas Hirschhorn, whose installations, or “monuments,” devoted to philosophers such as Spinoza and Gramsci gather sociology texts, pornography, and art reproductions. Hirschhorn’s expressed desire to “connect what cannot be connected” also describes Oursler’s intention—to thread together various histories (ancient, photographic, pop-cultural, occult, criminal, and familial) in order to breed multiple (and even contradictory) comprehensions.

As a book, Imponderable grants Oursler some control over his tale; for instance, materials are sequenced somewhat chronologically. At the museum exhibition, one wanders from vitrine to wall display, depending on what catches the eye. However viewed, the archive is experienced as immersive and integrative. Even as its materials range across time and continents, the cranial theme shared by Robert Fludd’s hand-drawn diagram of the mind, a decorated Tibetan skull, a production still from Georges Méliès’s La source enchantée featuring the disembodied head of an actress, and a selection of “thought photographs” that are allegedly mental images burned onto paper is readily apparent. Less so may be the connection between those images and, for example, a SoHo News cover shot of Kathy Boudin, a photo capturing the air around the muzzle of a discharged gun taken at four-millionths of a second, newspaper snaps of a nude man arrested at a convenience store, a postcard of an “image of Christ” as discerned in a rock formation in Minnesota, and a photo of “Monkey Trial” defendant John Scopes. One’s progress through the pages slows to accommodate microeddies of meaning and then speeds up as connections jump like electrical charges, from Wilhelm Reich to Houdini, from dream drawings by Federico Fellini to the drawings of Augustin Lesage, an early-twentieth-century coal miner whose pen was directed by spirit voices. Typically, the structure of an archive connotes an orderly inclusiveness, but voraciousness marks Oursler’s; he’s creating an inhabitable atmosphere (screenings of the film version of the show even offer sensory effects such as smells and vibrations under the seats) that mimics the mind’s buzzing confusion—its combinations, collisions, revisions, and intuitive feats. His archive’s coherence is its persuasive performance of incoherence.

But Oursler’s tale of spiritualism—its occult antecedents, powerful presence in American and Victorian culture, and the controversy its paranormal claims generated—is straightforward enough. Grounded in his grandfather’s rationalist quest, Oursler’s image trove reveals how various charlatans attempted to use the products of science (principally photography) to validate the supposed mystical truth of their histrionics. The faked images of spirit photography, in which the ghost-white bodies of the deceased loom in darkened rooms, or billows of ectoplasm pour from a medium’s mouth, were deployed as conclusive evidence by spiritualism’s true believers. No less than the creator of the deductively inclined Sherlock Holmes was taken in by this gimmickry; Oursler includes the images of sprites that Arthur Conan Doyle professed to be real in his book The Coming of the Fairies. Spirit photographers were intrepid innovators—two Scottish brothers devised “a new kind of spirit writing” by wrapping photographic plates in black paper on which the dead then supposedly scribbled. These “skotographs” were delicately beautiful and anticipated the visual poetry of asemic writing—still, that didn’t prevent the brothers’ arrest when undercover police discovered that the images were manipulated. Of course, debunkers employed the same technology to unmask frauds. A Chicago medium who made use of a “spirit horn,” through which she claimed the Native American chief Black Hawk whispered, was exposed when a journalist’s camera caught her in the darkened room with the horn to her lips. Technology could abet both deception and detection.

The depth and scholarly verve of this archive suggest that Oursler recognizes the stakes in this battle over truth. By concluding with several pages devoted to UFO sightings, he connects current contestation over outlandish government conspiracy theories to the passions once generated over talking ghosts. Still, he clearly delights in the entertainment value found in the cage matches that pitted skeptics against believers. A luridly illustrated 1920s poster has it both ways, as it invites the audience to witness “FAKE MEDIUMS EXPOSED” and “See How Spook Crooks Fool Their Victims” while “solemnly” warning that “during seances almost anything is liable to happen.” The hair-raising brew of grief, fraud, the uncanny, and the cops proved irresistible to showbiz. Houdini’s much-celebrated debunking efforts were both grandiose and logically purposeful. To prove that it was medium Margery Crandon, and not a ghost, ringing the bell during her séances, Houdini built a cabinet with “extra hasps and staples” to contain all but her head. That the box looked more like a torture device from his escape act than an instrument of scientific experimentation was no accident. Spiritualists took a revenge of sorts, if only on Houdini’s wife, by relaying messages from her husband after his death in 1926.

The archive—diversely sourced but deeply interconnected, provocative but hardly polemical—makes it difficult to know what Oursler thinks about any of its particulars or even the big eschatological questions; after all, the title of the project is Imponderable. His inclusion of Kirlian photos—images that appear to document the “coronal energies” that emanate from objects—done by his friend David Bowie might indicate an actual belief in auras, admiration for the singer, or simply an aesthetic attraction to the pictures. At least half the items in the volume could be separated from their archival context and still warrant attention as artworks: The photo depicting several bare-chested young men in various states of slack repose under the ministrations of a hypnotist brings to mind Diane Arbus’s portrayals of patients in mental institutions; another in which a medium’s hands float against darkness, poised as if preparing to crawl toward the viewer, recalls Albrecht Dürer’s Hand of God the Father; a “thought photograph” from 1950 could easily be mistaken for one of Alberto Burri’s “Combustioni plastiche” (Plastic Combustions). Perhaps there is no portal between the mortal world and the spiritual realm, if such a locale even exists. Oursler’s archive merely invites us to brood over the myriad ways humans have thought and acted on their wish for, or denial of, the supernatural. But experience within this prodigious assemblage of scientific documents, posters, pop-culture curiosities, obscure engravings, newspaper ads, doctored photos, and so much more proves a different permeability—one between high and low culture, between the found and forgotten, and between the art of fraud and the truth of art.

Albert Mobilio’s book of short fiction Games and Stunts was recently published by Black Square Editions.