Call it the travelogue paradox: In books that purport to be about the perils and pleasures of life on the road, travel itself is typically no more than pretext. The real story being told has to with the self and its tentative steps into some great unknown. A travelogue is ultimately a coming-of-age story with its thumb stuck out.

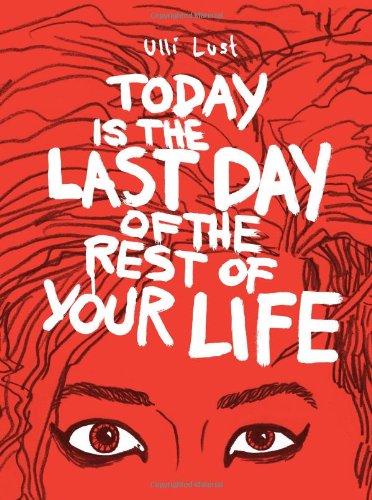

Ulli Lust’s graphic memoir of the time she spent hitchhiking and otherwise relying on the kindness of strangers in Austria and Italy makes little pretense of caring about the locales. When Ulli, a punked-out and disaffected seventeen-year-old from a middle-class Viennese family, sets off on her trip, she doesn’t have a particular destination in mind. What she wants is to escape the boredom of bourgeois Austrian life and do as she pleases, “not what someone is telling [her] to do.” And so, in the winter of 1984, she takes off for Italy with a girl named Edi, a nymphomaniac with no intuition or discernment.

Lacking the proper documents, the girls make their way to Italy surreptitiously. Their situation is precarious: “Two 17-year-old girls hitchhiking to Italy—a country which I only knew from book and movies—with just a sleeping bag—a blanket, no spare clothes, no money, no papers.”

And they love it: “We felt like global explorers!!!” Ulli writes in her travel diary. Her early experiences, rendered in shades of black and pale green, include bumming rides from strangers, hanging around Rome’s Spanish Steps with fellow punks (and sleeping in the park above them), panhandling (the Romans, she finds, are quite generous, because “the contrast between rich and poor is so huge…it’s considered common courtesy to give an alm”), and seeing an ecstatic Clash concert. This is all new for Ulli, and it seems like she is on the brink of self-discovery: Midway through her travels she tells a fellow wanderer, “For the longest time I’ve felt that everything I know I know only from books. Now I’m finally experiencing something myself!”

Of course, danger still lurks, and Ulli becomes something of a latter-day Little Red Riding Hood besieged by wolves, particularly after she leaves Rome for Italy’s less-traveled regions. On almost every page, she is set upon by men who tell her she has beautiful eyes and expect sex in return for the unwanted compliment. At first, Ulli gives in: although she takes little pleasure in sex, she seems to think of it as a necessary component of her rebellious new life. But once she starts to rebuff these advances, she recognizes her vulnerability as a young woman on her own. Separated from her friends as they make their way to Palermo, Ulli tries to make herself less visible to men, washing off her makeup and hunching over in an attempt to conceal her breasts. But “stomp[ing her] feet like a man” and refusing to look men in the eye or return their greetings (“every look,” Ulli surmises, “is an invitation”) fail to protect her. She is raped. What follows is a turn of events that culminates in Ulli romancing her rapist.

This is a shocking conclusion, and one that could easily have sparked a moment of reckoning, or at least a more thorough consideration of the reality of being a young woman alone in the world. But Last Day is marked by its conspicuous lack of hindsight. Composed fifteen years after the fact—the original German edition was published in 2009—Lust makes no effort to bring her later experiences to bear on the narrative, and the story is presented without any real attempt to explore the issues it raises. While there is something refreshing about a memoir that takes adventure at face value, the result is mostly confounding. Last Day sometimes seems like a version of Groundhog Day without a moral: experiences are repeated, the same mistakes are made over and over again, men’s forceful come-ons never cease, and nothing is conclusively learned. When Ulli does return home to Vienna, she never even stops to think about who she has become during her Italian sojourn.

Setting out on her trip, Ulli does not quite know who she is. That’s not a problem: the point of the journey, after all, is to find out. What is problematic is that we never know whether she ultimately learns anything. By framing her memoir this way, the author might well be suggesting that the future must remain murky, a journey rather than a destination. Still, by shirking on both the Bildung and the travel, this travelogue feels somehow incomplete, like getting to a place and finding its major attractions closed.

Yevgeniya Traps lives in Brooklyn. She teaches at NYU Gallatin and at Barnard.