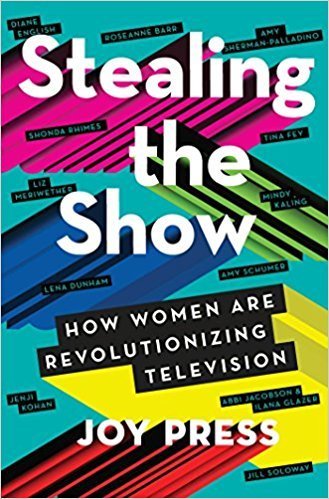

One side effect of the Trump presidency so far—among the mildest and yet, for book reviewers, still very noticeable—has been its distortion of a popular nonfiction genre that wasn’t hurting anyone. Since late 2016, a whole slew of sunny, triumphalist works about the social, political, and cultural progress being made in one corner or another have been forced to add awkward, doomy turns to their introductions and conclusions, the beginnings and ends of their chapters. Thus Joy Press’s Stealing the Show: How Women Are Revolutionizing Television, whose prevailing mood matches its effervescent title, must now frame its reported profiles of contemporary TV titans and disrupters like Shonda Rhimes, Tina Fey, and Jill Soloway with caveats about zigzags in the moral universe’s arc. “By reflecting the reality of women’s lives, the television creators in this book arguably helped provoke the current political backlash,” she suggests, in an effort to turn the involuntary plot twist of Hillary Clinton’s loss back on itself. “That means they could play a prominent role inspiring the resistance.” (The offbeat blend of victim-blaming and aggrandizement on display in these two lines offers an exemplary summary of what women who work in television have to contend with even from their friends and fans.)

Since the question of real-world political change has intruded on Press’s subject area, she may be feeling a new discomfort with the language of “revolution.” In theory, if you can have a war on Christmas, then why not a revolution in TV? But would that require just changing television, or using television to change the world? Even the first requirement seems slippery. There is now such a wide variety of successful television made by and about women that it can’t easily be treated as a genre unto itself. To do so has at last, and only very recently, begun to feel as hopeless and absurd as it ought to—like trying to write about what distinguishes books by women from those by anybody else. And while there’s plenty of inventiveness in current television, it’s hard to claim that women invent differently in terms of form or tone.

What Press focuses on here is what gets the most attention elsewhere, too: how women represent women, their bodies and relationships, their lives at home and work; what stories are told, and what is seen now that might once have remained hidden. It makes sense for her to start her series of case studies with Diane English’s Murphy Brown, the vision of upper-middle-class-liberal feminism that became an ostentatious flash point in the culture wars of the early 1990s, and with Murphy’s earthier counterpart, Roseanne Barr, whose eponymous show broke many of the rules for how women could appear on TV and how much power they could wield offscreen. Those rules, unfortunately, have tended to need a lot of rebreaking.

That’s the problem with concentrating on representation. You quickly get stuck chronicling the same fights, as women writing women are congratulated over and over for the same small victories. Things that might—should—seem obvious must be established and defended repeatedly on TV: Women can be funny; women can be competent; women can screw up; women can have friends; women can work and raise kids at the same time (as most have to); their bodies vary and so do their experiences, but the former need not fully determine the latter; they age and this may not be a catastrophe; life is full of other catastrophes, but not all of them are the awful fate of womanhood; many things interest women besides love and family, including work, art, politics; given these interests and ambitions, there’s no reason a woman, or, say, a large group of women of different ages, races, and body types, can’t carry a TV show. Those who make television are highly aware of its usual constraints, even when operating outside them, and their audience always knows where the guardrails are: If a character gets pregnant by mistake, we still brace for the deus ex machina miscarriage that’ll take abortion off the menu, and so on.

