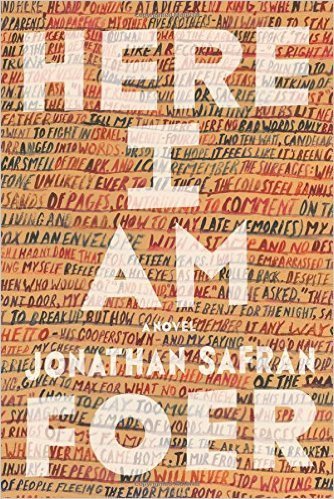

Jonathan Safran Foer is the Louis C.K. of the Jews. “I feel like America is the world’s worst girlfriend,” Louis says in one of his routines. “When somebody hurts America, she remembers it forever. But if she does anything bad, it’s like, ‘What? I didn’t do anything.’” Foer, too, likens romance to world events. In his new novel, Here I Am, he compares the dissolution of a marriage to a devastating earthquake in Israel. But where Louis plays this type of hyperbole for laughs, we are never quite sure how to react to Foer’s histrionics—he’s both the teller of the joke and the world’s worst girlfriend.

An earthquake is an act of God; the end of the marriage, an act of stupidity. Jacob, the protagonist of Here I Am, has been secretly sexting with a lady who shall remain unnamed. To sext her, he uses a burner phone. Jacob is fronting. He longs to be more like his hunk of a cousin, Tamir, an Israeli businessman who represents the epitome of Jewish masculinity: “What were Israelis? They were [Jacob’s] more aggressive, more obnoxious, more crazed, more hairy, more muscular brothers … more brave, more beautiful, more piggish and delusional, less self-conscious, more reckless, more themselves.” Jacob, on the other hand, is the kind of guy who locks himself in the bathroom nightly to self-administer a suppository, treating an unspecified ailment we begin to feel resides more in his head than his ass.

There’s a lot going on in this novel of nearly 600 pages. Often, a single theme, such as the terror that can accompany aging, is invoked in several subplots: A very old Holocaust survivor whose family wants to move him into a home for the elderly refuses this decampment by hanging himself. An incontinent dog refuses to die of natural causes, obliging his owners to decide the date of his execution. A man just past forty and feeling lonely in his marriage flirts with the idea of fucking someone else and with the idea of joining the Israeli Defense Forces (in the wake of the aforementioned earthquake, Israel’s Prime Minister issues a call for men and women of the diaspora to enlist), in the end doing neither.

You have the sense that Foer has suffered to write this book—suffered in life more than in the making of art; for the most part, the writing in this book is agreeably fresh and fast and unmannered—and call me a sadist, but the suffering has improved his prose. He’s no longer so worried about losing our attention for one second, so he spins fewer plates. What he’s lost in precociousness he’s gained in a certain self-aware world weariness. It’s as if he’s eavesdropped on all the cocktail party chatter—what has he been doing all this time? Does he know how insufferable he can be?—and beaten us to the punch: The book is an exercise in self-punishment, and spilling his guts, he finds, is both cathartic and wincingly funny. Witness the first-ever argument in Jacob and Julia’s marriage, which happens after they smoke pot and decide to get really real with each other:

“We were in the apartment the other day. It was Wednesday, maybe? And I made breakfast for you. Remember? The goat cheese frittata. … I made it because I wanted to take care of you.”

“I felt that,” she said, moving her hand up his thigh, making him hard.

“And I made it look really nice on the plate. That little salad beside it.”

“Like a restaurant,” she said, taking his cock in her hand.

“And after your first bite—”

“Yes?”

“There’s a reason people withhold.”

“We’re not people.”

“OK. Well, after your first bite, instead of thanking me, or saying it was delicious, you asked me if I’d salted it.”

It’s a ridiculous scene, a send-up of first-world problems that reveals a lot about this couple’s dynamic even as it signals that Foer, like Philip Roth savaging Sophie in Portnoy’s Complaint, is in on the joke. Is it annoying or is it interesting? Interestingly, it’s both.

Hanging out in the mind of Foer is generally an entertaining, if exhausting, experience. He gives good detail—“the albumin archipelago on the salmon”; “the eeriness of frozen breast milk … how Sam’s hands lurched upward, like those of his falling-monkey ancestors, whenever he was placed on his back.” Then he offers a great deal of commentary and exegesis on it all. This is perhaps no surprise in a book that features one Dr. Silvers, a psychologist whose sessions with Jacob seem to encourage rather than allay a tendency toward verbalized introspection and self-analysis and neurosis.

