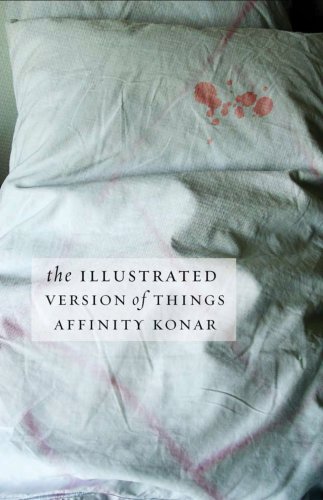

The plucky unnamed street urchin who narrates Affinity Konar’s vivid and disturbing first novel, The Illustrated Version of Things, is seemingly sprung from a Carson McCullers novel. A high school version of Jodie Foster’s knock-kneed nymph in Taxi Driver, she possesses an almost beatific naïveté that is decidedly Dargeresque, despite being a survivor of the streets and the foster-care system and recently released from a mental hospital.

Konar’s novel is set in the realms of the wacky if not the unreal; it’s a weirdo adventure story in which the narrator is ostensibly searching for her mother, who has been mysteriously incarcerated. The book’s other characters, who, it seems, exist to abet her search or to act as alternate family members, are gothic grotesques—her mother’s former pimp; the narrator’s biological father, a male nurse who makes vitamins; a pedophile who wears his mother’s hair as a wig; a bag lady the narrator directs to act like her brother. Then there is her actual brother, alternately named Miguel and Moses, who has been placed with a new foster family during the narrator’s time in the mental ward. He acts as a saner and skeptical Sancho Panza to her Don Quixote. Throughout the novel, the girl misfit gets into a series of violent altercations out of boredom or some unexplained impulse. Eventually, she gets herself locked up in a women’s prison in order to meet her imprisoned mother, who, the reader discovers, has escaped or been released and has now become a magician’s assistant, in a scene that resembles a kiddie version of Mulholland Drive’s Club Silencio.

The Illustrated Version of Things calls to mind Deborah Levy’s marvelously lunatic Billy and Girl, although Levy’s tale—also about a brother and sister hoping to find their birth mother—is a tightly choreographed series of explosions, whereas Konar’s is a sprawling misadventure. One also thinks of J. T. Leroy’s truck-stop victim lit and Stanley Elkin’s sick and twisted carnivalesque universe. There is a madness and violence to Konar’s narrator, and this emerges through the language, unfamiliar and strange, the pace building at times to a glorious insanity in passages surreal and associative, seemingly written on an all-night hallucinogen bender. When the narrator apologizes to a blind foster child, nicknamed Mustache, for stabbing him with her fork, it occurs to her “that showing him my regret might be better, so I push my most contrite and athletic drumstick in his direction. He still fails to accept my apology, and this is when I realize that nothing I could do would ever be enough. I could bite my tongue for him. I could light candles, scatter seed, bring him the head of foam from some dark beer. Walk on hot clocks. Wear mosquitoes in my hair. I could shed three drops of blood from my eyes. Hail a taxi. Wave palm fronds. And Mustache would just sit there in his barbeque stains. He would not be moved.”

If there is a larger theme in Konar’s work—a meditation on misfits and vagabonds, for instance—it is hidden by her pyrotechnic style. It is difficult to tell whether she views her characters with empathy or as tragedies or merely as wacky objects. But the novel is worth reading simply for the way Konar perverts and pummels her sentences, for the exuberance and eccentricity of her language, its lurid energy and rhythms.

Kate Zambreno's first novel, O Fallen Angel, will be published in Spring 2010 by Chiasmus Press.