Few people could be more vulnerable to the overcongratulation syndrome than pop-culture critics of the 2000s, most of whom will have had to cultivate a certain myopia in order to cope with and justify the expansion of their profession. After several years of running TV coverage as an editor at the Los Angeles Times, and, before that, as chief TV critic for the Village Voice, Joy Press is understandably relieved and excited about the proliferation of talented women in more visible positions of power, and she can’t help grading some of the shows they make on a curve. (The rise of the “showrunner” also plays its part in this hyperenthusiasm, as the recent history of television has offered writers a new and attractive image of the possibilities: “Writing tends to attract socially awkward introverts with shoddy math skills,” Press notes, but in the twenty-first century, all of a sudden, “the nerds were managing multimillion-dollar productions.”) If the TV “revolution” here can start to feel a bit like an endless spin around a goldfish bowl, that’s not Press’s fault, nor her subjects’. From English and Barr, Press moves on past Amy Sherman-Palladino’s Gilmore Girls to Shonda Rhimes’s and Jenji Kohan’s dramas, Tina Fey’s and Mindy Kaling’s sitcoms, and the cheerily progressive filth of Amy Schumer and Broad City—a show whose signal achievement is its evocation of a universe in which Chloe likes Olivia and neither is ever punished for their antics—before closing with Jill Soloway’s Transparent. Much of the book hovers in an uneasy territory between bigging up every teeny advance in how women appear on TV and anxiously logging the frustrations of those who make these shows.

Press reminds us that breakthroughs usually happen via an economic shift in the industry rather than a cultural one (which is partly why TV-land has often lagged so far behind real life), as when streaming services trying to compete with stumbling network giants have an incentive to offer creators better, freer terms, and shoestring web series begin attracting investment. Since there are few big fat safe bets left, people are more willing to gamble on supposedly niche interests that often turn out not to be so niche after all. Then there’s the very occasional appearance of a Shonda Rhimes, who, through her ingenuity and massive appeal, redefined what a safe bet could be.

Not everyone makes it look that easy. A few shows made by women in recent years have been metafictional explorations of what it’s like for women who make television. As well as Fey’s 30 Rock, there’s UnReal, Marti Noxon and Sarah Gertrude Shapiro’s soapily plotted romp behind the scenes of the fictional show Everlasting, a stand-in for The Bachelor, where Shapiro spent a few years as a producer. It’s a portrait of women at work, putting ten times the psychic and intellectual energy into their jobs as into their male love interests, who come and go more or less at random (the women’s matching wrist tattoos inscribe “Money. Dick. Power.” as their order of priorities, like a sick little twist on a Didionish professional woman’s packing list). The catch is that their jobs involve reinforcing the most retrograde sexual dynamics imaginable. One of UnReal’s animating questions is whether success for a woman in such an industry requires a full-blown personality disorder.

A dispiriting episode of Pamela Adlon’s semiautobiographical Better Things offers another, less-heightened glimpse of the unwinnable game being played by women off camera. In one sequence, two guys who are casting a pilot for their new show tell their female producer that they passionately want the lead to go to a fortysomething actress (Adlon’s character) who everybody understands is a has-been. The young woman patiently tries to dissuade the dudes; never-theless, they persist. No one else will do. In a meeting with the skeptical studio honcho, the woman has to protect the guys and their show even if it means sacrificing her own credibility—the older actress is funny, she insists, and that’s what matters most. The honcho agrees, but soon after calls to tell them he’s signed someone less milfy after all—a huge movie star who is TV-lead hot and funny. This is an economical demonstration of the elaborate structure of disincentives that keeps women from trying to make any kind of unusual choice, still less help one another out. Whatever the producer does, she’s screwed, but it’s clear that the closest thing to a safe option would have been to out-macho the men and insist on casting a teen ingenue. Instead the boys have managed to keep their creative integrity, look open-minded, and end up with a far better result than they could have gotten by asking for it. Without even having to try, they’ve dumped the risk on her and kept all the rewards.