A reader would be forgiven for wondering what Jacob is so neurotic about. He has a beautiful wife, Julia, three smart and delightful children, and an elegant house in a tony neighborhood of DC. An accomplished and celebrated writer—“You realize I won a National Jewish Book Award at the age of twenty-four?” he asks Max, his middle son, in an attempt to get his attention—he now works on a TV show with a viewership of approximately 4 million. His parents, Irv and Deborah, are active, loving, and doting grandparents.

But Jacob's life isn't as perfect as it seems. The good-cop/bad-cop roles he and Julia have assumed in regard to that odious gerund “parenting” have left his wife feeling like the Enforcer, and a mother to four boys, not three. Jacob is the cool dad who buys the kids a dog on a whim. Julia is more uptight. And Julia is beautiful—you get the sense Jacob always feared she was out of his league—and also cold, spoiled, and disciplined. Jacob does not adhere to that old adage, show me a beautiful woman and I’ll show you a man who’s tired of making love to her; show Jacob his own beautiful wife and he will pine away in silence on that point, while yammering on about any- and everything else.

For these highly sensitive, literate, urbane yuppies, the real violence is not so much the furtive skirmish of texted desire for another, or the raised voices in the fight occasioned by the discovery of the secret phone, or even Jacob’s hurling the offending instrument of betrayal through a window, but the airing of the thought that they may not be together forever. That, once spoken, can’t be retracted. This couple is linguistic. (Jacob reveals, late in the novel and much to his wife’s surprise, that he knows sign language.) Love of talking is what brought them together, and it’s what they’ve lost little by little: the ability to speak to each other, to say what’s actually in their hearts and on their high-functioning minds. They used to have intense, lofty conversations. Now the quotidian has crept in, and it’s the quotidian they can’t handle. Their style of parenting is deliberate and hyper-attuned—not so much helicopter as drone. On special occasions, the children are permitted a sugary carbonated drink, but it isn’t a Coke, it’s an Italian soda.

Here I Am is a long document about failure and the fear of it. Jacob fails to be a man in the brawny, GI Yakov sense, fails to stay married, fails to soften the politics of his bombastic neo-con father, and all with such earnestness. Cerebral, delicate, anemic; thirsty for applause, plaudits, cuddles, pats on the back, guffaws (his hyperactive patter goes on so long his family laughs to change the subject); sexually frustrated (and how) and self-aware to the point of paralysis—omg this guy! He’s pretty needy. In some ways, he gets what he wants. He knows how to inspire sympathy, and to use that sympathy as a path into women’s hearts. We see this when Jacob, newly separated and shopping at IKEA, runs into Maggie Silliman, the mother of his son Sam’s preschool friend. Maggie is under the impression that Jacob went off to war, when in truth Jacob only got as far as MacArthur Airport in Islip, Long Island. Jacob does not correct her—but wracked with guilt about the fib, he does not sleep with her either.

Foer is too much of a figure in the culture to hide behind Harold Bloom’s injunction to read fictional characters as an entity entirely independent from their creators. (Jacob confesses to having plagiarized Bloom for a college paper.) Foer, dubbed a wunderkind when he published Everything Is Illuminated in 2002 at the age of twenty-five, came of age as a writer in a particularly self-conscious way. His ascent was a hot topic among a segment of literary New York that keeps track of things like book and movie deals, house prices, hot wives, prizes, and whether a writer has become successful enough, materially and in the cultural-relevance sense of it, to woo movie stars. To the NPR set, in particular the baby-boomer generation of Jews, Foer is a dazzling adorable boychik. To a guarded, jaded, essentially envious species (i.e. other writers), Foer is embarrassing for a number of reasons. He goes straight for the heartstrings, which he plays like Itzhak Perlman—cf. the cutie-pie narrator of Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, a nine-year-old who loses his dad on the morning of 9/11.

Here I Am has its own darling youngsters and moments of heartache, but what some would call treacly I will call sincere. Foer, who has written a book about his vegetarianism, really doesn’t want you to eat animals. He thinks with intensity and nuance about subjects that are hard because they are big, well-trod, and/or obvious—family, masculinity, sexuality, the Holocaust. It may be overmuch, but it isn’t timid. It may have taken an age to produce—it’s his first novel in a decade, and parts of it definitely waft eau de musty desk drawer, while others feel to have been written very quickly and recently; but this is a mishmash I don’t mind. “Here I am” (“Hineni” in the Hebrew), says Abraham to God, when God calls on him to sacrifice his only son. “Here I am,” Abraham says to Isaac when the boy calls, “My father!,” asking innocently where is the animal they are planning to slaughter. “Here I am,” Abraham says a third time, to the angel who intercedes to spare Isaac—it was a false alarm. There are less epochal false alarms in Foer’s ragged story about betrayal and love. This book is big and awkward, not honed and refined, but the mess feels true.

Gemma Sieff is an editor at Bookforum.