It’s difficult to tell from Press’s book just how naughty or nice you have to be to get something on the air without too much debilitating compromise. There’s a breathlessness in the report that Rhimes and Soloway have provided childcare for their staff that makes clear how rare that must be. Both Kohan and Rhimes are said to have a “no assholes” policy in hiring. And yet: Consider the asshole. Who exactly is s/he, in the context of television? It’s evident that Roseanne was eventually derailed in part by the same attitude problem that made it possible in the first place, let alone such a giant success. Had Barr known where the line was, it might well have stayed in place. Even Jill Soloway, whose image as a nurturing mama bear is now firmly entrenched, was flagged as “difficult” in the decades they worked on other people’s shows while struggling to get their own projects made. (Soloway came out as gender nonbinary in May, and prefers the singular form of the pronoun they.)

There are obvious reasons why Press chooses Soloway’s Transparent as her culminating case study. An episodic family drama in which everybody disappoints and no one will grow up may not feel new, exactly. But the way in which fluid sexuality and gender can appear at every turn and in every stage of life, as they do in the actual world, has the shock of the familiar but rarely shown. The central challenge for Transparent is the same one that dogs other productions here: the tiresome battle over how much lived reality can be included. The responsibility of constantly being treated as a representative for women, or for LGBTQ people, in general, is an onerous one. Too often, it thwarts efforts to talk about anything else, to tell a different story or even just have conversations that in real life might be a starting point rather than the goal. This doesn’t have to look revolutionary—sometimes it’s simply about allowing funny or insightful material into the mainstream, like the everyday interactions between black women that Issa Rae’s HBO comedy Insecure makes visible.

Transparent, though it’s a study in the selfish brattiness and inadequacy of almost all its characters, has to be vigilant about not seeming to reinforce hateful stereotypes. Because it is celebrated (perhaps too much) for showing trans life in a new way, it owes its trans viewers a debt that it’s always in danger of not paying. Still, some episodes explore the gray areas in the conflict between radical feminists and trans women, while an encounter with a trans man makes use of Gaby Hoffmann’s flair for playing the kind of asshole who transcends considerations of gender. Jeffrey Tambor’s character, Maura, gets schooled for her pretransition misogyny by an Eileen Myles–alike, and we also see Maura embarrass herself by presuming that some Latina trans women she meets must be sex workers. For once, it’s as if the burden of representation can be shrugged off, opening up more ambiguous territory where both defensiveness and defiance are beside the point.

But only “as if.” Trace Lysette’s account of being assaulted on set by Tambor was one of the bleaker #metoo testimonies, not least because of her fear, evident in every line, that by saying anything at all she might be threatening the existence of one of the only shows with major, recurring parts for trans women. And Press mentions the negative reactions that greeted some of Transparent’s writing, such as the episode with the trans man not macho enough to please Gaby Hoffmann’s Ali. Rhys Ernst, a trans man and producer on Transparent, realized only after it aired that they may have gone too fast for their audience: “What we missed was that this was the first time in history that a trans man had ever been represented on TV played by a trans man.” They’d been “trying to jump to a future level of messiness,” failing to notice that “everybody else felt they needed positive affirmation first.”

Lena Dunham’s Girls actually contained many small, intriguing moments of such ambiguity, but like Roseanne Barr, Dunham, at least online and in the press, had an asshole problem. It makes sense that she was able to perform the trick of seeing things her way and having her conversation as if the usual limits and accusations and shocks and horrors did not apply. Unfortunately, it often takes enormous material and social privilege to shut out all that noise—privilege that can sometimes distort the work if it’s not intended to be the main subject of discussion, as it was in Dunham’s far more consistent film Tiny Furniture (2010). For anyone not bred for this sort of oblivious overconfidence, it’s hard to construct a playground in which to experiment freely.

Press notes that Soloway envied Dunham the opportunity, having slogged away in TV for decades before getting their own. Every profile of Soloway emphasizes the maternal anti-machismo in their working methods—they preside over a collaborative, asshole-less, intimately oversharing writers’ room in which different identities are represented and hardened TV veterans are in the minority. Press’s account is no exception, and, not for the first time, I began to bristle at the vaguely essentialist overtones of some of these descriptions: People seem to be bursting into tears on every other page; Soloway leads “from the pussy, as she would say”; the goddess must be thanked for each success.

Soloway seems now to share my doubts about this sort of thing—Press mentions that their way of talking about gender shifted drastically in the time between interviews for the book. But Press’s treatment of the bubble-bath scene in “Flicky-Flicky Thump-Thump” also made me question my reaction to some of the pointed femminess. The scene shows Maura, who’s been living in a sexless, half-awkward, half-comforting arrangement with her ex-wife, Shelly (Judith Light), leaning down from the edge of the bathtub to bring Shelly to orgasm. A memorable scene that should have felt like a mundane one, it dodges a lot of pitfalls. It has a very particular and also universal sadness: sad because Maura knows that Shelly, at some level, still wishes Maura could be the husband she once was; sad in its sense that intimacy between people so often outlives their ability to make each other happy; sad in that knowing what one wants and how to get it doesn’t grow any easier with age. It doesn’t read as sad or strange in other ways it could have. To the extent that the shows I watched growing up acknowledged interactions between trans and cis people, they were usually portrayed as heartrending, if not outright damaging to all concerned. And the question of an older woman wanting love and sex at all tended to be avoided or mocked, her desires treated as unnatural and bound to provoke pity or distaste.

To read the interviews with the makers of the show is to be struck by how much ingenuity and how much Sturm und Drang was required to make the scene what it is. From Press we learn that, before filming, Soloway held hands with Light and Tambor and prayed: “We ask that this be received in the way we are giving it.” They explained to Light that she was “part of a revolution,” that they were “showing things that no one has ever seen before, and you are going to get to share with the entire world what everybody is afraid to see, which is Mom having pleasure.” Reading this, Soloway’s talk of the “female gaze” grew more resonant for me—not the essentialist concept it could be misinterpreted as, but simply a stripping away of the conventions that have constricted the portrayal of women’s experiences on every scale. It also seemed yet another puncturing of Press’s bouncy tone. If this is what has to count as revolution, it’s no surprise that it’s still so rare to see a show that dismantles the guardrails for the entirety of its run.

Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag is one remarkable exception. The treatment of both sex and feminism in her show—from the anal scene that begins it to the women’s silent retreat held near enough to a male misogynists’ recovery group to hear their primal screams of rage against “sluts” and “bitches”—becomes a decoy for an exploration of guilt and grief and resentment that chooses its own constraints with only artistic considerations in mind. You can tell that this material has been allowed to develop outside the confines of television, onstage, where Waller-Bridge performed versions of it hundreds of times. This may confirm the promise of more good things to come from TV’s changing economic model. Shaping your work first in stage shows or a web series might offer some protection against the effects of having to fight your way up within the cable or network hierarchy, allowing for the kind of creative freedom Louis C.K. sought with Horace and Pete, despite already having a license on his FX show Louie that few women showrunners so far have even dreamt of. Waller-Bridge has said that she’d originally ended the stage version of Fleabag by sexually assaulting a rodent. (“Darling, it’s so layered. You don’t need the guinea pig,” her mother tactfully suggested after one performance.) The TV show is still garnished with absurdist touches: While the guinea pig is spared in this final iteration, it remains present as the excuse for a painfully inspired joke about how “people make mistakes.”

Waller-Bridge provides an encouraging example. Yet the idea that women should fund their own experiments before getting them on air may only reinforce the Dunham conundrum—or perhaps implies giving up on TV qua TV. My real hope is that the slow power shift Press documents will eventually make possible a creative transformation that fully justifies her optimism. In the future, more women (and others) who share the aim director John Waters once espoused, to cram the most subversive ideas into the most mainstream product, may at last feel free to get the job done.

Lidija Haas is a New Books columnist for Harper’s Magazine and a contributing editor of Bookforum.